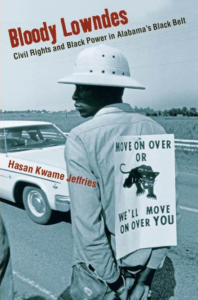

Winner of the 2010 Clinton Jackson Coley Award for the best book on local history from the Alabama Historical Association

Early in 1966, African Americans in rural Lowndes County, Alabama, aided by activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), established an all-black, independent political party called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). The group, whose ballot symbol was a snarling black panther, was formed in part to protest the barriers to black enfranchisement that had for decades kept every single African American of voting age off the county’s registration books. Even after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, most African Americans in this overwhelmingly black county remained too scared even to try to register. Their fear stemmed from the county’s long, bloody history of whites retaliating against blacks who strove to exert the freedom granted to them after the Civil War.

Early in 1966, African Americans in rural Lowndes County, Alabama, aided by activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), established an all-black, independent political party called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). The group, whose ballot symbol was a snarling black panther, was formed in part to protest the barriers to black enfranchisement that had for decades kept every single African American of voting age off the county’s registration books. Even after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, most African Americans in this overwhelmingly black county remained too scared even to try to register. Their fear stemmed from the county’s long, bloody history of whites retaliating against blacks who strove to exert the freedom granted to them after the Civil War.

Amid this environment of intimidation and disempowerment, African Americans in Lowndes County viewed the LCFO as the best vehicle for concrete change. Their radical experiment in democratic politics inspired black people throughout the country, from SNCC organizer Stokely Carmichael who used the Lowndes County program as the blueprint for Black Power, to California-based activists Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, who adopted the LCFO panther as the namesake for their new, grassroots organization: the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. This party and its adopted symbol went on to become the national organization of black militancy in the 1960s and 1970s, yet long-obscured is the crucial role that Lowndes County — historically a bastion of white supremacy — played in spurring black activists nationwide to fight for civil and human rights in new and more radical ways.

Drawing on an impressive array of sources ranging from government documents to personal interviews with Lowndes County residents and SNCC activists, Hasan Kwame Jeffries tells, for the first time, the remarkable full story of the Lowndes County freedom struggle and its contribution to the larger civil rights movement. Bridging the gaping hole in the literature between civil rights organizing and Black Power politics, Bloody Lowndes offers a new paradigm for understanding the civil rights movement. [Publisher’s description.]

Excerpts

Freedom Rights and Freedom Politics

At the moment of emancipation, [African Americans] reflected on their enslavement and identified their freedom rights, or those civil and human rights that slaveholders denied them. These rights included those enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and in various state constitutions, such as freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, and the right to due process, keep and bear arms, and vote. They also included rights that everyone is born entitled to, such as the right to own property, choose employment, enjoy economic security, marry and start a family, move without restriction, and receive and education. African Americans recognized the importance of freedom rights during slavery. Their bondage made clear that freedom rights were not only essential to living meaningful lives, but also the key to power within society. The violence of slavery, however, circumscribed their efforts to secure these rights. Only after emancipation were they able to claim them publicly. Unencumbered by the shackles of the Peculiar Institution, they insisted on a decent standard of living, pushed for social autonomy, pursued basic literacy, fought for political power, and sought protection from white violence. Even after the euphoria surrounding the jubilee subsided, their primary focus remained the guarantee of freedom rights. [From Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt, page 8.]

* * *

In the pages ahead, I tell the story of the Lowndes County freedom struggle. My purpose is fourfold. First, I aim to provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the civil rights movement. This new paradigm revolves around the concept of freedom rights — the assortment of civil and human rights that emancipated African-Americans identified as the crux of freedom. Framing the civil rights movement as a fight for freedom rights acknowledges the centrality of slavery and emancipation to conceptualizations of freedom; incorporates the long history of black protest dating back to the daybreak of freedom and extending beyond the Black Power era; recognizes African-American’s civil and human rights objectives; and captures the universality of these goals. Moreover, it allows for regional and temporal differentiation, moments of ideological radicalization, and periods of social movement formation.

Second, I strive to offer new insights into the mechanics of the civil rights movement. The struggle in Lowndes County elucidates the movement’s key organizing elements, including recruitment efforts that tapped into the Diaspora of black southerners who migrated north. It underscores the breadth of black protest, which extended for beyond voting rights. It draws attention to the special character of grassroots insurgency in the rural South. It highlights the outside forces that affected movement activism, especially white resistance and federal involvement. It helps explain the demise of movement organizing. And it complicates the movement’s standard chronology, partly by underscoring the importance of exploring black protest in the post-Voting Rights Act era. [From Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt, page 4.]

* * *

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) convention was a memorable event for the black community, which had not hosted such a gathering since Reconstruction. It was equally important to SNCC’s Alabama organizers, who had worked tirelessly to create a grassroots third party to provide an alternative to the Democratic Party. The significance of the LCFO convention, however, transcended its local meaning. The selection of seven African Americans to run against white Democrats in November 1966 was a triumph for democracy. Although there was nothing particularly radical about the candidate selection format, the process of political education that African Americans underwent leading up to the convention cut completely against the grain of American politics. After the 1965 Voting Rights Act became law, SNCC organizers developed a unique political education program for Lowndes County residents that used workshops, mass meetings, and primers to increase general knowledge of local government and democratize political behavior. As a direct result of this effort, the emerging black electorate rejected the undemocratic traditions that defined American politics. Rather than promote the interests of the socio-economic elite, draw candidates exclusively from the ranks of the propertied and the privileged, or limit decision making to a select few individuals, they adopted a freedom rights platform, selected candidates from the poor and working class, and practiced democratic decision making. In this way, the political education process gave rise to freedom politics. This new kind of political engagement coupled the movement’s egalitarian organizing methods with the people’s freedom rights agenda. The embrace of freedom politics by third-party supporters made the LCFO convention the high point of the Lowndes movement. [From Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt, page 145.]

ISBN: 9780814743317 | New York University Press

Hasan Jeffries speaking in Emilye Crosby‘s class on the Civil Rights Movement.

About the Author

Hasan Kwame Jeffries is associate professor of history at the Ohio State University, where he holds a joint appointment at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. He is the author of numerous articles including SNCC, Black Power, and Independent Political Party Organizing in Alabama, 1964-1966 — in the Winter 2006 issue of the Journal of African American History.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn