The following description is from a review of Silver Rights by Paul Trachtman in the Smithsonian magazine, June 1997.

The following description is from a review of Silver Rights by Paul Trachtman in the Smithsonian magazine, June 1997.

Silver Rights [is the] riveting memoir of one African-American family’s fight to send their children to the segregated white schools of Drew, Mississippi.

The author, Constance Curry, was a field representative of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) who tried to help the Carter family live through its ordeal of intimidation, reprisals and insults as seven of its children became the only Black students in Drew’s white elementary and high schools in 1965. (An eighth would join them in 1967.)

The voices in the book are mostly those of the Carters, through Curry’s interviews and the many letters Mae Bertha Carter wrote to the Friends’ headquarters as one crisis followed another. As a result, the book has an immediacy, intimacy and emotional truth that history rarely reveals. It also unfolds with a simplicity of words and facts that make the Carters’ courage, faith and love a reality any reader can share. Even the title of the book is a reflection of that language. Among the rural Black families of the Mississippi Delta, the bureaucratic term “civil rights” was translated as the dream of “silver rights.”

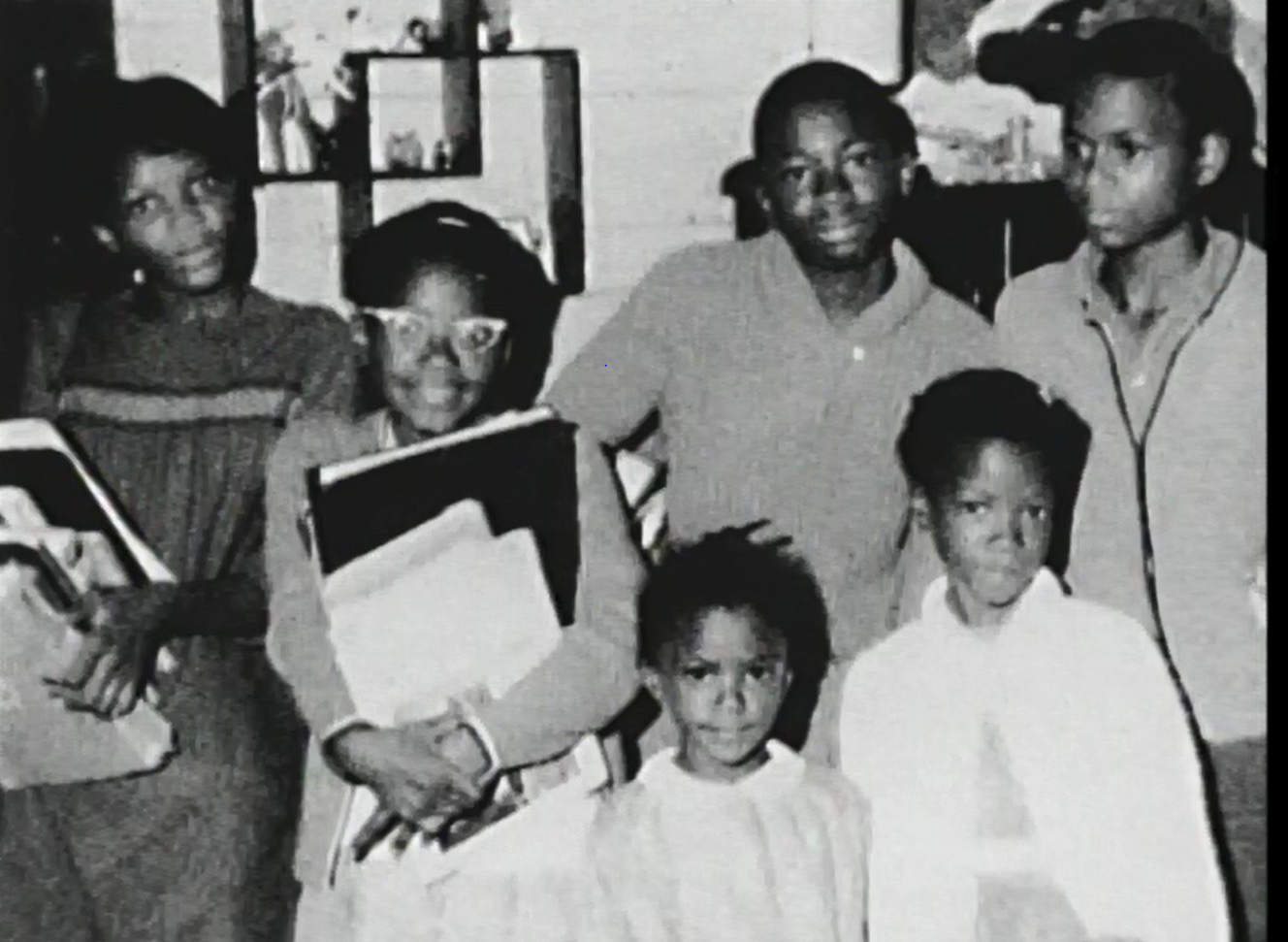

Mae Bertha Carter.

To tell this story, Curry spent the past few years renewing her friendship with the Carters, interviewing the grown children, trying to set the events of the 1960s in perspective. The Carters were a sharecropping family on a cotton plantation outside of Drew when Mississippi, under threat of losing federal funds, came up with a “freedom of choice” plan to circumvent federal law. Families like the Carters could sign papers to send their children to all-white schools, but both Blacks and whites knew what would happen to families who made that choice. “If they don’t get you in the wash, they’ll get you in the rinse,” Mae Bertha Carter told a visiting minister from Ohio who supported the family.

The Carters were threatened with eviction, and found credit in local stores cut off and their home shattered by gunshots in the dark, forcing them to sleep on the floor in fear. Spitballs and insults rained on the children as they rode the bus to a school where life was no easier. “I hated history class,” one of the older boys recalled, “when we covered the Civil War and the teacher said ‘nigger’ and allowed the students to say it like I wasn’t even there.”

It was the Carter children who made the choice to go to the white schools. None of them ever went back to the black schools, which had split sessions so that students could work in the cotton fields. “What I hated most was being in the cotton field and seeing the white school buses pass us by while we were picking,” the oldest girl, Ruth, recalled. But Ruth also came to hate her days at the white school.

During that time, it seemed like I was filled up with hate. I hated Mississippi, I hated the white man. I hated my teachers. I hated everything. Then we started having these little sessions at home in the afternoon after school. It was almost like therapy. We would sit down and Mama would say, ‘How did things go today at school?’ We would talk about what happened and a lot of times we would cry together. . . .

As Ruth reconstructed those afternoons, it was her mother’s voice she heard reverberating in her memory. “If Mama heard me say, ‘I hate white people, I just can’t stand them,’ she always answered, ‘Don’t you ever say that. Don’t you ever say that you hate white people or anyone — it’s not right.’ . . . The other thing she wouldn’t let us say was that we wished we had never been born.”

Nevertheless, the pressures on the children were brutal indeed. The youngest, Carl, who entered the first grade in 1967, recalled the weight of isolation. The next year, in the second grade, he simply tried to flee.

Not having any playmates . . . made me feel bad. . . . I just left the schoolyard one day and came home. I was only seven . . . I told Mama that I had walked all the way home and I wasn’t going back. I said I was sick, got in bed.

But the next day he was back, his main refuge being his excellence as a math student.

Mae Bertha and her husband, Matthew, guided their children through the worst days with a courage and faith that was the heart of the civil rights movement, but they could not have done it alone. Through civil rights workers like Constance Curry, word was spread, and people of goodwill in many places became sources of support for the Carters.

Here, for instance, is what happened when the overseer ploughed under the Carters’ cotton crop before they could pick it:

Even with no money from the cotton crop, the Carters were able to survive November and December. Amzie Moore [a Black veteran who had come home and helped organize a local NAACP branch] brought food, the Boulder Friends [in Colorado] continued to send lunch money, the AFSC sent small grants, the Morningside Gardens Civil Rights Committee in New York City contributed clothing and money, and some canned foods came from a church in New Jersey. And on the day when the overseer did not show up with the family’s customary $15 for their car’s annual license plate fee, Fannie Lou Hamer, by then a leader in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, brought Mae Bertha the tag money.

Reading this book is a reminder of the deep interconnectedness of our lives, of the power of conscience when people care about and for each other, and are willing to act with love against the force of hatred and violence. Seven of the eight Carter children who desegregated the schools of Drew later graduated from the University of Mississippi, where the first Black student to enroll needed an escort of U.S. marshals. The spirit that sustained them was expressed in a letter from Mae Bertha to Constance Curry in May 1966:

I went to church on Sunday and my preacher preach about love one another — it don’t mean Negro only — it means everybody, white and Black.

[As noted above, this description of the book is by Paul Trachtman.]ISBN: 9780156004794 | Mariner Books

Related Resources

The Intolerable Burden: Award-winning 56-minute film documentary about the Carter family’s struggle to desegregate Drew schools. Produced in 2003 by Chea Prince and Constance Curry. Icarus Films. “One of the best video histories of the desegregation era ever produced. An excellent example of how documentaries on the 1960s should be done. Captures on film what it means to be a courageous individual. The magisterial clarity with which this dramatic story… is told keeps the viewer’s attention throughout. Indispensable to students. . . because the actual participants take center stage — one would be hard pressed to find this caliber of work in any other single story of this era.” —Professor Curtis Austin, University of Southern Mississippi

The Intolerable Burden: Award-winning 56-minute film documentary about the Carter family’s struggle to desegregate Drew schools. Produced in 2003 by Chea Prince and Constance Curry. Icarus Films. “One of the best video histories of the desegregation era ever produced. An excellent example of how documentaries on the 1960s should be done. Captures on film what it means to be a courageous individual. The magisterial clarity with which this dramatic story… is told keeps the viewer’s attention throughout. Indispensable to students. . . because the actual participants take center stage — one would be hard pressed to find this caliber of work in any other single story of this era.” —Professor Curtis Austin, University of Southern Mississippi

This School is Not White!: An elementary school picture book, by Doreen Rappaport and illustrated by Curtis James, about the Carter family’s struggle to desegregate Drew schools. (Jump at the Sun, 32 pages, 2005.)

This School is Not White!: An elementary school picture book, by Doreen Rappaport and illustrated by Curtis James, about the Carter family’s struggle to desegregate Drew schools. (Jump at the Sun, 32 pages, 2005.)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn