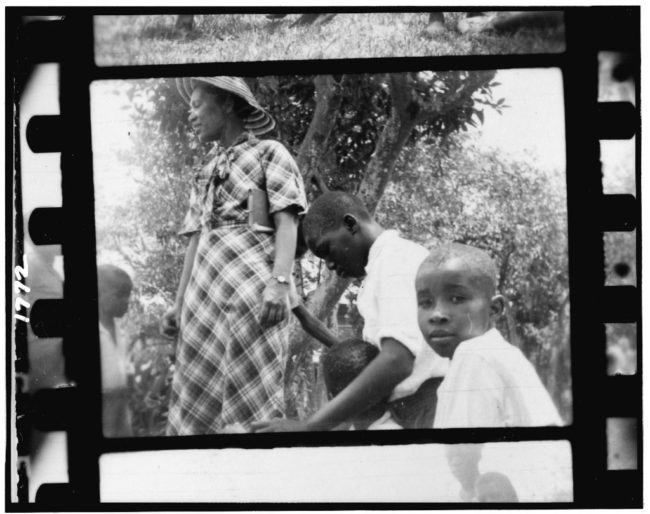

Zora Neale Hurston with three children playing a singing game in Eatonville, Florida. Source: Lomax collection at the Library of Congress.

I accept this idea of democracy. I am all for trying it out. It must be a good thing if everybody praises it like that. If our government has been willing to go to war and sacrifice billions of dollars and millions of men for the idea I think that I ought to give the thing a trial. The only thing that keeps me from pitching head long into this thing is the presence of numerous Jim Crow laws on the statute books of the nation. I am crazy about the idea of Democracy. I want to see how it feels. — Zora Neale Hurston in Crazy for This Democracy in Negro Digest (December 1945)

Zora Neale Hurston, folklorist, anthropologist, and author during the time of the Harlem Renaissance, was born in Notasulga, Alabama on January 7, 1891.

Of Hurston’s four novels and more than 50 published short stories, plays, and essays, she is best known for her 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. Author Alice Walker brought Hurston’s work to contemporary public attention.

The Florida Memory Project has a rich collection of photos, essays, and oral history interviews from Hurston’s work with Stetson Kennedy and the Works Project Administration (WPA) in Florida. Here is a short description of her documentation of labor in turpentine camps:

In 1939, Hurston went to Cross City in Dixie County, Florida, to find candidates for recording interviews, songs and life histories of interesting, everyday people. In an unusual stroke of luck, officers of the Aycock-Lindsey Company allowed her to visit their turpentine camp and collect stories, songs and other information from their laborers, who were mostly African-American. Such transparency was rare; the turpentine industry in Florida had a history marred with examples of reprehensible labor practices, unlawful debt peonage and violent discipline.

Hurston, however, was able to visit the camp, along with other representatives of the Florida Federal Writers’ Project (FWP.) Her essay, “Turpentine,” traced her travels through the pine forests with an African-American “woods rider” named John McFarlin. Her work on Florida’s turpentine camps is still considered authoritative. Continue reading.

In August of 1955, Zora Neale Hurston wrote a letter to the editor of the Orlando Sentinel condemning the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. In it she said,

The whole matter revolves around the self-respect of my people. How much satisfaction can I get from a court order for somebody to associate with me who does not wish me near them?

. . . It is a contradiction in terms to scream race pride and equality while at the same time spurning Negro teachers and self-association.

To bring Hurston’s story to the classroom, we recommend the related resources listed below including the film Zora Neale Hurston: Jump at the Sun and two chapter books for upper elementary and middle school, Zora and Me and Scraps of Time.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn