By Larry Miller

As a U.S. history teacher, I taught high school students that resistance to slavery was pervasive. Whether it was the open rebellion of Nat Turner, the Denmark Vesey conspiracy, the battle of the Negro Fort, the publication of Walker’s Appeal, the Underground Railroad or the daily acts of resistance that included work stoppages, slowdowns, and slow poisoning of plantation owners’ families, people living in slavery repeatedly demonstrated opposition to the slave system, sometimes at great cost. None of this is evident in Quentin Tarantino’s movie, Django Unchained. Instead, the movie reinforces just about every stereotype I tried to challenge in my history classes.

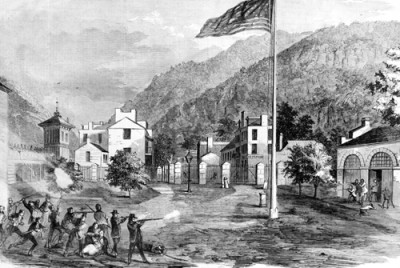

Raid on Harpers Ferry, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1859.

Django begins in 1858 and flows into 1859 and possibly beyond. 1859 happens to be the year of the John Brown-led attack on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, an action that was intended by this section of the abolitionist movement to launch an uprising that would lead to the end of slavery. The rebellion did not take place in isolation but was nurtured by a growing anti-slavery movement throughout the United States and its territories.

Tarantino’s depiction of these years shows no resistance to slavery. Enslaved people in Django are compliant, the abolition movement utterly invisible. Instead, the “resistance” presented in the film is generated either by the white bounty hunter, Schultz, or by the formerly enslaved Django once he gains a sense of power in the shadow of Schultz. The movie brings Django and Schultz together with the goal of capturing three slave overseers from Django’s past who are also wanted for murdering whites. Django agrees to help Schultz collect the bounty on these three, and Schultz will then help Django free his wife, who is being held on a Mississippi plantation called Candieland.

I did not have high expectations before seeing Django. I’ve been dismayed by Tarantino’s fetish with violent special effects, and especially by his blatant racism, for example, depictions of Mexicans as lizard-like vampires in From Dusk till Dawn. But Django was even worse than I expected. I have heard defenses of Tarantino that include, “. . . he can’t be racist, he had a black stepfather. He had black girlfriends.” Whatever his experience or intentions, the movie was ahistorical and racist.

Tarantino attempts to disarm the viewer with cartoonish street humor that reminded me of Blazing Saddles. For example, when Django is told by Schultz he can pick the clothes he wishes to wear, he chooses a powder blue satin Little Lord Fauntleroy suit, a pimp-like outfit that could have been worn in the court of Marie Antoinette.

The 109 uses of the N-word is supposed to invest this depiction of the antebellum South with reality. It doesn’t. In big and little ways, Django mangles the history. The movie opens by telling viewers that it takes place in 1858, two years before the Civil War. Of course, the Civil War began in 1861, not 1860, but it doesn’t really matter, because the film contains nothing that makes the date even slightly meaningful. In one scene, vigilantes wear Ku Klux Klan-like hoods. However, there was no need for anyone to wear a hood at a time when rape, murder, brutality, and capturing runaway slaves were all perfectly legal, and anti-slave militias were institutionalized. In fact, there was no KKK until after the Civil War.

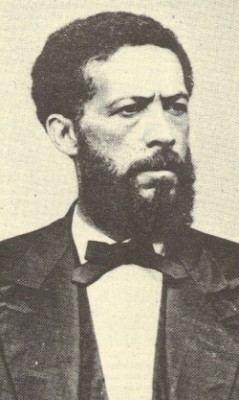

John Mercer Langston, abolitionist. Click image for a lesson on the people’s history of the abolition movement.

Another hallmark of Tarantino’s movie is the fear in the lowered eyes of African Americans, refusing to make eye contact with whites. They fail to resist even when Django kills the overseers from a mining company and leaves open the door of the slave transport cage. The men sit motionless watching Django ride into the horizon back to the Mississippi plantation, not to lead a slave rebellion, but to free his wife and take revenge on that single plantation.

No doubt, Tarantino depicts brutality toward African Americans on the screen. But in an attempt to portray the psychology of the slave owner and slave society, Tarantino bores the viewer with empty dialogue that dominates long sections of the movie. Tarantino has nothing intelligent to say about the psychological underpinnings of white supremacy.

Tarantino does not spare the gore. He seems to have a fetish with presenting blood and flesh. Evidently, he is attempting some symbolism with the splattering of red blood on the white cotton growing in the field, on the white mane of a horse, and on the white walls of a plantation parlor. Yeah, we get it. But the result is to draw attention to itself rather than to connect the viewer with the institution of slavery. It’s a diversion. Tarantino cares lots more about special effects than he does the human resistance to suffering and oppression.

Don’t get me wrong. The slave owners, the slave profiteers, and the slave system merited fierce reprisals. But the goal of the slaves and the abolition movement was not revenge, but to end the slave system and all that it represented. In Django, violence is an end in itself, not a means to an end.

There is one person the viewer comes to hate more than anyone, even more than Candie, the sadistic slave master. This is Stephen, the slave master’s always-fawning head house slave, played by Samuel L. Jackson. This guy is truly subservient. But here, too, Tarantino relies on — and deepens — the stereotype of the slave who lives to serve his master. In my history classes, I wanted my students to understand that there was a duality to the role of house slaves. In fact, there are many instances recorded of plantation owners’ sense of betrayal when their supposedly loyal house servants fled to Union lines and freedom at the first possible opportunity during the Civil War. In the real world, so-called house slaves could be both obedient and long for liberty. But in Django Unchained, the Samuel L. Jackson character shows no such duality. He is simply a despicable, malicious person, loving his master’s very existence.

Enslaved African American women in the film play largely to two stereotypes: the mammy and the sexual temptress. One exception might be Kerry Washington’s character, Brunhilde, as Django’s wife, who was tortured for attempting to escape. But even she can be rescued only by the singularly rebellious Django.

Black women on the plantation are simply subservient — as food servers, cooks, cotton-pickers, or whipping victims. Black women in the brothels, like Candie’s apparent mistress Sheba, seem to love their oppressor. The same is true of Coco, wearing a French maid’s mini-dress, high heels and a large white bow in the front of her hair, answering to the Southern aristocrats’ every whim. Tarantino fails to present any strong black woman.

Spoiler alert. At the end of the movie, after Django kills the remaining slave-owning family members and overseers, he and his wife ride into the moonlight from deep within Mississippi. This is at a time when the slavocracy was at the height of being alarmed and armed, the year that fear of slave rebellion was rampant among plantation owners throughout the South. This meant that in every Southern state, expansion of militias and arming of white communities was pervasive. Any black woman or black man openly traveling the roads in Mississippi, Texas, or the Border States at that time would have been arrested or killed.

Only the underground systems, created from plantation to plantation by slaves and free blacks, and supported by black and white abolitionists in the North, would have allowed Django and his wife to escape. Tarantino relies on the individual hero to replace a movement of resistance.

My fear is that Tarantino’s fetishes, stereotypes, and contempt for actual history will become nestled in the popular culture as a legitimate depiction of the Black Holocaust. We need representations not to be cartoonish, but complex and accurate.

Today’s young people need sophisticated analysis of slavery — and how its legacy is experienced in contemporary America, where more black men are behind bars or under the watch of the criminal justice system than were enslaved in 1850, and more African American men are disenfranchised because of felon disenfranchisement laws than in 1870.

In a time where activism and resistance to oppression is as essential as it was in 1859, the demand for justice and equality must find expression in schools. The work of social movements and the demands of the many must be heard. They were not in Django Unchained. In the course of creating a free and just world, historical truth must be woven into popular culture, into the school curriculum, and into the consciousness of young people.

—by Larry Miller, an editor of Rethinking Schools Magazine and an elected member of the school board in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He is a former high school social studies teacher. Miller co-edited Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol. 2 and wrote “Lessons in Solidarity: Grady Hospital Workers United.”

Here are recommended resources for teaching outside the textbook about the abolition movement and the history of slavery in the United States.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn