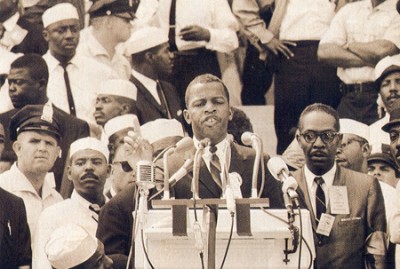

SNCC chairperson John Lewis at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is best remembered in popular culture for the speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Not for King’s demand for reparations with reference to “a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds’” but instead for the innocuous phrase, “I have a dream.”)

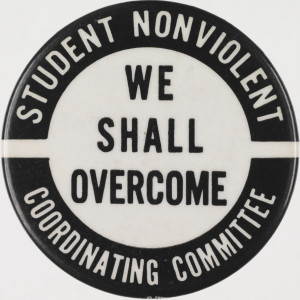

There is another March on Washington speech that merits remembering too, that is the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) speech delivered by the young SNCC chairperson from Alabama, John Lewis.

Lewis delivered what some called the most militant speech of the day and that was despite the fact that the text had been toned down.

Lewis delivered what some called the most militant speech of the day and that was despite the fact that the text had been toned down.

Howard Zinn wrote about the speech in SNCC: The Battle-Scarred Youngsters. (The Nation, October 5, 1963.)

There was one relevant moment in the day’s events at Washington: that was when the youngest speaker on the platform, John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), lashed out in anger, not only at the Dixiecrats, but at the Kennedy Administration, which had been successful up to that moment in directing the indignation of 200,000 people at everyone but itself.

The depth of Lewis’ feeling and the direction of his attack may have baffled Northern liberals, mollified recently by the Administration’s new Civil Rights Bill, by its bold words and by the President’s endorsement of the great March.

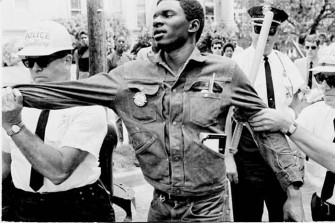

A voting rights activist is grabbed by police in Greenwood, Miss. on Freedom Day. Source: Ted Polumbaum Collection/Newseum

But John Lewis knew. . . that while the President and the Attorney General speak loud in Washington, their voices are scarcely whispers in the towns and the hamlets of the Black Belt.

Greenwood, Miss., just before the March, revealed in its own quiet way how the Deep South remains essentially untouched by resonant speeches in the national capital. Continue reading online.

As with all SNCC policies, speeches, and statements, writing was a collective effort.

And so was editing in this case. On the morning of August 28, 1963, some leaders of the March on Washington asked the SNCC staff to change sections of the speech, including these paragraphs:

In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the [Kennedy] administration’s civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late. There’s not one thing in the bill that will protect our people from police brutality. . .

We won’t stop now. All of the forces of Eastland, Bamett, Wallace, and Thurmond won’t stop this revolution. The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently.

Joyce Ladner noted in a New York Times interview,

I remember looking at [the speech]. Bayard and Rachelle looked at it. It was a communal statement; it was not John’s alone. So when the word got out that the White House and the Archbishop of Washington wanted him to change it, we said, Oh, hell no.

Eventually, the SNCC representatives agreed to make revisions, mainly because of their respect for A. Philip Randolph, who expressed his strong desire that the march not fall apart because of internal discord. As noted above, even with those changes, the SNCC speech was still among the most militant of the day and the earlier version had already been released to the press — so they SNCC leaders knew the full speech would be read. See both versions. Here is a more detailed description by Courtland Cox in an interview for Eyes on the Prize:

[President] Kennedy called up Archbishop O’Boyle who was the bishop of Washington and said to him “I want John Lewis’ speech changed.” Archbishop O’Boyle called A. Philip Randolph and Randolph called Bayard Rustin and they came to us about changing . . . two points . . . [that] criticized the Kennedy administration for lack of enthusiasm in enforcing civil rights law, and the whole question of alluding to violence, even though it’s historical violence, the allusion was too much in 1963.

Bishop O’Boyle said was he wanted a change or they were going to withdraw from the March on Washington. We refused to change it and in fact told Archbishop O’Boyle that he could leave, that was his problem. Then after we were adamant in not changing it, Bayard went to A. Philip Randolph and Randolph said, “You know I have waited twenty-two years for this March on Washington; please let us have unity at this last moment.” And it was only because of that plea from Randolph in terms of the whole generational thing, the whole historical perspective, that we agreed to, to make some changes, but I think the basic change in John’s speech came from the Kennedys who did not want to be criticized in, in this arena.

. . . The people came to town I think maybe about ten o’clock the crowd started arriving, they came to us about eleven and all this took place on the top, at the Lincoln Memorial where Lincoln sits looking down benevolently upon the colored. You know, we were up, under, where the statue is. There was a little typewriter we had up there and people were either sitting on the ground or a little box or a little wooden chair. So it wasn’t comfortable surroundings; things were hurried. And I guess John and myself — we were in our early twenties being very militant — [James] Forman was a little older, so I think the key players were Bayard, A. Philip Randolph, John Lewis, James Forman, and myself. And we went back and forth in terms of how this discussion was to go. After Randolph made his plea, then Jim Forman sat on a box, put a typewriter on another box, and he and I sat down and redid this speech in terms of the kinds of criticisms that the Kennedy administration had. Read more.

Students can compare both versions of the speech and listen to readings of the original speech in the film clip below.

Lewis later served as the U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th Congressional district, a position he held from 1987 until his death in 2020.

Here is a reading of the original text of the SNCC speech that John Lewis planned to give at the March on Washington, via Voices of a People’s History of the United States. The reading is by actor Danny Glover, introduced by Howard Zinn, on October 5, 2005 in Los Angeles, California.

More video clips can be found at the Voices of a People’s History website and in the film The People Speak.

Find lessons below for teaching about SNCC and the long and ongoing fight for voting rights.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn