On November 13, 1953, during the height of the McCarthy era, Robin Hood and his band of “merry outlaws” made headlines. Mrs. Thomas J. White of the Indiana Textbook Commission called for a ban of Robin Hood in all school books for promoting communism because he stole from the rich to give to the poor. As a Republican member of the commission, Mrs. Thomas J. White (who is never referenced by her first name) defended her position by stating that “there is a Communist directive in education now to stress the story of Robin Hood. They want to stress it because he robbed the rich and gave it to the poor. That’s the Communist line. It’s just a smearing of law and order and anything that disrupts law and order is their meat.”

On November 13, 1953, during the height of the McCarthy era, Robin Hood and his band of “merry outlaws” made headlines. Mrs. Thomas J. White of the Indiana Textbook Commission called for a ban of Robin Hood in all school books for promoting communism because he stole from the rich to give to the poor. As a Republican member of the commission, Mrs. Thomas J. White (who is never referenced by her first name) defended her position by stating that “there is a Communist directive in education now to stress the story of Robin Hood. They want to stress it because he robbed the rich and gave it to the poor. That’s the Communist line. It’s just a smearing of law and order and anything that disrupts law and order is their meat.”

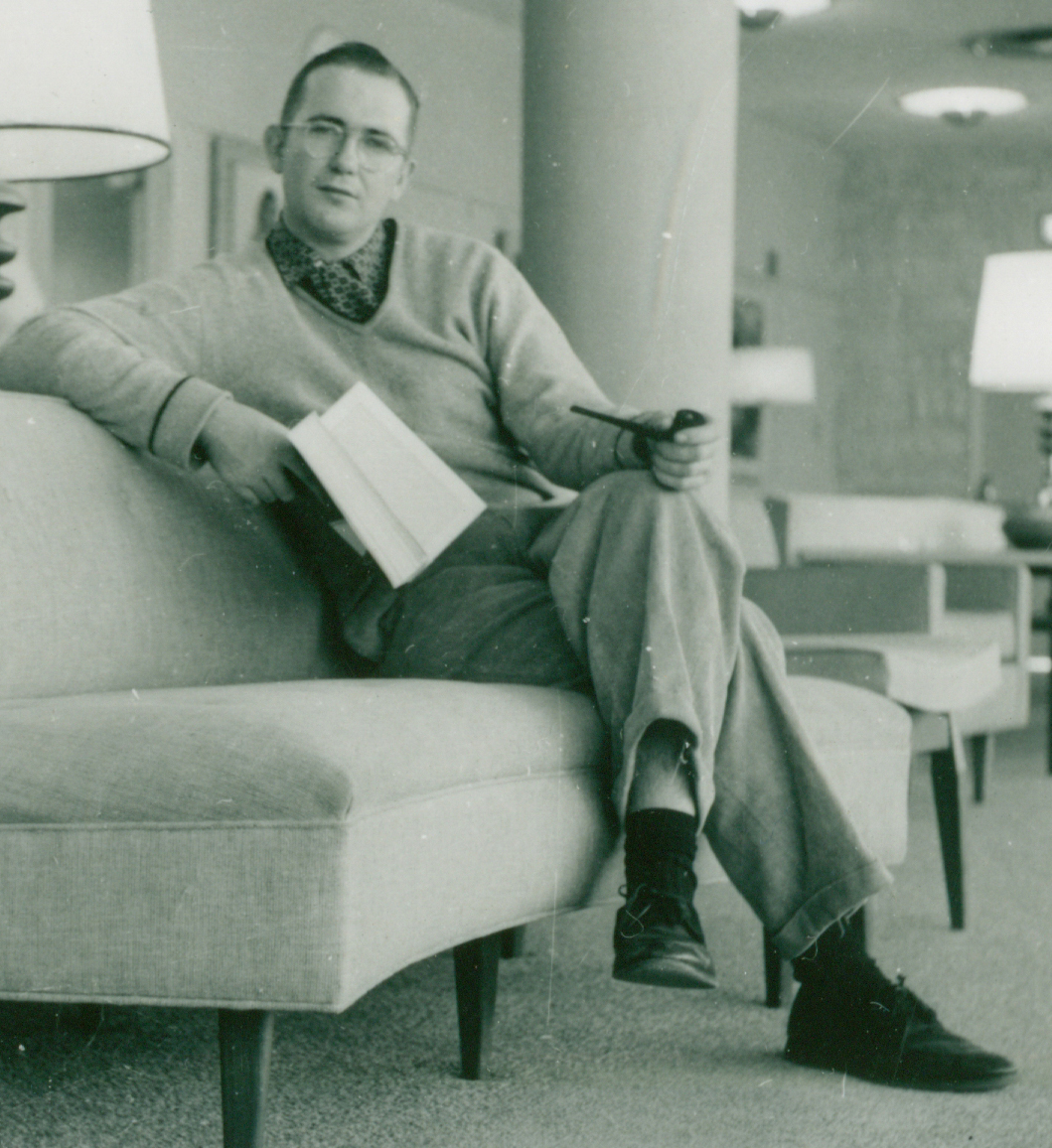

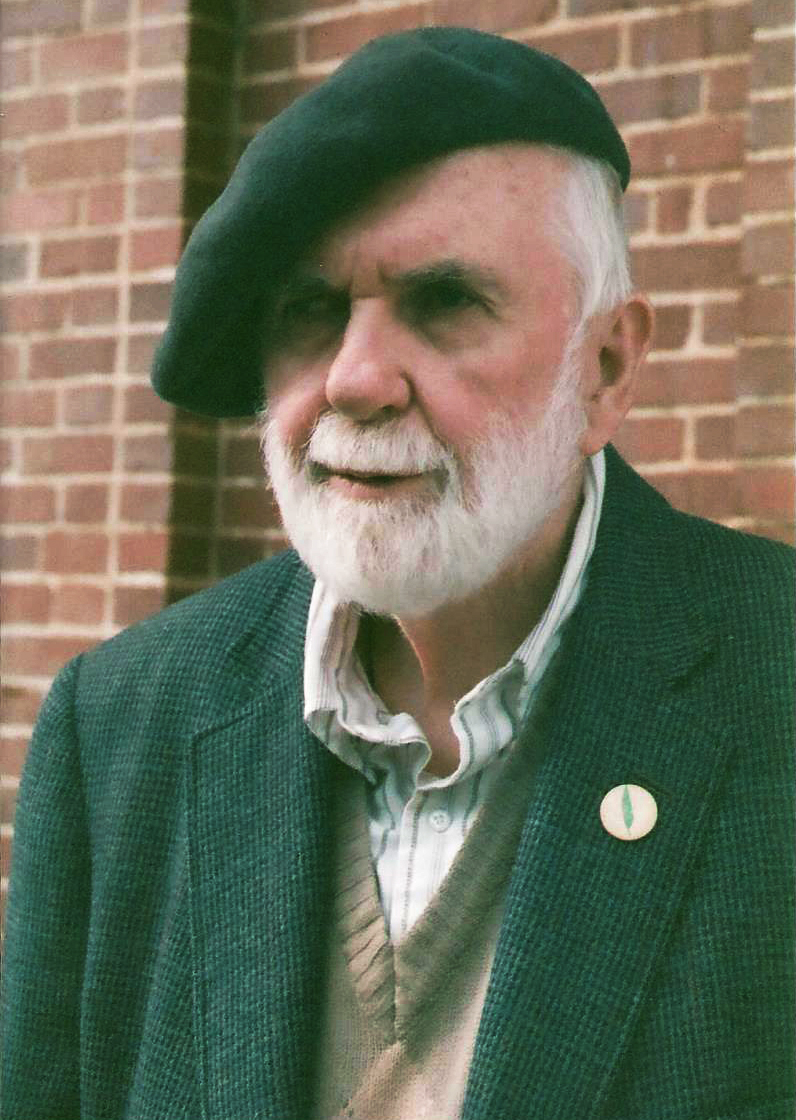

Bernard Bray, then (above) and now (right). Bray was one of the five students who started the Green Feather Movement.

Bernard Bray, then (above) and now (right). Bray was one of the five students who started the Green Feather Movement.

In response to Mrs. White’s attempts at censorship, as well as the larger McCarthy witch hunt it was part of, five students from Indiana University at Bloomington (IU) started the Green Feather Movement. The IU students — Bernard Bray, Mary Dawson, Edwin Napier, Blas Davila, and Jeanine Carter — went to a local poultry farm and collected six large burlap sacks filled with chicken feathers and took them to the basement of a nearby house where they dyed them green to represent the one worn by Robin Hood. On March 1, 1954, the students spread them throughout campus to protest censorship. Their activism was quite radical when viewed within the political climate of the time, when IU freshmen and sophomore men were still required to participate in ROTC and, according to a January 1954 Gallup poll, 50 percent of the country supported McCarthyism. The students were allegedly investigated by the FBI and disparaged in the local newspaper.

Although some faculty refused to comment on the movement for fear of retribution, the psychology department lent lukewarm support, providing some administrative protection. Nevertheless, in May 1954, IU President Herman B. Wells and the student senate denied the Green Feather Movement’s request for official recognition because they were deemed too political.

Bernard Bray’s parents. Their religious convictions influenced Bernard growing up.

The students’ motivation to act was not only fueled by the Red Scare, but also by their faith.

In an exclusive interview with the Zinn Education Project, Bernard Bray described how he and his friends met weekly with the Roger Williams Fellowship at the First Baptist Church in Bloomington where they would discuss the burning social issues of the day while sharing a meal and performing vespers. Bray explained the importance of these meetings by saying that “my sort of spirituality was a . . . struggle to find a way to make God’s will become a reality in my life and to that working in fellowship with others and the Roger Williams Fellowship was the ideal context for doing that.” He also noted the influence of a seminarian he knew growing up who was jailed for his refusal to participate in World War II, as well as the religious convictions of his own parents, Helen and Earl Bray, who stood up and walked out of their church after someone made a racist comment about a Japanese American.

The Green Feather Movement inspired solidarity actions on campuses throughout the country, illustrating the power of student activism. News of the IU movement was publicized in both local and college newspapers throughout the country as well as The Young Socialist Challenge, the bulletin of the Young People’s Socialist League. Members of the Labor Youth League (LYL), an offshoot of the Young Communist League USA, distributed small white pins picturing a green feather as a sign of solidarity. Green Feather groups subsequently spread to the universities of Harvard, Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Chicago, and Purdue.

At the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), students planned to march in support of the Green Feather Movement. Unfortunately, the pins they ordered for the march did not reach them in time. Instead, similar to the IU group, they went to the local poultry shop to purchase feathers and dyed them green. Green feathers were spread throughout campus during the march, which featured a crier dressed as Robin Hood followed by 200 students dressed as his Merry Men. As Matthew Allan Ides notes in his 2009 dissertation, “Cruising for Community: Youth Culture and Politics in Los Angeles, 1910-1970”:

The Green Feather movement at UCLA was a turning point in student activism on campus because this type of political performance was not sanctioned by the administration.

In dressing for the event, youth activists tested the waters of the counterculture and for the moment put aside reservation of appearing to conform. Second, the organizing for this event connected local struggles to a national organization, thereby harmonizing the practices of youth activism.

Many students continued to wear the movement’s pins and feathers after the initial events, and to those in the know this practice revealed networks of youth solidarity. Although the LYL played a role in organizing the Green Feather Movement on campus, the GFM pointed to a new brand of youth activism that would fully develop in the 1960s.

Thankfully the attempt to censor Robin Hood failed. News of these attempts even crossed the Atlantic, where residents of Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire, England, the traditional home of Robin Hood, mocked the association of him with communism. When asked why attempts to censor Robin Hood pushed Bray to action, he explained that the issue wasn’t Robin Hood as much as “a great opportunity to find a symbol to fight McCarthyism — it was more a matter of principle.” Although the Green Feather Movement lasted less than a year and concluded more than 50 years ago, we are still confronted with the same kinds of censorship in communities throughout the United States today.

These displays of activism and solidarity were important challenges to the abusive power of McCarthyism. As students and teachers are faced with attempts to censor people’s history, the Green Feather Movement inspires us to support the right to teach outside the textbook.

By Alison Kysia. Kysia has taught history at Northern Virginia Community College-Alexandria. She was a Zinn Education Project Fellow in 2013 and project director of “Islamophobia: a people’s history teaching guide” at Teaching for Change starting in 2018.

Get students involved in researching the Green Feather Movement!

Students can contribute to a people’s history of the Green Feather Movement by adding their research to our online archive. Here are a few potential leads:

1) There is an archive about the Green Feather Movement at the Indiana Historical Society (phone number: 317-234-0321). We verified that a deposit was made in 2011 by Jean Perney (at whose home the green feathers were dyed), but as of this posting, it has not been processed.

Students can follow up on this important lead by asking if the archive processing can be expedited, and then investigate the contents of it. We are particularly interested in obtaining high-quality photographs, photocopies, and PDFs of the contents of the archive.

2) Some news articles suggest that there was an FBI file opened on the Green Feather Movement. Students can file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, on both the movement and the individual members and report on their findings.

3) There were a number of newspaper articles written about the Green Feather Movement. Students can research the records of two local newspapers: the Bloomington Herald-Telephone; and the Indiana Daily Student newspaper (some references suggest that there were daily reports in this paper about the movement — in particular a letter to the editor, possibly on May 21, 1954, from the — Executive Council of the Green Feathers”).

4) Students can conduct an oral history interview of a close associate of the Green Feather Movement who still lives in Bloomington, Indiana. Contact us for more information about setting up that interview.

Sources

- Brian Janosch, “Ruffled Feathers: In an era intimidated by red, a group of students saw green,” Indiana

Daily Student, Mar. 2, 2005, accessed Oct. 15, 2013. - “Green Feather’ Asks Recognition,” The Harvard Crimson, May 21, 1954, accessed Oct. 15, 2013.

- “Green Feather Movement to Fight McCarthyism Will Start Here Soon,” The Harvard Crimson, May 11, 1954, accessed Oct 15, 2013.

- John Branigin, “What Did It Matter: The Legacy of Protest,” Indiana Alumni Magazine, March-April

2001. Download article here. - Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (Basic

Books, 1987), p. 63. - Matthew Allan Ides, “Cruising for Community: Youth Culture and Politics in Los Angeles, 1910-1970”

(PhD. Diss., University of Michigan, 2009, pp. 224-225), accessed Oct. 15, 2013. - Paul Buhle, “A People’s History of Robin Hood, ” YES Magazine, accessed Oct. 15, 2013.

- Betty Mae Shear,”Our Beginnings, Our Purpose, Our People, Our Future,” Roger Williams Fellowship, accessed Oct. 15, 2013.

- The Robin Hood Project at the University of Rochester, accessed Oct. 10, 2013.

- “Sherwood Forest Laughs,” The New York Times, Nov. 13, 1954.

- “Indiana Censor Fears Little Red Robin Hood,” The New York Times, Nov. 14, 1953.

- Classroom resources on McCarthyism at the Zinn Education Project.

New Reference

The Green Feather Movement via IU History, Pride & Tradition, August 1, 2019

We welcome more stories about the Green Feather Movement. Please send any information (text or images) you have to the Zinn Education Project. The Green Feather Movement would be a wonderful topic for student research.

So glad to hear about this. Censorship is frightening.

The son of Rev Doug Rae, also named Doug, was beaten up at his high school when his father’s role in the Green Feather Movement was revealed in a local paper.

(He told me this years later).