During the early 1950s, the city of Los Angeles forcefully evicted the 300 families of Chávez Ravine to make way for a low-income public housing project. The land was cleared and the homes, schools and the church were razed. But instead of building the promised housing, the city — in a move rife with political controversy — sold the land to Brooklyn Dodgers baseball owner Walter O’Malley, who built Dodger Stadium on the site. The residents of Chávez Ravine, who had been promised first pick of the apartments in the proposed housing project, were given no reimbursement for their destroyed property and forced to scramble for housing elsewhere.

During the early 1950s, the city of Los Angeles forcefully evicted the 300 families of Chávez Ravine to make way for a low-income public housing project. The land was cleared and the homes, schools and the church were razed. But instead of building the promised housing, the city — in a move rife with political controversy — sold the land to Brooklyn Dodgers baseball owner Walter O’Malley, who built Dodger Stadium on the site. The residents of Chávez Ravine, who had been promised first pick of the apartments in the proposed housing project, were given no reimbursement for their destroyed property and forced to scramble for housing elsewhere.

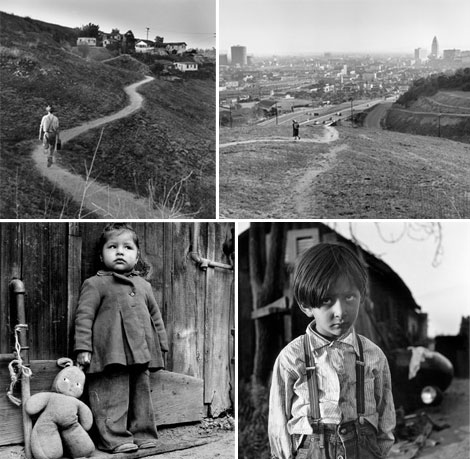

In 1949, photographer Don Normark visited Chávez Ravine, a close-knit Mexican American village on a hill overlooking downtown Los Angeles. Enchanted, he stayed for a year and took hundreds of photographs documenting community life. But little did Normark know that he was capturing the last images of a place that was about to disappear — within a few short years, the entire neighborhood would be gone. Chávez Ravine: A Los Angeles Story tells the story of how this Mexican American community was destroyed by greed, political hypocrisy and good intentions gone awry.

Photographer Don Normark in an early self-portrait.

In this film, filmmaker Jordan Mechner explores what happened, interviewing many of the former residents of Chávez Ravine as well as some of the officials who oversaw the destruction of the community. Narrated by Cheech Marin and scored by Ry Cooder and Lalo Guerrero, Chávez Ravine combines contemporary interviews with archival footage and Normark’s haunting black-and-white photographs to reclaim and celebrate a beloved community of the past. [Description from Independent Lens.]

Background

Located in a valley a few miles from downtown Los Angeles, Chávez Ravine was home to generations of Mexican Americans. Named for Julian Chavez, one of the first Los Angeles County Supervisors in the 1800s, Chávez Ravine was a self-sufficient and tight-knit community, a rare example of small town life within a large urban metropolis. For decades, its residents ran their own schools and churches and grew their own food on the land. Chavez Ravine’s three main neighborhoods — Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop — were known as a “poor man’s Shangri La.”

The death knell for Chavez Ravine began ringing in 1949, the same year that Don Normark captured his collection of photographs of the community. The Federal Housing Act of 1949 granted money to cities from the federal government to build public housing projects. Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron voted and approved a housing project containing 10,000 new units — thousands of which would be located in Chavez Ravine.

Viewed by neighborhood outsiders as a “vacant shantytown” and an “eyesore,” Chávez Ravine’s 300-plus acres were earmarked by the Los Angeles City Housing Authority as a prime location for re-development. In July 1950, all residents of Chavez Ravine received letters from the city telling them that they would have to sell their homes in order to make the land available for the proposed Elysian Park Heights. The residents were told that they would have first choice for these new homes, which included two dozen 13-story buildings and more than 160 two-story bunkers, in addition to newly rebuilt playgrounds and schools. Some residents resisted the orders to move and were soon labeled “squatters,” while others felt they had no choice and relocated. Most received insubstantial or no compensation for their homes and property.

Film Clip

Using the power of eminent domain, which permitted the government to purchase property from private individuals in order to construct projects for the public good, the city of Los Angeles bought up the land and leveled many of the existing buildings. By August 1952, Chávez Ravine was essentially a ghost town. The land titles would never be returned to the original owners, and in the following years the houses would be sold, auctioned and even set on fire, used as practice sites by the local fire department.

The plan for Los Angeles public housing soon moved to the forefront of a decade-long civic battle. The story of Chávez Ravine is intertwined with the social and political climate of the 1950s, or the “Red Scare” era. While supporters of the federal public housing plan for Chávez Ravine viewed it as an idealistic opportunity to provide improved services for poor Angelenos, opponents of the plan — including corporate business interests that wanted the land for their own use — employed the widespread anti-communist paranoia of the day to characterize such public housing projects as socialist plots. In 1952, Frank Wilkinson, the assistant director of the Los Angeles City Housing Authority and one of the main supporters behind Elysian Park Heights, faced questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was fired from his job and sentenced to one year in jail.

The Los Angeles City Council attempted to cancel the public housing contract with federal authorities, but courts ruled the contract legally binding. But by the time Norris Poulson was elected mayor in 1953, the project’s days were numbered. Poulson ran for office using the Chavez Ravine controversy as a platform, vowing to stop the housing project and other examples of “un-American” spending. After much negotiation, Poulson was able to buy the land taken from Chavez Ravine back from the federal government at a drastically reduced price, with the stipulation that the land be used for a public purpose.

Los Angeles was also a rapidly growing city in the 1950s. Despite its expanding population, the city had yet to host a major-league sports team. County supervisor Kenneth Hahn began to scout out potential teams that might be willing to relocate to Los Angeles, including the Brooklyn Dodgers. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley soon struck a deal with the city officials, acquiring the minor league Los Angeles Angels and its small ballpark with the promise of a new stadium to be built on the land from Chavez Ravine. As Frank Wilkinson explains in the film Chávez Ravine, “We’d spent millions of dollars getting ready for it, and the Dodgers picked it up for just a fraction of that. It was just a tragedy for the people, and from the city it was the most hypocritical thing that could possibly happen.”

O’Malley’s move to Chávez Ravine did not occur without major controversy. Vicious inter-city politics included allegations of Mayor Poulson making illegal deals with the Dodgers while betraying the public, while supporters of the stadium, including public figures such as Ronald Reagan, argued that opponents were “baseball haters.” In the end, O’Malley supporters won a public referendum by only three percent, allowing O’Malley to build the stadium in exchange for giving the Angels’ ballpark back to the city. Additional lawsuits froze the official transfer of land and delayed construction, but in 1959, the city began clearing the land for the stadium after removing the last few families that had refused to leave Chávez Ravine. On April 10, 1962, the 56,000-seat Dodger Stadium officially opened. [Background from Independent Lens.]

Film website on Independent Lens | Purchase from Bullfrog Films.

This is a sad story but it was also so touching. I feel for the people that lost their homes; it’s hard moving so I couldn’t imagine getting forced out of their homes. We don’t even know parts of our country’s history.

It was very heart breaking to find out that the government lied to all the citizens of the neighborhood, and instead went for the money instead of doing the right thing.

This is a very touching story. Hopefully history doesn’t repeat itself.

Wow, crazy how much we don’t know about our own country’s history. So sad that all those families had to leave their homes. It’s sad that something like this was destroyed by the greed and hypocrisy of others.

This really touched my heart. I remember this happening… and I am grateful that I found this!!! Thank you

It is a heartbreaking story how the Dodgers just kicked 300 families out of their home because of political hypocrisy and greed. The majority of the families there have been there for hundreds of years and all the memories that have been made there were just destroyed.

My father lived in Chavez Ravine, he was from La Loma. He often talked about the place he lived and how they were thrown out by force. He loved looking at the book over and over as he got older. All of my brothers all bought copies of the book as well to share with our friends and family. My father recently passed away but his stories will live on with our children and grandchildren.

We will be attending a convention in, Los Angeles, next year. Dodger’s stadium was on the list of sites to see, but not anymore, we’ll bypass. Very dissapointed. Shame on you, Los Angeles.

I lived on bunker hill at the time this took place I was 15 yrs. old.and alot of my friends were from palo verde and la loma. I use to go into their neighborhood and we would hook up to go to the orpheum movie house on 9th and broadway downtown. It was terrible watching the bulldoizers tear down my friends houses. Little did I know that just a few yrs. later bunker hill and my grandmas house would be next! We lost our house because of the clover leaf part of the freeway that came up to Temple St.

Heartbreaking.

I’m a big time Dodger fan! Since I was a kid in the 60s I never knew the real story of the people who lived in Chavez Ravine. This was so so wrong for all the families that had to leave their homes and neighborhood. Thank god for Don Normark and all his photographs he took of a one-time proud Mexican American community. The pictures show us a lot to be proud of and how our people lived in hard and good times and just dealing with everyday life. Too bad it was destroyed by greed and political hypocrisy.