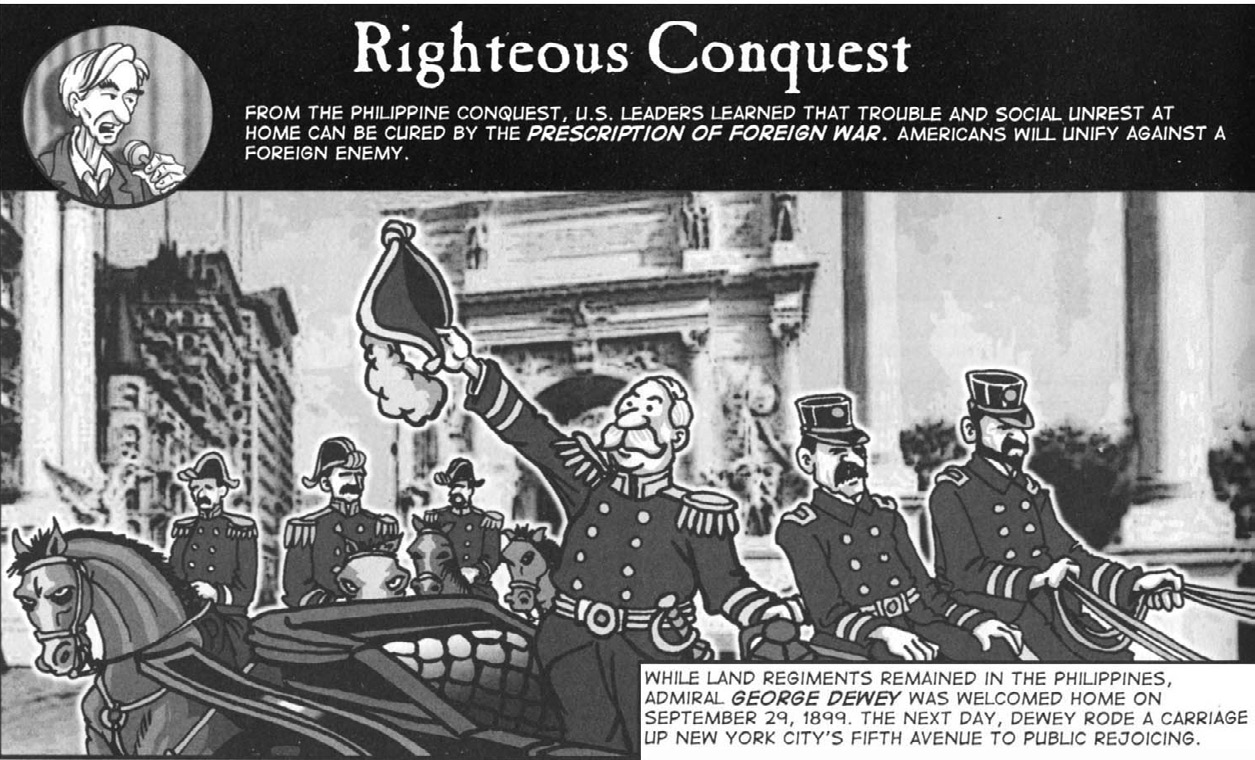

Anti-bullying curricula are the rage these days. But as teachers endeavor to build a culture of civility among young people in school, the official history curriculum they are provided often celebrates, or at least excuses, bullying among nations. Well, at least when the United States is the bully.

A good example is the U.S. invasion of Grenada — Operation Urgent Fury, as it was called by the Reagan administration — launched exactly 30 years ago this week, on Oct. 25, 1983. Grenada made an unlikely target of U.S. military might. Its main product was not oil but nutmeg. Its naval fleet consisted of about 10 fishing trawlers. Grenada’s population of 110,000 was smaller than Peoria, Illinois. At the time of the invasion, there was not a single stoplight in the entire country. So what put Grenada in the crosshairs of the Reagan administration?

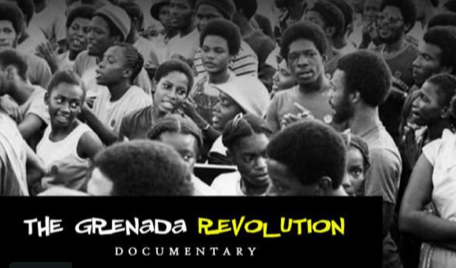

In 1979, the socialist New Jewel Movement had overthrown the corrupt and unpopular dictator Eric Gairy in an almost bloodless coup. For years, Gairy ruled through fear. His secret police, the “Mongoose Gang,” had been supplied by the U.S.-backed Pinochet dictatorship in Chile. The revolution launched by the New Jewel Movement — the “Revo,” as it was affectionately dubbed — was immensely popular. By 1982, when I first visited the island, a literacy campaign was under way, new schools had been built, and unemployed youth in the countryside benefited from new agricultural cooperatives. Grenada welcomed Cuban aid: teachers, health professionals, and construction workers on the new international airport who aimed to replace the antiquated and dangerous airstrip up in the mountains. In just four years, unemployment was cut from 49 percent to 14 percent. Instead of advertising cigarettes and booze, colorful billboards throughout the island promoted education: “Each One Teach One,” “If You Know, Teach; If You Don’t, Learn,” and “Education Is Production, Too.”

Grenada’s ‘threat’

On a steamy August night, with hundreds of other Grenadians I squeezed into a high school auditorium in Grenada’s capital, St. George’s, to watch musical and theater performances from throughout the Caribbean — Dominica, Barbados, and St. Vincent. Each group closed its act with a short speech on how inspiring they found the changes in Grenada. With shouts and smiles they pledged to return to their islands and spread the word about the Grenadian Revo. This West Indian cultural evening exemplified Grenada’s real “threat” — not a launchpad for invasion, but a socialist-inspired revolution with a reggae beat that sparked imaginations throughout the Caribbean. To use Noam Chomsky’s expression, Grenada was the threat of a good example.

A small island with a population of less than 110,000, Grenada was, as Noam Chomsky said, a threat of a good example.

The United States responded to developments in Grenada with hostility. In August 1981, more than two years before the actual U.S. invasion — in naval maneuvers called “Ocean Venture 81” — the United States staged a mock invasion of Grenada on the island of Vieques, Puerto Rico. Code-named “Amber and the Amberdines,” the supposedly fictitious eastern Caribbean country of Amber was accused of being a pawn of Country Red to “export terrorism to a number of Caribbean countries.” A Ranger battalion based in Fort Lewis, Washington, was airlifted to Vieques. Paratroopers landed in mountainous areas of the island and were backed by air attacks and the amphibious landing of thousands of marines. The obvious similarity between “Amber and the Amberdines” and Grenada and the Grenadines was a not-so-veiled threat. President Reagan claimed that Grenada’s construction of the international airport was a ruse for “Soviet-Cuban militarization” — this despite enthusiastic support for the airport from such un-radical entities as Grenada’s Chamber of Commerce, the Grenada Hotel Association, and the Employers’ Federation.

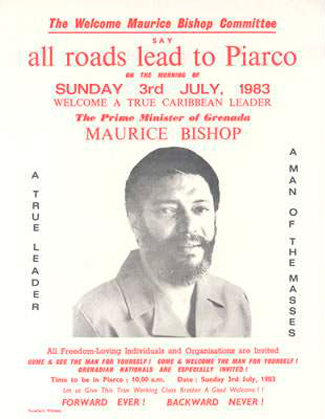

Then came October 1983. In the space of a few days, the leadership of the New Jewel Movement imploded. Grenada’s hugely popular prime minister, Maurice Bishop, was arrested by a faction of his own government and then executed along with many of his close associates. In massive demonstrations following Bishop’s arrest, the Grenadian army fired into the crowds. Shortly after, a military government was formed and announced a 24-hour shoot-to-kill curfew. This violence was the culmination of sectarian infighting whose origins are still murky — a flammable concoction of ambition, ideological rigidity, and leadership isolation, made more volatile by the ever-present threat of U.S. intervention.

Then came October 1983. In the space of a few days, the leadership of the New Jewel Movement imploded. Grenada’s hugely popular prime minister, Maurice Bishop, was arrested by a faction of his own government and then executed along with many of his close associates. In massive demonstrations following Bishop’s arrest, the Grenadian army fired into the crowds. Shortly after, a military government was formed and announced a 24-hour shoot-to-kill curfew. This violence was the culmination of sectarian infighting whose origins are still murky — a flammable concoction of ambition, ideological rigidity, and leadership isolation, made more volatile by the ever-present threat of U.S. intervention.

In the midst of these traumatic events the United States launched its invasion — sending 7,600 troops into the tiny island — mostly from the United States, but with some from Jamaica and other Caribbean nations. An equivalent force invading the United States would total more than 20 million soldiers. Ronald Reagan defended the invasion, saying Grenada “was a Soviet-Cuban colony being readied as a military bastion to export terror and undermine democracy. We got there just in time.” He also claimed that the invasion was intended to rescue the 800 U.S. medical students on the island, even though the medical school’s chancellor denounced the invasion and said it posed a greater risk to students than the turmoil then wracking the island.

By a vote of 108 to 9, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion as a “flagrant violation of international law.”

By a vote of 108 to 9, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the invasion as a “flagrant violation of international law.”

But that’s not how the Grenada invasion is remembered in today’s history curriculum. Mostly, it’s not remembered at all. A stack of U.S. and world history textbooks includes no mention of Grenada. Pearson/Prentice Hall’s United States History embeds its treatment of the invasion in a chapter on “The End of the Cold War,” which could have been written by a Reagan speechwriter. The chapter opens with a Reagan quote, framing the Cold War as a “struggle between right and wrong and good and evil.” A chapter subhead shouts “Reagan Challenges Communism.” By the time students encounter the Grenada invasion, they have been drenched in Cold War rationales. Here is the entire section on Grenada:

In 1983, Reagan acted to counter another perceived threat in the Western Hemisphere. Members of a radical leftist movement, with some help from Cuba, had violently ousted the Grenadian prime minister. On October 25, 1983, U.S. troops invaded Grenada to prevent the island nation from becoming a communist outpost and to protect the lives of American medical students. Even though the legal grounds for this invasion proved questionable, most Americans approved of Reagan’s decision.

President and Nancy Reagan at a memorial service for Lebanon and Grenada casualty victims, Nov. 4, 1983.

Passages like this in the corporate-sponsored curriculum normalize imperialism. This is not education, it’s stenography — texts offer students the U.S. justification for a military invasion of a sovereign nation without raising a single critical question. United States History presents nothing to support its assertions — there is not a shred of evidence, for example, that Cubans had anything to do with the overthrow and murder of Maurice Bishop — nor does the passage report any dissent, with the exception of the tepid “legal grounds for this invasion proved questionable.” The subtext here is that if U.S. policymakers “perceive” something to be a threat to “our” interests, then military action is legitimate. Especially if “most Americans approve.” As another widely used textbook, Holt McDougal’s The Americans, finishes its paragraph on Grenada: “Eighteen American soldiers died in the attack, but Reagan declared that the U.S. invasion had been necessary to defend U.S. security.” End of story.

In their obsequious approach to the invasion of Grenada, the corporate textbook writers follow the lead of the corporate media who did the original reporting on the invasion. As the operation began, the members of the media complained about their exclusion from the action. But as Glen Ford, author of The Big Lie: Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of the Grenada Invasion, said, once they were allowed to accompany U.S. troops, “they performed as if they were spokespersons for the U.S. military.” According to Ford, “There was not the slightest trace of independence whatsoever.” One correspondent called it “a lovely little war.”

To report on the U.S. occupation, I returned to Grenada 10 months after the invasion. Driving from the airport to St. George’s, the first thing I noticed was that the popular education billboards had been chopped down. And it wasn’t only these symbols of the Revo that had been eliminated. The U.S.-installed interim government had abolished the agency to aid cooperatives; eliminated the Centre for Popular Education, the literacy program; shuttered a government-owned agro-industries plant; and returned land from farmers’ cooperatives to absentee owners.

Unless teachers “teach outside the textbook,” as the Zinn Education Project urges, students will learn none of this — about Grenada or about anything else that might call into question the U.S. authority to impose its will wherever and whenever it wishes. The specifics of the Grenada invasion are unique, but when students are encouraged to ask critical questions, they can recognize that intervention in Grenada is part of a pattern that includes Vietnam, Iran, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Iraq, and so many others. Each instance is promoted with only slightly different justifications. When President Obama recently wanted to attack Syria, he read from the same script as his predecessors: “My fellow Americans, for nearly seven decades the United States has been the anchor of global security.” No. If students knew our history, they would know this is not true. If students knew our history, they would be more skeptical when U.S. leaders decide that they have the right to determine how people in other countries should live.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Published on Common Dreams | Huffington Post.

© 2013 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Photo credits:

- Forward ever, backward never! poster. North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA).

- Maurice Bishop welcome poster. University of the West Indies, Roland Graham Collection.

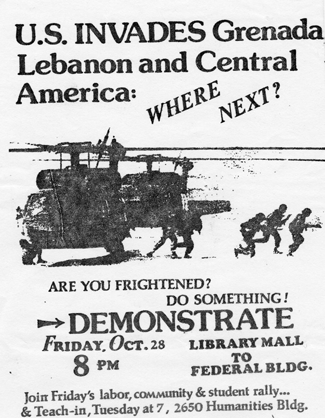

- Student protest poster for Oct. 28 demonstration. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- President and Nancy Reagan at a memorial service. WikiMedia Commons.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn