An unfortunate but recurring feature of U.S. history has been the tendency of political leaders to lie to the American people. The mainstream media have often simply reported these lies with little or no critique, functioning as “stenographers to power,” to borrow from the title of a book by media critic Norman Solomon. This is not to say that everything government leaders tell us is a lie. However, an informed and skeptical public is perhaps the best defense against statements that mask policies that undermine human rights, at home and abroad.

A U.S. history course should seek to nurture this informed skepticism in students. It should encourage them to question the premises of textbooks, newspapers, films, and speeches of political leaders. It should ask them to check assertions against historical evidence.

The speech Andrew Jackson delivered to Congress in December 1830 is a good example of how leaders rely on widespread ignorance to promote their policies. For example, anyone even remotely familiar with the Cherokee people at the time would know that it was ludicrous to characterize them as “a few savage hunters.” Some people surely knew that this was a wildly inaccurate description, but didn’t care because they supported Jackson’s Indian policy. But others almost certainly assumed that, since Jackson is president, he must know best. In instances such as this, people’s critical capacities, or lack of them, have life and death consequences. In my experience, students find it exhilarating to discover that they have the knowledge and ability to critique the pronouncements of a U.S. president.

Classroom Stories

A deeper look into Andrew Jackson’s treatment of Native Americans is always a powerful moment in the development of students’ questioning of public officials and the words they speak.

We use “Andrew Jackson and the ‘Children of the Forest’” as part of a mock trial. By the end of the trial, the light bulbs going off as students compare words with actions. “What did he mean by ‘civilizing’ the natives?” “What does it mean in the era of expanding democracy that people should have perhaps even less faith in their leaders?”

It sets the stage for a continued focus on people’s history and a framework for how to view the rest of U.S. history, especially in the context of 20th century empire-building.

I’m a white high school history and English teacher in The Bronx, where 98 percent of the school’s population are students of color. I do my best every single day to give them an equitable education and I often seek out resources from Zinn Education Project. Like many people in this country (especially white people), reading Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States was a real eye-opener and really forced me to confront the country that I was born and raised in. The spirit of that book obviously lives in so many resources on this website.

One of the resources I have used is Andrew Jackson and the ‘Children of the Forest.’ For 11th Grade, I teach an AP Humanities class with a co-teacher. In this class, which meets 11 times a week, we teach both AP English Language and AP U.S. History. We try to integrate our curricula as much as possible and we adapted this lesson for the purposes of our class. Because of the co-teacher dynamic, we are able to include students with learning disabilities and ELL students.

On the day of the lesson, our students came to class prepared with arguments for why the Cherokee and Seminole peoples should be allowed to stay on their land. Our school does not have a library, so the students had to conduct that research on the on their own. Using what they found, students made group posters detailing their reasons why Native people should not be removed from their land. We then conducted a “History Fair,” and students did a gallery walk listening to their peers make their case for the people not to be removed.

After the gallery walk, we conducted a close reading of Jackson’s speech and analyzed it for rhetorical strategies. The next day, the students wrote an AP rhetorical analysis essay on Jackson’s speech. The first half of the lesson gave students the context for Jackson’s speech and the insidious purpose he used rhetorical strategies for. I’m proud to say they did very well in their essays.

Thank you, Zinn Education Project, for all that you do.

Because the lessons Andrew Jackson and the Children of the Forest and Constitutional Role Play revolve around groups who were (are?) traditionally silenced, they appealed to several of my students who often choose to listen rather than to give voice in the classroom. One girl, in particular, who is very shy and does not like to speak in class, chose to deliver part of the speech for her group as Enslaved Africans at the Constitutional Convention. It was a big moment.

Another amazing moment for us was during the Indian Removal Speeches. As liberal-minded New Yorkers, we were really shocked by the group who covered Andrew Jackson’s administration. Shocked, because Jackson’s Administration sounded so convincing! Indian Removal seemed like a good idea after listening to them! We had a really rich conversation directly following the activity about the power of political rhetoric and how we had previously counted ourselves immune to it.

Because both of these lessons [Andrew Jackson and the Children of the Forest” and Constitutional Role Play] revolve around groups who were (are?) traditionally silenced, they appealed to several students who often choose to listen rather than to give voice in the classroom. One girl, in particular, who is very shy and does not like to speak in class, chose to deliver part of the speech for her group as Enslaved Africans at the Constitutional Convention. It was a big moment.

Another amazing moment for us was during the Indian Removal Speeches. As liberal-minded New Yorkers, we were really shocked by the group who covered Andrew Jackson’s administration. Shocked, because Jackson’s Administration sounded so convincing! Indian Removal seemed like a good idea after listening to them! We had a really rich conversation directly following the activity about the power of political rhetoric and how we had previously counted ourselves immune to it. —Mia Sacilotto, middle school humanities teacher, Brooklyn NY

I modified the trial into a larger unit of historical thinking. Students were given the role of investigative journalists or detectives building a case for/against Andrew Jackson or the United States in general (this wasn’t only Jackson that railed against Indians).

We used primary sources including:

1. Elias Boudinot’s letter to Cherokee in 1837 (Stanford’s Reading Like a Historian lesson on Indian Removal)

2. Jackson’s speeches in 1830 (January & December) to congress.

3. Worcester vs Georgia Supreme Court case

4. Supporting and Opposing viewpoints from congressmen of the time (Lewis Cass, Sec of War for Jackson, Theodore Frelinghuysen,

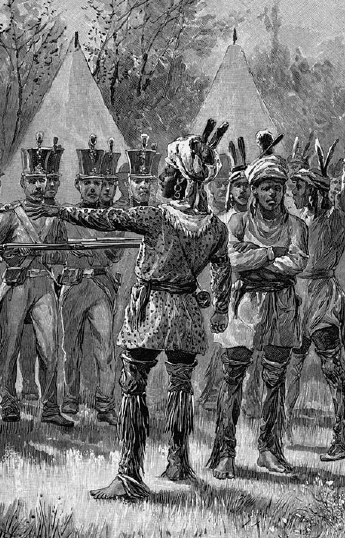

5. Propaganda – Andrew Jackson as “The Great Father” painting, “Hunting Indians in Florida with Bloodhounds”

6. Past/Future president’s remarks about Native American removal – Washington, Jefferson, Monroe, Jackson, Van Buren, Taylor, etc

Then congress had their hearings (instead of the trial) in 1840 so the different interest groups could have hindsight to all the events as they presented their case for/against removal. Congress also had to look up actual congressmen from the 26th congress (1840) and take on that role during the hearings.

William Holland Thomas, “Little Will”, the only white Chief of the Cherokee, spent his entire fortune battling President Jackson to keep about 14 villages of Cherokee in western North Carolina and east Tennessee.

What about those like Senator Frelinghuisen who opposed the removal. Are they included?