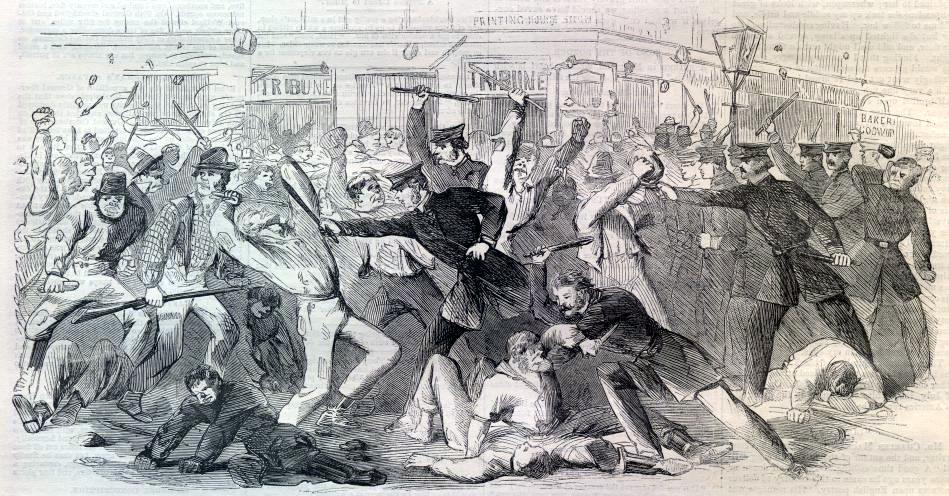

Somewhere back in school I learned about the 19th-century Irish Potato Famine: More than a million people starved to death when blight hit Ireland’s main crop, the potato. The famine meant tremendous human suffering and triggered a mass migration, largely to the United States. All this is true. But it is also incomplete and misses key facts that link past and present global hunger.

Beginning in 1845, blight did begin to hit Ireland’s potato crop, which was the staple food of the Irish poor. But all other crops were unaffected. And during the worst famine years, British-ruled Ireland continued to export vast amounts of food. . . In approaching the potato famine in my global studies class, I wanted students to see that hunger is less a natural phenomenon than it is a political and economic phenomenon.

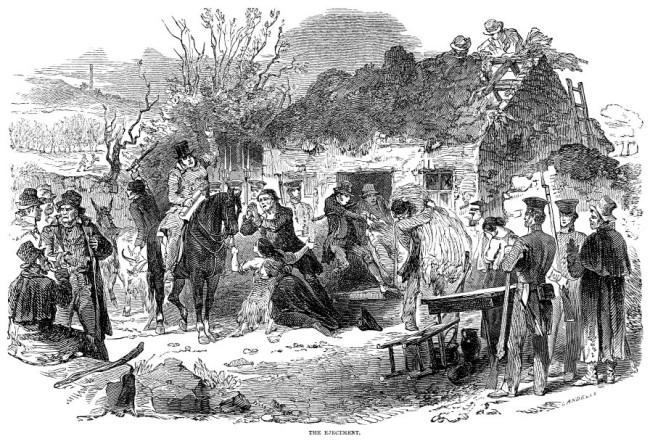

“The Ejectment,” The Illustrated London News, Dec. 16, 1848. See more images at the Views of the Famine website.

In 19th-century Ireland, food was a commodity, distributed largely to those who had the means to pay for it. Like today, the capitalist market ruled, and commerce trumped need. According to the Institute for Food and Development Policy/Food First, “Enough food is available to provide at least 4.3 pounds of food per person a day worldwide: two and a half pounds of grain, beans, and nuts, about a pound of fruits and vegetables, and nearly another pound of meat, milk, and eggs.” And yet, according to the organization Bread for the World, 852 million people in the world are hungry, and every day 16,000 children die of hunger-related causes. The main issue was and continues to be: Who controls the land and for what purposes?

This lesson was published by Rethinking Schools in the “Feeding the Children” (Summer 2006) issue.

This lesson was published by Rethinking Schools in the “Feeding the Children” (Summer 2006) issue.

For more lessons like “Hunger on Trial: An Activity on the Irish Potato Famine and Its Meaning for Today,” order the Rethinking Schools book, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth.

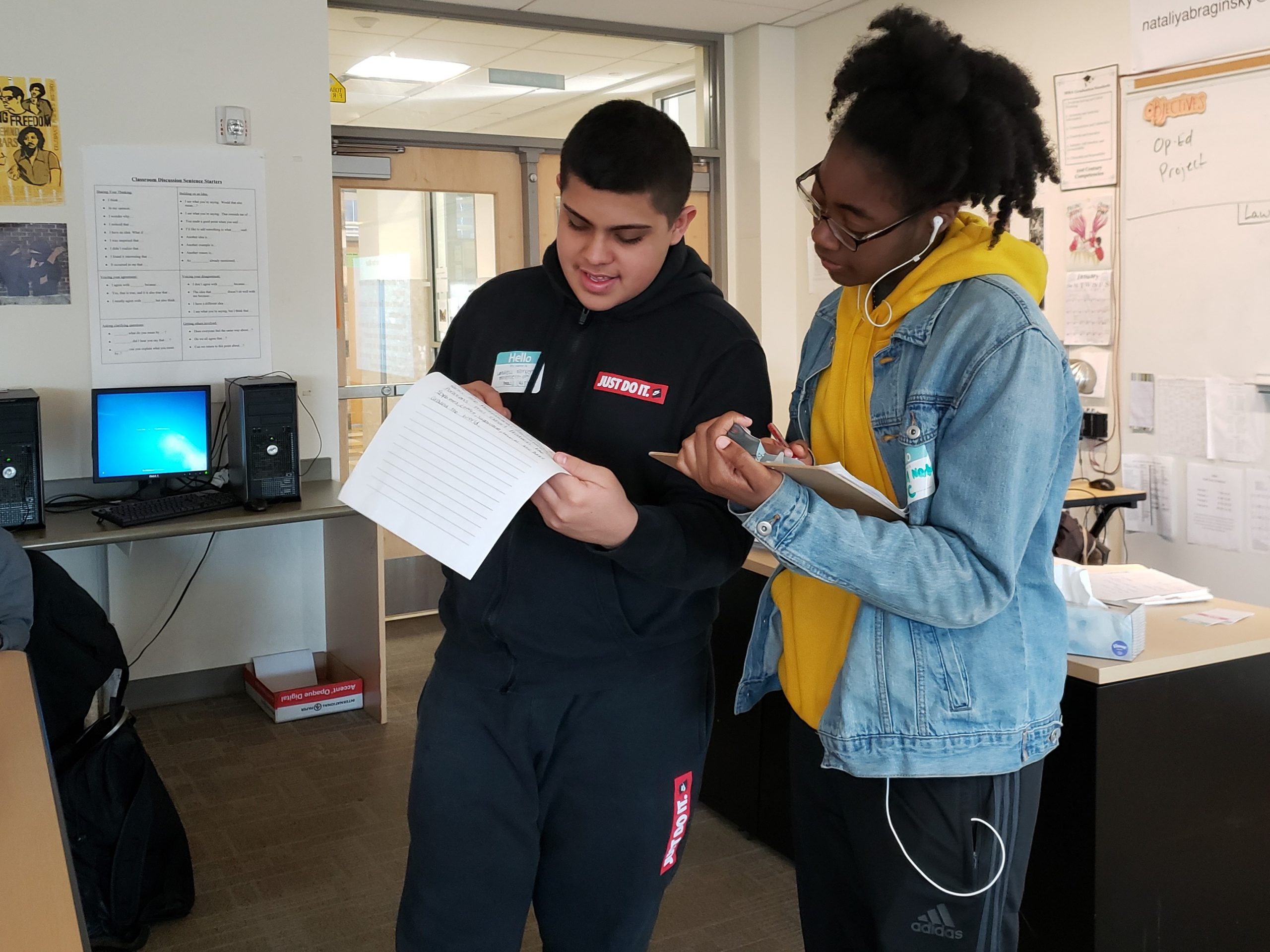

Classroom Story

I used the Hunger on Trial lesson to teach the long term causes of the Irish war of independence. I loved the way this lesson introduced perspectives and invited the students to think and investigate cause and effect.

I followed the lesson plan. The first day I played a YouTube video briefly introducing the Great Famine and then I distributed the infosheets to small groups of students. I asked them to read the materials and investigate why they may be at fault for the Great Famine.

The second day we had an in-class debate and students had to assess to what extent they were at fault and grade the blame for what happened from most to least liable. This invited students to apply critical thinking to the facts. Most of them rightfully agreed that the two most liable institutions were the government of the United Kingdom and the economic system.

The third day we dealt with the consequences of the Great Famine. I played the song “Skibbereen” with lyrics (the Sinead O’Connor version) and we discussed the economic, political, and social consequences of the famine, the mass migration from Ireland to the U.S. and the emergence of Irish nationalism, the Young Ireland rebellion, and groups like the Fenian Brotherhood and the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

It was a great way to teach about the emergence of nationalism, national liberation movements, capitalism and its consequences, and social justice.

This lesson looks awesome and I am going to try it out this week.