As you know, the right-wing attacks on racial justice teaching have become more shrill, more frightening.

But despite claims of “political indoctrination” — or worse — specific descriptions of problematic teaching are scarce.

In fact, the white supremacist backlash does not take aim at bad teaching, but at good teaching.

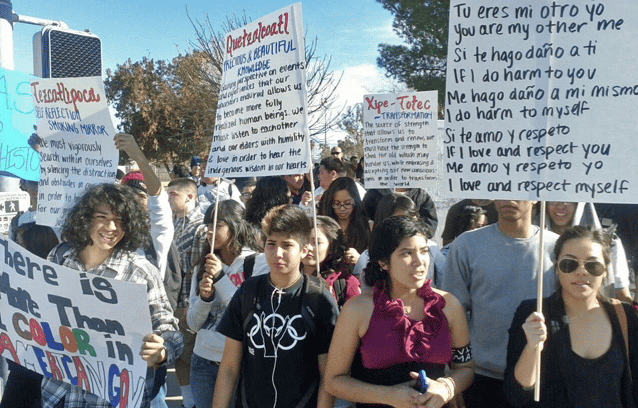

We saw this more than 10 years ago, with the banning of Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program.

Every single metric — from high school graduation rates to college attendance — testified to the program’s overwhelming success.

But the outcome that most upset the program’s opponents was that the curriculum focused on issues of racial inequality, and the history of activism. Students took their lessons to heart, and were becoming more active in working to make a difference.

Once a month, the Zinn Education Project will shine a light on the kind of people’s history teaching that the right wing seeks to suppress — and that we hope to spread.

Judge for yourself: “indoctrination” or an exploration of key moments of U.S. history, which can help students think more clearly about their society?

February

Adam Sanchez, high school teacher, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

After engaging in several lessons on Reconstruction, Sanchez asked his students what they had learned and whether they thought it was important for students to learn about this history and why. Here are a few of their responses. (It was hard to choose which to share — there are so many more brilliant responses.)

| I: “I didn’t learn much about Reconstruction before. I didn’t know how much power Black people had gained in this short period of time and had always just assumed it went immediately from slavery to Jim Crow. It is important for students to learn about this era because it represents a period of mass change that reveals that Black people don’t need saving, but have seized and defined freedom on their own.” |

| T: “I didn’t know that African Americans made significant progress during Reconstruction. . . It helps us understand why America is currently in the state it is in and the causes of the backlash, both to Reconstruction and Black progress today. But learning about Reconstruction also teaches us that if people come together, they can bring forth major political reforms, even changes to the Constitution.” |

| M: “I didn’t know that Black people were actually very powerful in the pre-Jim Crow period after the Civil War. This is probably a facet of U.S. history that’s frequently glossed over, and for a reason: People want to make it seem like Black people just went from struggle to struggle, when in fact, we were perfectly OK until the big political parties backstabbed us.” |

| S: “I learned there was an era of Black power that I didn’t even know existed, the school curriculum usually skips from Civil War to Jim Crow but there are so many things that happened in between. It’s a shame schools skip over it typically.” |

| W: “It is important to learn about Reconstruction because it can teach us about what the country could have been like if Jim Crow laws hadn’t come to pass.” |

| J: “I was not aware of the fact that during Reconstruction, African Americans actually were able to obtain significant power, serving as mayors, police officers, governors, judges, etc. |

March

Jordan Jones, middle school social studies teacher in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

My 8th graders have embarked on a significant journey this school year. We are attempting to understand how systems of racism in the United States have changed over time.

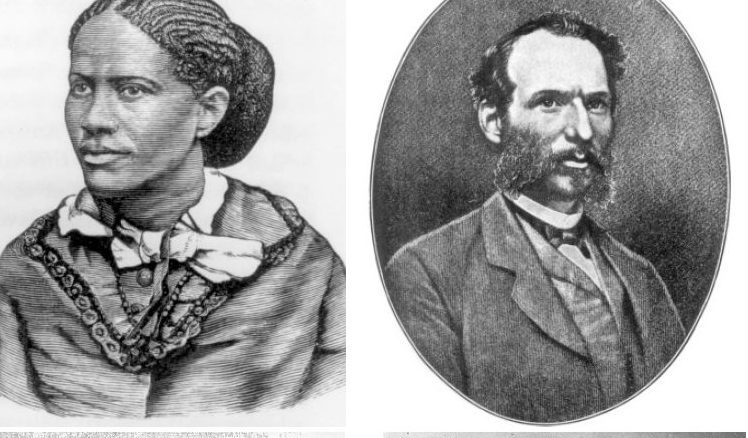

This past week we jumped from understanding the origins of race and racism through the system of slavery to the opportunity of Reconstruction following the Civil War. In order to get students imagining what was possible, we used “Reconstructing the South: A Role Play” to kick off this portion of our unit.

Students in another middle school class engaged in the Reconstructing the South lesson.

Students worked together in small groups and independently to answer each of the six questions within the activity. Students were engaged and collaborating effectively. However, the real magic took place when we had a whole class discussion/debate about the best solutions.

There were clearly two ways of thinking for the students involved. On one side were students who were thinking pragmatically and trying to be realistic about what they thought they could have actually accomplished at this point in history. On the other side were students focused on doing what they believed was morally right and what solutions would best ensure the continued liberation of recently freedmen and women.

The back and forth was powerful, and students were highly engaged in the process of not just thinking about history but participating in history.

Finally, at the end of the day was a comparison between the solutions that won the argument and what decisions were actually made in history. The shock and disappointment were palpable.

April

Jennifer Stangland, high school English teacher, San Francisco, California

Students in my class are well aware of the fact that things are not as they should be in the United States. Specifically, they are aware of the fact that the color of their skin, in many ways, determines where they live, the wealth their families have (or have not) acquired, and the opportunities presented to them throughout their lives.

However, despite the fact that awareness of inequality is high, the understanding of WHY inequality, racism, and segregation still exists remains a mystery to many students. Or, they have been indoctrinated with the not-so-subtle message that these issues still exist purely as a result of individual racism or prejudice. Not many of these young people realize that the dire circumstances they observe are the result of systematic policies that have shaped our country for decades, and are still doing so today.

As soon as students received and began reading their roles for the lesson How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century, I saw eyes begin to widen. Frantic highlighting and slight gasps of shock, along with giggles of disbelief, began to echo through the classroom.

This is when you know students are about to learn something, and learn something that matters. Minutes later, the entire class was on their feet, moving to find someone they could share their “story” with. Maybe it was a story of move-in violence, or the story of how their character used the prejudiced voting population in the United States for their own personal gains. Whatever it was, students were eager to share and to listen.

After nearly an hour of mingling, the class began to discuss what they discovered. Continue reading.

May

Nick DePascal, high school English teacher, Albuquerque, New Mexico

As we approached the end of the The Grapes of Wrath, words like “red” and “agitator” became more prevalent; the migrants became more radicalized in mind if not yet in deed; and the violence of the state was directed at those championing fairness and dignity. I used the Zinn Ed Project lesson, Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca to help students understand the history of the Red Scare and those who bravely stood up to McCarthyism.

Students were absolutely shocked by the many and various ways people from all jobs and walks of life were hounded and persecuted by their own government. Perhaps most importantly, students were able to see that these persecutions, while carried out under the guise of national security and the American way of life, were nothing more than thinly veiled attacks on those who would dare to challenge white supremacy and economic injustice. They were also amazed by the stories of resilience and strength of those they mixed with. One student reflected,

The people who were targeted all wanted fair and equal rights or knowledge. They targeted people and called them Communists for wanting things like flushing toilets and equal pay among Black communities. They targeted gays and people who fought against their injustices. I think a lot of what Tom and Casy experienced [in The Grapes of Wrath] was similar to the Red Scare characters in the lesson.

Stay tuned for more stories.

More Teacher Stories

Here are more stories from teachers about using people’s history lessons from the Zinn Education Project website and pledges to #TeachTruth.

What Do You Think?

Share your comments below. What do you think? If you are a teacher, share your classroom stories. Not a teacher? Please defend the right of young people to learn this history.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn