A people’s history flips the script. When we look at history from the standpoint of the workers and not just the owners, the soldiers and not just the generals, the invaded and not just the invaders, we can begin to see society more fully, more accurately. The more clearly we see the past, the more clearly we’ll see the present — and be equipped to improve it.

READ MORE▸ The Zinn Education Project Approach to History

The Zinn Education Project approach to history starts with the premise that the lives of ordinary people matter — that history ought to focus on those who too often receive only token attention (workers, women, people of color), and also on how people’s actions, individually and collectively, shaped our society.

This approach stands in direct contrast to the traditional textbook history. As anyone who has ever cracked a history textbook can affirm, they’re boring. Passionless, story-poor, the books feign Objectivity. There is a lot of “us,” and “we,” and “our,” as if the texts are trying to dissolve race, class, and gender realities into the melting pot of “the nation.” As Howard Zinn writes,

Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, most often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex.

Societies are dynamic, conflict-ridden, with power played out in every aspect of life. Historians cannot remain outside or “above” these struggles. None of us can. Our lives, our occupations, our consumer choices — and, yes, how we tell history — all take sides, and help move the world in one direction or another.

“Anyone reading history should understand from the start that there is no such thing as impartial history,” Howard Zinn writes in a book of essays, Declarations of Independence.

All written history is partial in two senses. It is partial in that it is only a tiny part of what really happened. That is a limitation that can never be overcome. And it is partial in that it inevitably takes sides, by what it includes or omits, what it emphasizes or deemphasizes. It may do this openly or deceptively, consciously or subconsciously.

The textbooks most of us have read as students or have been assigned to teach throughout our careers do not acknowledge their biases. Yet nearly all concentrate on those at the top — the presidents and diplomats, the generals and industrialists. It’s a winner’s history, and implicitly tells students: Pay attention to the victors and disregard the rest.

A people’s history flips the script. When we look at history from the standpoint of the workers and not just the owners, the soldiers and not just the generals, the invaded and not just the invaders, we can begin to see society more fully, more accurately. The more clearly we see the past, the more clearly we’ll see the present — and be equipped to improve it.

▸ Continue reading

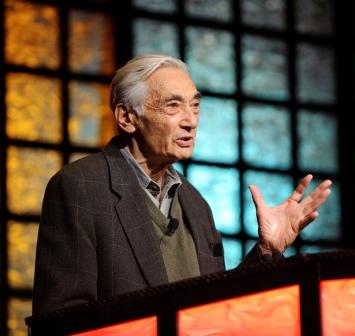

Howard Zinn Talks to Teachers

We are pleased to share the keynote address Howard Zinn gave at the 2008 National Conference for the Social Studies (NCSS) conference. He offers clear examples of how history teachers can help students think outside of the box. This is an excellent film to be shown in parts or in full for staff discussion.

WATCH▸ Video

Howard Zinn: How History Teachers Can Help Students Think Outside the Box

We are pleased to share the keynote address Howard Zinn gave at the 2008 National Conference for the Social Studies (NCSS) conference. He offers clear examples of how history teachers can help students think outside of the box. This is an excellent film to be shown in parts or in full for staff discussion.

Teachers on the Value of Teaching People’s History

Since the launch of the Zinn Education Project in 2008, we have received hundreds of comments from teachers about the value of “a people’s history” and how they are incorporating it in their classroom. Here are a few of those comments:

A long list of “good guys” with no one to struggle with is neither a true story nor a good story. It doesn’t resonate because it leads the student to believe that we are all waiting for the next exceptional leader, instead of becoming a force for change in our own communities. A People’s History helped me recognize this as a student of history and inspires my attempt to bring true stories to young people, weary of the inaccessible lists that history teaching has become.

—Reynolds Bodenhamer, 11th-Grade U.S. History, Gulfport, Miss.

READ MORE▸ Teacher Comments

Zinn’s work offers an alternative perspective that students need in order to think more critically about key issues in history.

—William Thomas, Auburn, N.H.

Knowing that resources like the Zinn Education Project exist make me feel so hopeful about the network of people who are engaged in this kind of dialogue with their students. I am a young, white female living in Baltimore and teaching at an all black middle school. These resources are so valuable to me personally and to the relationships being built between the students and the faculty. Thank you to everyone involved in keeping this collaboration evolving!

—Lara Emerling, Middle School Teacher, Baltimore, Md.

Thank you so very much for sharing Zinn’s materials with us. We badly need to get a message of advocacy and action into our communities and into our hearts. Your support makes this easier, in a fight that feels overwhelming …

—Nancy Jean Smith, California State University Stanislaus, Stockton, Calif.

…[I]t was my sense that throughout the year last school year, and so far this school year, [that] the kids responded well to the Zinn book … [because] they appreciate Zinn’s perspective. I think most of the kids realize that there has been something seriously flawed with the way in which U.S. history has been presented to them, and Zinn’s book, for many of them, verifies this feeling. Even the kids who don’t agree with Zinn’s take on US history appreciate the fact that he has a definite approach to history and the kids say that a strong perspective makes the text more engaging than traditional history texts. Also, the students enjoy his narrative style where one topic or series of events is dealt with in a clean, short chapter, as opposed to a traditional textbook’s reliance on sections that seem to drone on with facts layered on more facts. We will see how this year continues.”

—Nick Caltagirone, High School Teacher, West Chicago, Ill.

Read more teacher comments

Historians and Authors

If we don’t learn that it was people just like us — our mothers, our uncles, our classmates, our clergy — who made and sustained the modern Civil Rights Movement, then we won’t know we can do it again.

If we don’t learn that it was people just like us — our mothers, our uncles, our classmates, our clergy — who made and sustained the modern Civil Rights Movement, then we won’t know we can do it again.

—Judy Richardson, co-editor of Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts By Women in SNCC

READ MORE▸ Judy Richardson

Judy Richardson, co-editor of Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts By Women in SNCC

Back in 1978, when we first started production on what later became the 14-hour Eyes on the Prize series, everything — films, books, curricula — revolved around Dr. King. Times have changed somewhat, but not as much as I would have assumed. The wonderful new local movement scholarship that has examined activism in southern communities big and small somehow hasn’t “trickled down” beyond the upper reaches of academia the way it rightfully should have.

The problem with this singular focus on Dr. King isn’t just that it’s ahistorical. Even more insidious, by focusing only on the greatness of Dr. King, we ignore the amazing courage, strength and brilliant leadership of regular folks, particularly Black folks in the Deep South like Fannie Lou Hamer, Hartman Turnbow, Fred Shuttlesworth, Charles and Henrietta Moore (and we should never forget one of the Movement’s foremost strategists, Ella Baker). It was they who had been plowing the ground of political and social change even before the heightened activism of the 1960s, and it was they who were often killed — or destroyed in other ways — before they could even see the fruits of the seeds they’d sown.

By focusing only on a few “special” people like Dr. King and Rosa Parks — rather than highlighting, as Howard Zinn did, the stories of “ordinary” heroines and heroes — we fail to understand that most activists in the movement didn’t consider themselves “special” at all. They were simply people who chose to change things — chose to risk their lives, their livelihoods and possibly their personal dreams for the future to right the wrongs they could no longer ignore. Also important to students: many of those who were at the cutting edge of this change were young people. It is through the vanguard of the young activists of the 1960s that students will, hopefully, see themselves as the activists of today.

If we don’t learn that it was people just like us — our mothers, our uncles, our classmates, our clergy — who made and sustained the modern Civil Rights Movement, then we won’t know we can do it again. And then the other side wins — even before we ever begin the fight.

Expanding ethnic diversity of this century, a time when we will all be minorities, offers us an invitation to create a larger memory of who we are as Americans and to re-affirm our founding principle of equality.

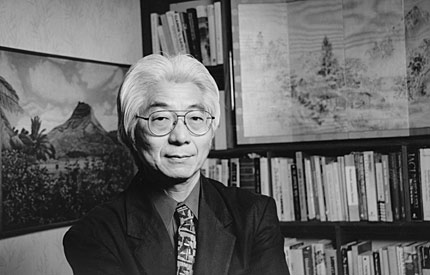

—Ronald Takaki (1939 – 2009), author of A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America

READ MORE▸ Ronald Takaki

Let me tell you what I have been striving to do as a teacher and scholar. I noted the power and pervasiveness of the master narrative of American history, which defines American as white. We have an opportunity at the beginning of this 21st century to challenge this narrative and to re-vision our nation’s history. How can diverse Americans become “one people”? I believe that one path is for us to pursue [a] study of the past that includes all of us, making all of us feel connected to one another as “we the people,” working and living in a nation, founded and “dedicated” (to use Lincoln’s language) to the “proposition” that “all men are created equal.” So, our expanding ethnic diversity of this century, a time when we will all be minorities, offers us an invitation to create a larger memory of who we are as Americans and to re-affirm our founding principle of equality. Let’s put aside fears of the “disuniting of America” and warnings of the “clash of civilizations.” As Langston Hughes sang, “Let America be America, where equality is in the air we breathe.”

In the telling of history, however, the genesis of leadership is easily forgotten. Textbook authors and popular history writers fail to portray the great masses of humanity as active players, agents on their own behalf.

In the telling of history, however, the genesis of leadership is easily forgotten. Textbook authors and popular history writers fail to portray the great masses of humanity as active players, agents on their own behalf.

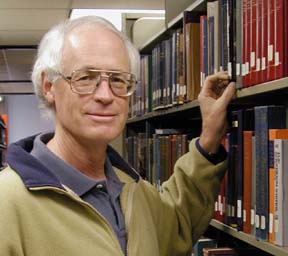

—Ray Raphael, from the teaching activity “Re-examining the Revolution,” author of A People’s History of the American Revolution

READ MORE▸ Ray Raphael

Ray Raphael, from the teaching activity “Re-examining the Revolution,” author of A People’s History of the American Revolution

In textbooks students learn that a handful of celebrated personalities make things happen, the rest only tag along; a few write the scripts, the rest just deliver their lines. This turns history on its head. In reality, so-called leaders emerge from the people — they gain influence by expressing views that others espouse.

In the telling of history, however, the genesis of leadership is easily forgotten. Textbook authors and popular history writers fail to portray the great mass[es] of humanity as active players, agents on their own behalf. Supposedly, only leaders function as agents of history. They provide the motive force; without them, nothing would happen. The famous Founders, we are told, made the American Revolution. They dreamt up the ideas, spoke and wrote incessantly, and finally convinced others to follow their lead. But in trickle-down history, as in trickle-down economics, the concerns of the people at the bottom are supposed to be addressed by mysterious processes that cannot be delineated. What happens at the top is all that really counts. This distorts the very nature of the historical process, which must, by definition, include masses of people.

The way we learn about the birth of our nation is a case in point. If we teach our students that a few special people forged American freedom, we misrepresent, and even contradict, the spirit of the American Revolution. Our country owes its existence to the political activities of groups of dedicated patriots who acted in concert. Throughout the rebellious colonies, citizens organized themselves into an array of local committees, congresses, and militia units that unseated British authority and assumed the reins of government. These revolutionary efforts could serve as models for the collective, political participation of ordinary citizens. Stories that focus on these models would confirm the original meaning of American patriotism: Government must be based on the will of the people. They would also show some of the dangers inherent in majoritarian democracy: the suppression of dissent and the use of jingoism to mobilize support and secure power. They would reflect what really happened, and they would reveal rather than conceal the dynamics of political struggle.