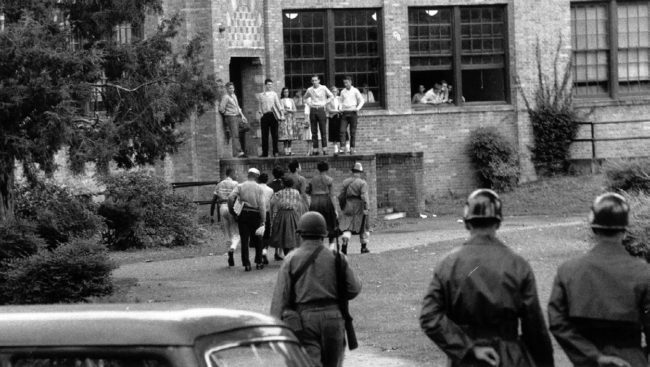

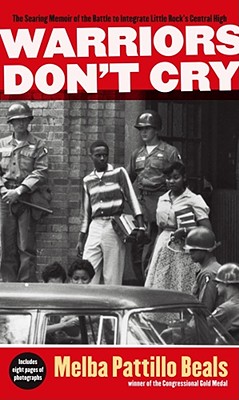

In her memoir, Warriors Don’t Cry, Melba Pattillo Beals walks students into the events of Central High School and makes them feel the sting of physical and emotional abuse the Little Rock Nine suffered as they lived the history of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Beals’ book tells the story of young people who became accidental heroes when their lives intersected a movement for justice in education, and they made the choice to join the movement instead of taking an easier path.

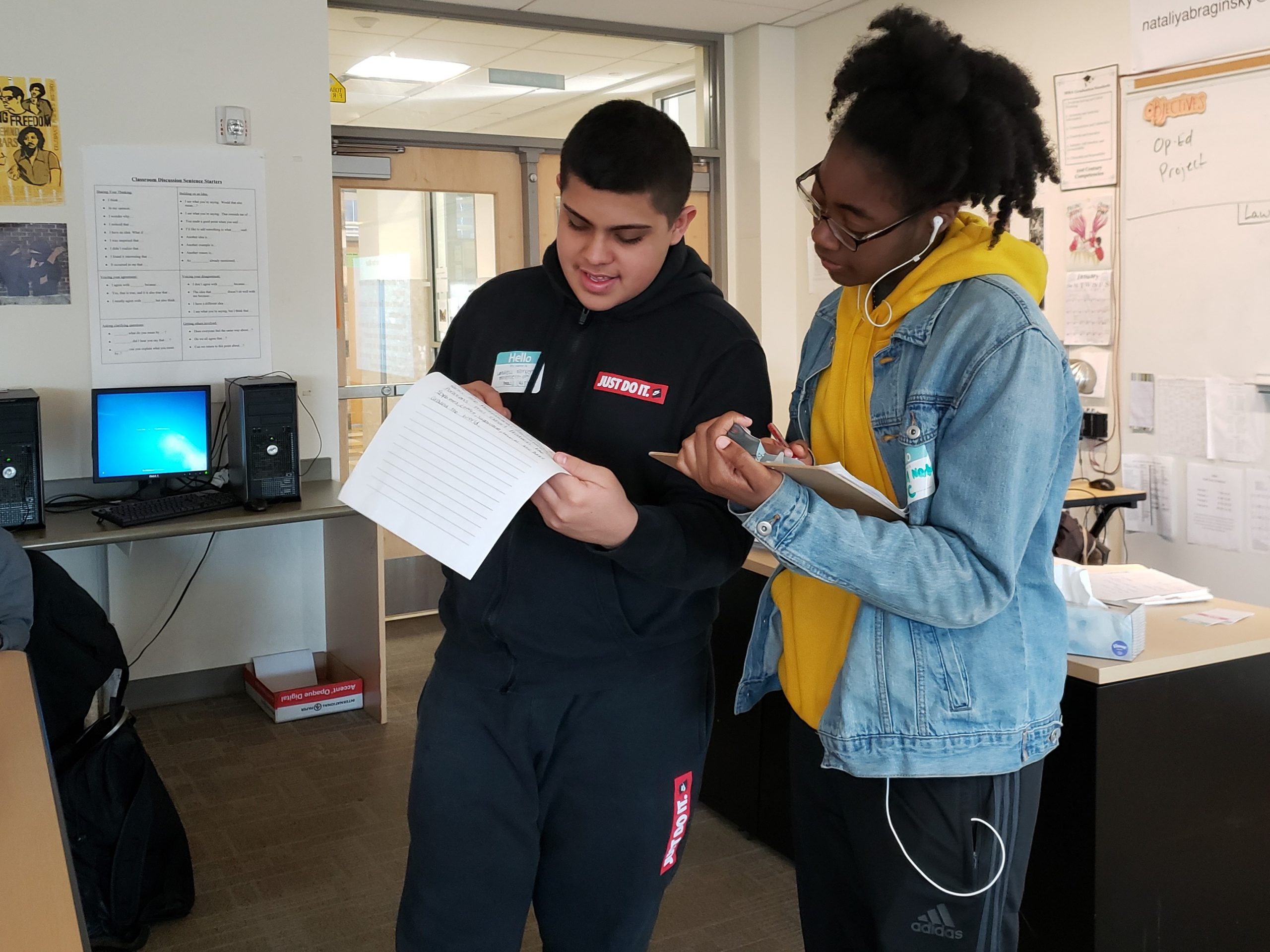

This teaching activity encourages teachers to begin with a role play to increase students’ knowledge of the historical context of segregation and the struggle for civil rights. Following the role play, students write a “Writing for Justice” narrative about an incident from their lives. They then engage in a literary mixer as they meet key players in the book.

This teaching activity encourages teachers to begin with a role play to increase students’ knowledge of the historical context of segregation and the struggle for civil rights. Following the role play, students write a “Writing for Justice” narrative about an incident from their lives. They then engage in a literary mixer as they meet key players in the book.

While students read the book, they keep a dialogue journal where they keep track of their insights and questions. They also identify targets and perpetrators of injustice as well as allies and bystanders. During the unit, students write an essay, poetry, and interior monologues. They draw literary postcards, engage in improvisations, and create character silhouettes to collect evidence for their essay. Linda Christensen also interlaces footage from Eyes on the Prize and Standing on My Sisters’ Shoulders for students to see and hear events described in the memoir. The films and other texts from the time period help students understand that the story of the Little Rock Nine was part of a larger movement to reshape U.S. society.

Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine with officers of the NAACP at their 49th annual convention. Mrs. Bates and the nine students received an award for their heroism during the school integration crisis in September, 1957. Pictured seated in row 1, left to right: Carlotta Walls, Melba Pattillo, and Elizabeth Eckford. Standing in Row 2 are, left to right: Terrence Roberts, Thelma Mothershed, Gloria Ray, Jefferson Thomas, Kivie Kaplan (of the NAACP), Minnijean Brown, Ernest Green, Daisy Bates, and James B. Levy, president of the Cleveland NAACP chapter.

This lesson was published by Rethinking Schools in Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-imagining the Language Arts Classroom. For more lessons like “Warriors Don’t Cry: Connecting History, Literature, and Our Lives,” order Teaching for Joy and Justice with two dozen lessons and articles for language arts and social studies classrooms by Linda Christensen.

This lesson was published by Rethinking Schools in Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-imagining the Language Arts Classroom. For more lessons like “Warriors Don’t Cry: Connecting History, Literature, and Our Lives,” order Teaching for Joy and Justice with two dozen lessons and articles for language arts and social studies classrooms by Linda Christensen.

Classroom Story

I use a number of lessons from the Zinn Education Project for my U.S. History classes at Hampshire Regional High School in Westhampton, Massachusetts. The diversity at my high school is mostly economic in nature as our student population is 96% white. I try to include as many different voices in American history as possible to increase my students’ understanding of the content.

Two of my favorite lessons are Burned Out of Homes and History, about the Tulsa Riot of 1921, and Warriors Don’t Cry, about the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Both activities allow students to try on someone else’s shoes and understand other perspectives in moments in history.

My students love to assume the roles. Recently, one of my students was upset with the Tulsa role she randomly received, presuming it was not long enough to be significant in the history. At the conclusion of the activity, however, she understood her role was critical to the loss of property in Tulsa and saw the wide reaching impact her person played in the tragic events.

My students are active, engaged and truly trying to meet other people during these activities. They’re eager to understand cause and effect as they place the event in the context of American history. In the Central High School integration lesson, my students use compelling and persuasive arguments to debate and build alliances. The noise level in the class tends to be louder. but the students are always on task and truly grasping the realities that people faced during the time.

The Zinn Education Project has been one of my go-to resources for all of my U.S. history classes. I teach college prep and honors level classes for the 10th and 11th grade and can easily adapt these lessons for use with those students, too.

Once again, The Zinn Education Project uses an excellent teacher to open children’s eyes to the Civil Rights Movement. I attended a few of Linda’s workshops and her “take and try” lessons were a wonderful addition to my Social Studies curriculum.

I have used this lesson with my students. It helps them to understand the individuals involved in a much deeper way. This is the way history should be taught. — Julian Hipkins III, high school U.S. history teacher, Washington, D.C.

There are so many great ideas here. I am trying most, if not all of them out. Thanks! — Grace Rivera