Liner Notes by Howard Zinn (1999)

Liner Notes by Howard Zinn (1999)

Before I became a college professor I was a shipyard worker. Before I was a writer I was a warehouse worker. But whatever I did, I was always a member of a labor union. I think the only job I had where I couldn’t join a union was when I was a bombardier in the Air Force — and it might have been a good thing if we had one — maybe we would have gotten together and asked the question: Why are we dropping bombs on this peaceful village this morning?

Whatever I was, blue collar or white collar, ditch digger or waiter (yes, I did those things, too) or faculty member in a large university, I was a worker. By that I mean: I was subject to someone’s authority, some corporation, some bureaucracy. Some invisible power could decide my wages, my hours, whether I would keep my job or lose it. That’s why I always joined a union. I was in a shipyard workers’ union, a warehouse workers’ union, a faculty union, and now I’m a member of the National Writers’ Union, which is part of the United Automobile Workers (don’t ask why — maybe it’s because I drive an automobile).

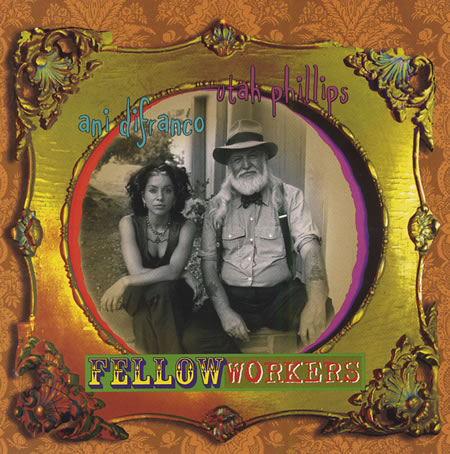

So when I picked up this new CD with Utah Phillips and Ani DiFranco, and saw it was entitled “Fellow Workers,” I wasn’t troubled by being associated with socialists or anarchists (who always started their speeches with “Fellow Workers!”). And I didn’t immediately think: Oh, unions, they’re corrupt bureaucracies run by fat cats smoking cigars and making deals with CEO’s over the heads of their members.

I knew there were such unions. But I knew there were other kinds, too. I also knew that unions are an absolute necessity for anyone who, standing alone, is helpless before the power of an employer, especially if that employer is a huge, wealthy corporation. And, as a historian who for many years has taught and written about the history of the United States, I knew that when workers were unorganized and on their own, they worked twelve-hour days, for starvation wages, and had to watch their ten-year old kids go to work in the mines or in the textile mills.

In the Constitution of the United States, there is a list of political rights, in the first Ten Amendments — the Bill of Rights. But the Constitution says nothing about economic rights. There is no legal right to food or housing or health care or education. When workers discovered they could not depend on the Constitution, on the government, on the courts, they did what people do to make democracy come alive. They organized and used direct action — strikes, boycotts, picket lines, demonstrations — to get the eight-hour day, and reasonable wages, and safety rules, at least the bare minimum for a decent life.

Singer/songwriter/guitarist Ani DiFranco has been playing since the mid-1990s, successfully living by the Do-It-Yourself ethos. Photo by Shervin Lainez.

Today, of the world’s largest 100 economies, 51 are not countries, but corporations, which have been merging with one another to amass enormous power. Because only 15% of the labor force in this country have union protection, these corporations can now set wages and fire at will (downsize is the polite term). They control the economy, they buy the political parties, they dominate the media.

Isn’t it clear, therefore, that all of us — whatever work we do — need to organize ourselves, as did blacks in the South, anti-war protesters and women demanding equality? Don’t we all need to gain control over our own work, our own lives, and see to it that the enormous wealth of this country is used for the good of all the people, and not the profits of corporations?

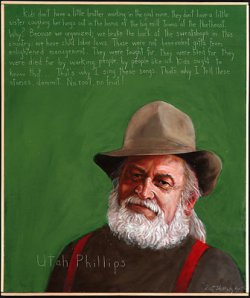

Utah Phillips (1935-2008) was a labor organizer, folk singer, storyteller, poet and the “Golden Voice of the Great Southwest.” He described the struggles of labor unions and the power of direct action, self-identifying as an anarchist. He often promoted the IWW in his music, actions, and words. Portrait by Robert Shetterly.

So, when two people with the talent and social conscience of Utah Phillips and Ani DiFranco collaborate to bring a message of defiance, disobedience, and solidarity, that is to be welcomed. They remind us of a history that we were not taught in our schools and colleges. They tell us of people, who like us, seemed to be powerless before the might of corporations, but who struggled and fought back, and changed their lives.

They remind us of Mother Jones who, in her eighties, went into the mining towns of West Virginia and Colorado and the textile mills of Pennsylvania and gave the families hope that they could challenge the power of the bosses. She organized the women, she led children on a long march from Pennsylvania to New York to confront President Theodore Roosevelt and demand an end to children working in the textile mills. The youngsters carried signs saying: “We want time to play.” That was just the beginning of a long campaign which finally abolished child labor.

I listen to the haunting song “Joe Hill,” as Utah Phillips sings it, with the soulful touch of Ani DiFranco in the background, and I am reminded of that magnificent bunch of people who in the early years of the 20th century formed the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW or Wobblies, as they were called. Their slogan was “One Big Union” and they brought everyone into one union, including people who had been shut out of the old conservative unions, black workers, women, immigrants.

It was IWW organizers who helped the workers of the textile mills in Lawrence, Massachusetts when, in 1912, they went out on strike against their miserable wages and working conditions. They were mostly women, and from many different countries, speaking different languages, but they were united in their determination.

The Lawrence strikers found support from people all over the country — true solidarity. When they could not feed their children through the long winter months of the strike, families in New York and Philadelphia volunteered to take the children. When police attacked mothers and children at the railroad station, they still refused to surrender to the textile mill owners. The signs they carried said “We Want Bread, and Roses Too.” And they won their strike.

The songs on this disc, the stories told, in Utah Phillips’ extraordinary style, bring back the history, but even more, the feelings of people struggling together for a better life. Those feelings connect with us today, because all of us live in a society dominated by corporate power, where profit comes before people.

In this situation, we need to join together to defend our humanity, our dignity as individuals. We need to remind everyone of what the Declaration of Independence promised, that all human beings, here and everywhere in the world, have an equal right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And we will use our energy, our talent, to achieve those aims. with the good feeling that people have always had when they worked together for justice.

So I listen, and I am encouraged to know that others feel as I do.

—Howard Zinn

From the album Fellow Workers by Ani DiFranco and Utah Phillips | Released by Righteous Babe Records.

RIP Howard