As Howard Zinn describes in A People’s History of the United States, the most destructive period of civil violence in U.S. history occurred during four days of rioting in July 1863. Zinn writes, “The draft riots were complex — anti-Black, anti-rich, anti-Republican.” This activity focuses especially on the conflict between recently arrived Irish immigrants and Black people.

One of the critical “habits of the mind” that students should develop throughout a U.S. history course is to respond to social phenomena with “why” questions. They should begin from a premise that events have explanations, that people don’t, for example, kill each other simply because they speak different languages, attend different churches, or have different skin colors.

This activity takes the outrages of the 1863 riots as its starting point, and asks students to piece together clues that help account for this sudden explosion of rage. It’s important to note that making explanations is different than making excuses. Here, we’re asking students to try to understand the horrors committed, not to rationalize them.

Note: It’s best to do this activity before students have read about the draft riots in chapter 10 of A People’s History of the United States, excerpted below.

. . . the Conscription Act of 1863 provided that the rich could avoid military service: they could pay $300 or buy a substitute. In the summer of 1863, a ‘Song of the Conscripts’ was circulated by the thousands in New York and other cities. One stanza:

We’re coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand more

We leave our homes and firesides with bleeding hearts and sore

Since poverty has been our crime, we bow to thy decree;

We are the poor and have no wealth to purchase liberty.

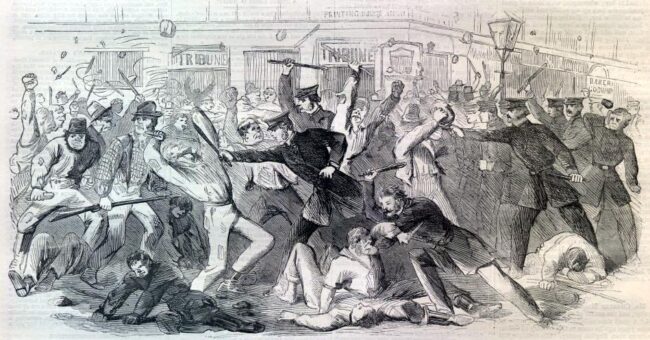

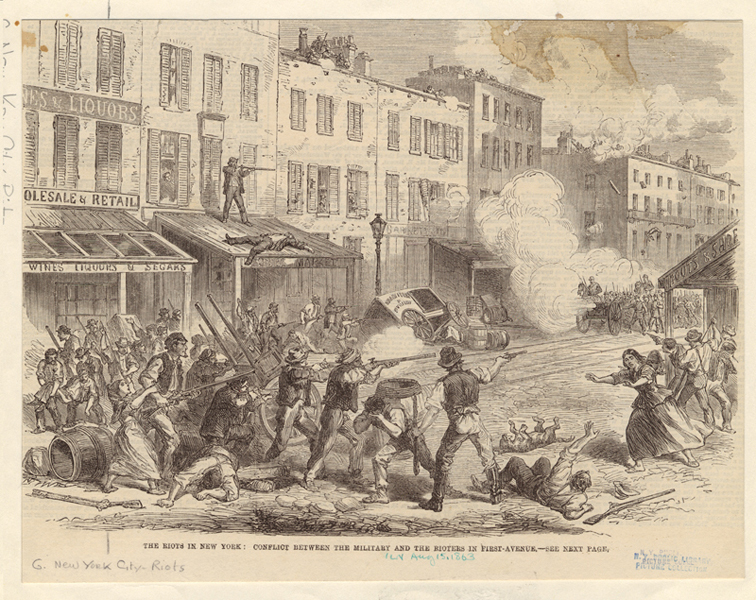

Depiction of rioters and police during the New York City draft riots of 1863. Harper’s Weekly, August 1, 1863. Source: Harper’s Weekly, Public domain

When recruiting for the army began in July 1863, a mob in New York wrecked the main recruiting station. Then, for three days, crowds of white workers marched through the city, destroying buildings, factories, streetcar lines, homes. The draft riots were complex — anti-Black, anti-rich, anti-Republican. From an assault on draft headquarters, the rioters went on to attacks on wealthy homes, then to the murder of Black people. They marched through the streets, forcing factories to close, recruiting more members of the mob. They set the city’s colored orphan asylum on fire. They shot, burned, and hanged Black people that they found in the streets. Many people were thrown into the rivers to drown. On the fourth day, Union troops returning from the Battle of Gettysburg came into the city and stopped the rioting. Perhaps four hundred people were killed. No exact figures have ever been given, but the number of lives lost was greater than in any other incident of domestic violence in American history.

Classroom Story

With post-pandemic kids, I was noticing some students in each class showing signs of disengagement and giving up on the process. I wanted to try something that covered all the rich content that this lesson did, but got and kept the middle school kids’ attention.

In a nutshell, after some introductory information, kids started out in random teams of three or four, and each team got an envelope of eight paper strip clues. I chose the clues from lesson materials that all seemed to relate to conditions for the Irish before they emigrated to the United States. Once kids read their clues and discussed them, they were instructed to locate their next clue. It took some groups a while, but they realized that there were rubber stamped bees in green ink on their envelope.

One drawer in my classroom also had an index card stamped with green bees. When students opened the drawer, they found a sign and pink paper with fill-in-the-blank sentences. They had to use their paper strips of information to fill in the blanks accurately. When they thought they had the answers right they had to “check out” with me. If they were wrong on any facts then they had to fix their mistakes and come back. If they were right, I took their first clue envelope and then showed them a new clue — in this case an index card with a rubber-stamped butterfly.

It went on from there until they reached the end of the mystery with a piece of candy for each student and a final paper they had to fill out individually.

A few years ago, I created a similar activity to the Draft Riot Mystery about Shays’ Rebellion.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn