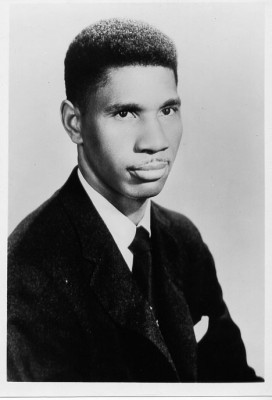

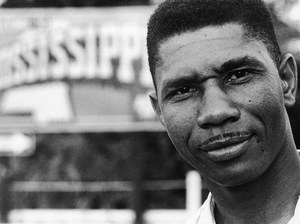

Medgar Evers

On June 12, 1963, WWII veteran Medgar Evers was murdered in the driveway outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi.

As a field worker for the NAACP, Evers had traveled through his home state encouraging African Americans to register to vote. He was instrumental in getting witnesses and evidence for the Emmett Till murder case and others, which brought national attention to the terrorism used against African Americans.

Profile by Dernoral Davis. Reprinted from the Mississippi Historical Society, Mississippi History Now.

Between 1952 and 1963, Medgar Wiley Evers was one of Mississippi’s most impassioned activists, orators, and visionaries for change. He fought for equality and fought against brutality.

Born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, Medgar was one of four children born to James and Jesse Evers. His father worked in a sawmill and his mother was a laundress. Evers’s childhood was typical in many ways of black youths who grew up in the Jim Crow South during the Great Depression of the 1930s and in the years preceding World War II. As a youth, Evers’s parents showered him with love and affection, taught him family values, and routinely disciplined him when needed. The Evers home emphasized education, religion, and hard work.

Among his siblings, Evers spent the most time with Charles, whom he idolized. As Evers’s older brother, Charles protected him, taught him to fish, swim, hunt, box, wrestle, and generally served as a sounding board for many of Medgar’s early experiences. He attended all-black schools in the dual and segregated public educational system of Newton County. Segregated public education meant long walks to school for the Evers children. The schools had few resources and operated with outdated textbooks, few teachers, large classes, and small classrooms without laboratories and supplies for the study of biology, chemistry, and physics.

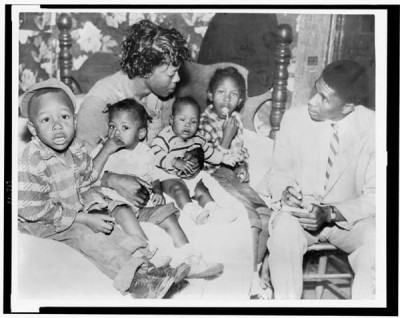

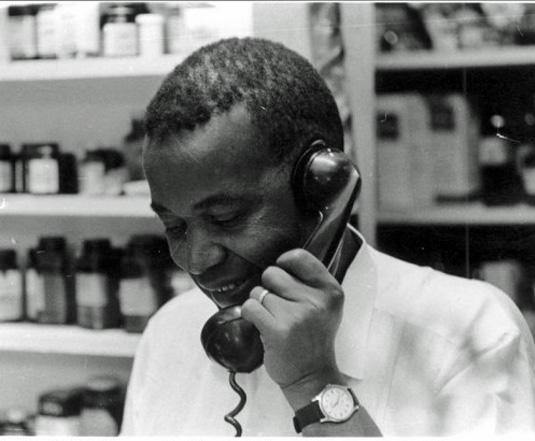

Medgar Evers is interviewing Beulah Melton about the murder of her husband, Clinton Melton, in 1955. Mrs. Melton died (likely killed) before she could testify. Click photo to learn more. This is one of many murder cases Evers investigated. Photo: Library of Congress.

Besides his under-funded public education, Evers on occasion saw and witnessed acts of raw violence against blacks. On these occasions, Evers’s parents and older brother could not shield him from the realities of a society built on racial discrimination. At about age 14, Evers observed to his horror the dragging of a black man, Willie Tingle, behind a wagon through the streets of Decatur. Tingle was later shot and hanged. A friend of Evers’ father, Tingle was accused of insulting a white woman.

Evers later recalled that Tingle’s bloody clothes remained in the field for months near the tree where he was hanged. Each day on his way to school Evers had to pass this tableau of violence. He never forgot the image.

A World War II Soldier

At the end of his sophomore year of high school and several months before his eighteenth birthday, Evers volunteered and was inducted into the United States Army in 1942. During his tour of duty in World War II, Evers was assigned to and served with a segregated port battalion, first in Great Britain and later in France. Though typical at the time, racial segregation in the military only served to anger Evers.

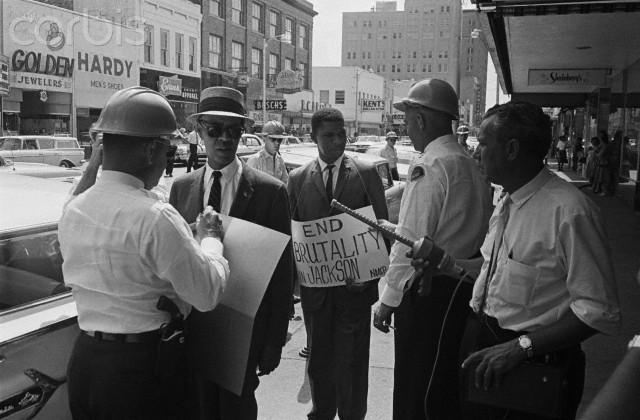

Roy Wilkins and Medgar Evers being arrested on June 1, 1963 in Jackson, Miss. Evers was murdered just 11 days later. Photo: Corbis Images.

By the end of the war, Evers was among a generation of black veterans committed to answering W. E. B. Du Bois’s clarion call of nearly three decades earlier: “to return [home] fighting” for change.

Upon returning home, the initial “fight” for Evers was to register to vote. For Evers voting was an affirmation of citizenship. Accordingly, in the summer of 1946, along with his brother, Charles, and several other black veterans, Evers registered to vote at the Decatur city hall. But on election day, the veterans were prevented by angry whites from casting their ballots. The experience only deepened Evers’s conviction that the status quo in Mississippi had to change. Continue reading.

Related Resources

Classroom Lesson

Meet Medgar Evers. By Teaching for Change.

An introductory lesson for middle and high school students on Medgar Evers’ life and legacy.

Links to Key Investigations and Events

Below are links to the Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement and other websites with descriptions of some key organizing and advocacy efforts by Medgar Evers. These provide an introduction to the wide range of issues and tactics addressed by Medgar Evers and the southern freedom movement at the time.

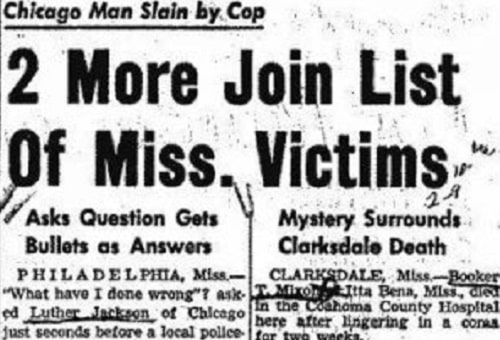

Rev. George Lee Murder Investigation: Medgar Evers insisted on an investigation of the May 7, 1955, murder of voting rights activist Rev. George Lee. It remained a cold case, however, it received more attention than it would have otherwise thanks to the brave work of Evers.

Emmett Till Murder Investigation: Medgar Evers played a key role in securing the involvement of the NAACP in the effort to publicize and bring to justice the case of the August 1955 murder of 14 year old Emmett Till. He also helped secretly secure witnesses for the case.

Clinton and Beulah Melton Murder Investigation: Medgar Evers investigated the murder of Clinton Melton on Dec. 3, 1955. Clinton’s wife died, likely murdered, a week before she was to testify in the case.

James Meredith’s Fight to Desegregate Ole Miss: Medgar Evers helped James Meredith in his effort to enroll at the University of Mississippi in 1962. He secured the NAACP’s legal team, headed by Thurgood Marshall, to assist Meredith. Evers himself had been denied admission to Ole Miss law school in 1954.

Jackson, Mississippi Boycotts of 1962-63: These include boycotts of the segregated county fair and business district.

Films

Directed by Michael Cory Davis. 2010. 1 hour 11 min.

This two-part documentary on Medgar Evers, produced by the Mad Men TV series, provides extensive interviews with Myrlie Evers-Williams (widow), Charles Evers (brother), Reena Evers-Everette (daughter), Kestin Boyce, Derrick Johnson, and more. It is too long for classroom use, however, it provides useful background information for teachers and clips of the interviews could be shared with students.

Myrlie Evers addressing a NAACP Freedom Rally at Howard University. At far left is Evers’ son Darrell. 8/25/1963. Photo: ©Bettmann Corbis.

About Myrlie Evers-Williams

Myrlie Evers-Williams has long been a pioneer in the struggles for racial justice and women’s equality. She fought for decades to gain justice in the assassination Medgar Evers, worked tirelessly for civil rights, ran for political office, and from 1995-1998, served as chair of the NAACP. She raised three children, Darrell Kenyatta, Reena Denise, and James Van Dyke.

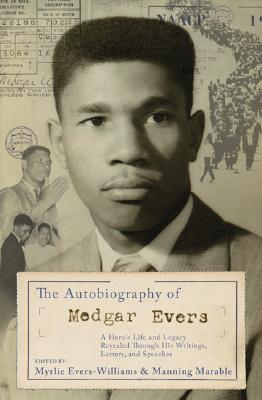

Evers-Williams has co-written three books: For Us, The Living; Watch Me Fly: What I Learned on the Way to Becoming the Woman I Was Meant to Be; and The Autobiography of Medgar Evers.

She is currently serving as a distinguished scholar-in-residence at Alcorn State University and directing the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute.

I would like to meet with Ms. Evers and since I was a state witness in the trial of Byron De La Beckwith. I still have a lot to tell and things I want to tell her truth must not be held back. We must tell history as we have lived it. Peggy Morgan

I was born ten days after he was assasinated. I was named in his honor as I have tried to live my life in his honor. Ieven attend Alcorn State to learn as much as I could. I had an instructor Dr. Alpha Morris who was one of his classmates and I picked her brain as much as I could. I have met Myrlie Evers-Williams three times in my life and I have three books she has written all autographed by her. I joined Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. while at Alcorn State and have a college fraternity brother who joined with and his name is Medgar K. Wells. His father was Houston Wells the neighbor who fired his shotgun that night and drove Medgar Evers to the hospital in his station wagon. My friend Medgar told me this story and then I saw a video with Mrs. Evers-Williams and she said the same thing verbatim….I also have a friend named Gail and her parents were in the Evers wedding 12/24/1951. Medgar Wiley Evers is my hero and Myrlie Evers-Williams is my shero.

Has anyone stepped forward to accurately tell his story through a full feature documentary?

I would like to see and read all of these books. Some of this I never knew, but we cannot stop the fight for equality. Too many lives have been lost for freedom.