In “Stripmining Black History Month,” Jeff Biggers writes that “the neglect and degradation of a region and its history have always mirrored the neglect and abuse of the land.” And there is no more abused land in the United States than Appalachia, where coal companies continue to scrape away mountains to get at the thin coal seams buried within. The coal companies call everything that is not coal, “overburden” — streams, trees, animals, plants. Surely history itself is also a burden for the coal companies, because if we knew our history, we would know the rich legacy of activism that has characterized Appalachia — activism that does not conform to the whitewashed ignorant “hillbilly” stereotypes that the rich and powerful have found so convenient to promote.

In this Black History Month column, first published several years ago, Biggers asks us to remember the role of African Americans in shaping — and being shaped by — a region of the country that is too often forgotten.

By Jeff Biggers

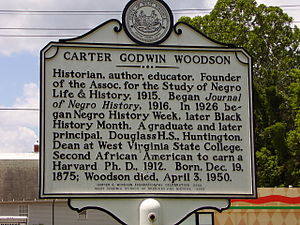

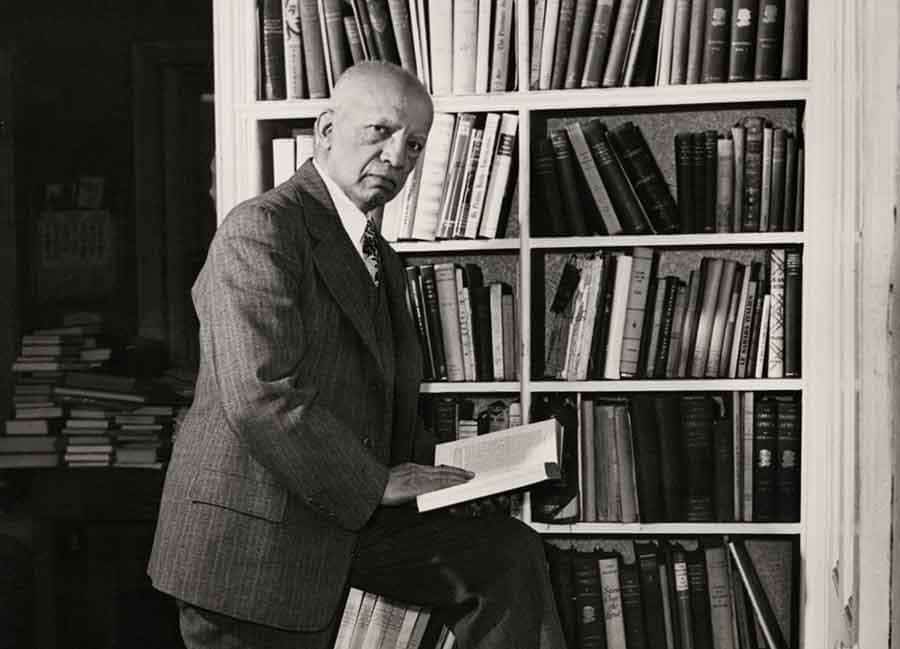

Carter G. Woodson. Source: Wikipedia Commons

Roadside marker in Huntington, WVa. Source: Wikipedia Commons

“I am ready to act, if I can find brave men to help me.” —Carter Woodson

As schools, communities and politicians across the country celebrate Black History Month in February, they will be remiss if their lessons don’t include the coal fields of Fayette County, West Virginia. There, in the 1890s, a teenage African American followed his brothers into the coal mines, serving what Carter Woodson called his “six-year apprenticeship.” In the evenings, the young Woodson would gather with other black coal miners, read the newspaper, and listen to their extraordinary stories of life underground, and their struggles during the Civil War and Reconstruction era.

The daily history lessons among African Americans in Appalachia were not lost on Woodson. He later wrote that his “interest in penetrating the past of my people was deepened and intensified” during these sessions among coal miners in Fayette County. Woodson managed to return to high school in Huntington, West Virginia — the access to education for African Americans being one of the reasons his family had chosen to come to Appalachia — and earned his diploma in two years. He moved on to earn a degree at Berea College, which had been founded in the hills of eastern Kentucky by abolitionists in 1855, the University of Chicago and then a Ph.D. in history at Harvard University.

Woodson went on, of course, to become the “Father of Black History,” and one of our country’s most celebrated historians. Few people realized, however, that West Virginia once again played prominently in Woodson’s career in 1920, when the young black professor lost his job at Howard University and became a dean at the West Virginia Collegiate Institute. There in West Virginia, Woodson finally received a substantial grant from the Carnegie Foundation that allowed him to return to Washington, D.C. and set his Association for the Study of Negro Life and History on a course for world acclaim.

Woodson’s and Black History Month’s largely overlooked origins in West Virginia are not the only casualty in our selective memory on American history.

A century after Woodson’s tenure in the coal mines in West Virginia, another “first” took place in Fayette County. In 1970, the first mountaintop removal operation was launched on Cannelton Hollow in an area once called Bullpush Mountain. Thirty-eight years later, mountaintop removal practices — the process of literally blowing up mountains, and dumping the waste into waterways and valleys, in order to cheaply remove coal — have destroyed over 450 mountains and neighboring communities, displaced miners, and strip-mined the cultural landscape in the Appalachian region.

This catastrophic form of coal mining has robbed Appalachia of too much of its history in the process. If anything, it should remind the nation that the neglect and degradation of a region and its history have always mirrored the neglect and abuse of the land.

This catastrophic form of coal mining has robbed Appalachia of too much of its history in the process. If anything, it should remind the nation that the neglect and degradation of a region and its history have always mirrored the neglect and abuse of the land.

In a speech at Hampton Institute in Virginia, Woodson once reminded the audience: “We have a wonderful history behind us. . . . If you are unable to demonstrate to the world that you have this record, the world will say to you, ‘You are not worthy to enjoy the blessings of democracy or anything else.’ They will say to you, ‘Who are you anyway?'”

Appalachians understand this bitter historical reality more than any other citizens in the United States. Black Appalachians, especially.

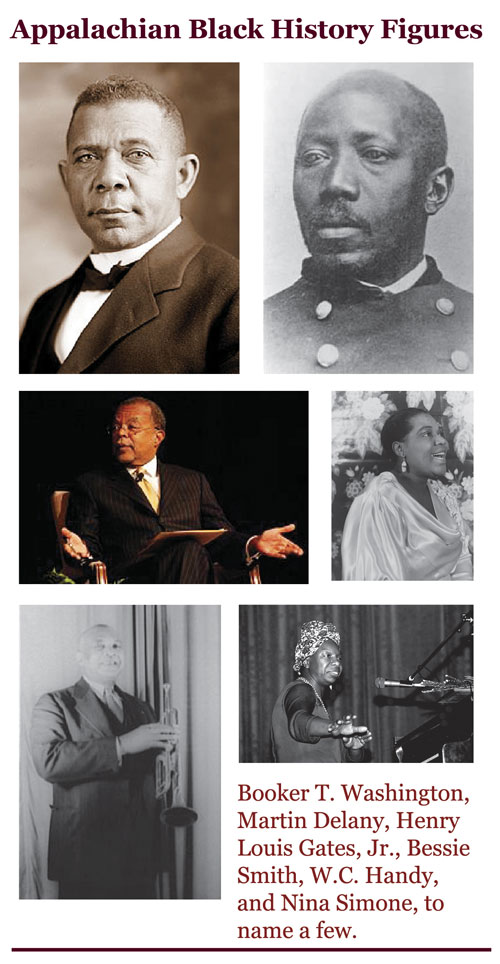

Last year, for example, I was supposed to speak at a school in Chicago in February. But the organizer called me at the last moment and asked to reschedule until April, since a book I had written about “those people down there” didn’t relate to Black History Month. But Black History Month was launched by an Appalachian coal miner, I told my host. Booker T. Washington, the most celebrated black spokesman from last century, also emerged out of the coal mining communities in Appalachia; Martin Delany, the first black nationalist in the 19th century, who helped to launch Frederick Douglass’ first newspaper, came out of West Virginia. So did Henry Louis Gates, the prominent African American literary critic at Harvard University.

Last year, for example, I was supposed to speak at a school in Chicago in February. But the organizer called me at the last moment and asked to reschedule until April, since a book I had written about “those people down there” didn’t relate to Black History Month. But Black History Month was launched by an Appalachian coal miner, I told my host. Booker T. Washington, the most celebrated black spokesman from last century, also emerged out of the coal mining communities in Appalachia; Martin Delany, the first black nationalist in the 19th century, who helped to launch Frederick Douglass’ first newspaper, came out of West Virginia. So did Henry Louis Gates, the prominent African American literary critic at Harvard University.

I went on. Do you know that Bessie Smith, the “Empress of the Blues,” took her songs from the streets of Blue Goose Hollow in Chattanooga, just as W.C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues,” composed his masterpieces from the sounds of his native hills of northern Alabama. That Nina Simone, the “High Priestess of Soul,” always performed folk ballads from her native western North Carolina mountains. That, in fact, Black guitar and banjo players were the stylists for much of the early country music, gospel, and folk songs.

Did you know that four months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus in 1955, she took a seat at the Highlander Folk School in the backwoods of Tennessee, where she attended strategy session on social action led by so-called “radical hillbillies.” That the first desegregated school to graduate a Black student in the South was in the mountains of Tennessee?

And did you know that the United Mine Workers have always been an integrated union? Coal miners and coal mining communities in Appalachia and around the country should be celebrated during Black History Month, not dismissed or forgotten.

The struggle of humanity against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting, author Milan Kundera wrote about his native Czech Republic. He added in an interview with American novelist Philip Roth, “Forgetting is a form of death ever present within life.”

There is a lot of “forgetting” and death taking place in our nation’s memory about Appalachia’s destruction today.

Carter Woodson, who was mocked when he first arrived in Washington, D.C. for his “hayseed clothes,” never forgot the importance of his origins.

Hopefully, some brave men and women will act to preserve Woodson’s and Appalachia’s great heritage before it is strip-mined into oblivion.

▸ Used with permission of the author. Originally published January 29, 2008, at HuffingtonPost.com.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn