Archivists, historians, and educators gathered online for a session called “Radicalizing the Archives” during the week of activities to commemorate the Howard Zinn Centennial. The session drew on Zinn’s speech at the 1970 Society of American Archivists conference when he urged archivists “to take the trouble to compile a whole new world of documentary material, about the lives, desires, needs, of ordinary people.” The panelists highlighted efforts to humanize the archives. There were opportunities for attendees to meet in small groups so that everyone could participate.

This event was held on August 25, 2022 and hosted by the Howard Zinn Revocable Trust, Teaching for Change, and Tamiment-Wagner Collections of New York University. The presenters, listed below, offered a range of experiences in the field.

Lauren Cooper, HowardZinn.org digital curator with Teaching for Change; Center for Black Digital research librarian and managing director, Penn State University; formerly the staff coordinator for the Zinn Education Project.

Michael Koncewicz, Michael Nash Archivist & Ewen Center Program, Tamiment-Wagner Collections, New York University, author of They Said No to Nixon: Republicans Who Stood Up to the President’s Abuses of Power

LaShawn D. Harris, associate professor of History, Michigan State University; Organization of American Historians (OAH) Distinguished Lecturer, 2019-2022; and author of Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy

Linda García Merchant, public humanities data librarian, University of Houston; co-founder of Chicana por mi Raza Digital Memory Collective.

Nancy Raquel Mirabal, associate professor of American Studies, University of Maryland, author of Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad in New York, 1823-1957.

The event was designed and hosted by Lauren Cooper and Michael Koncewicz. Shannon O’Neill of Tamiment also helped with the session design.

The participants included teachers, librarians, journalists, archivists, and historians. Here are selected introductions from the chat to provide a sense of who was “in the room.”

Kenya Lane, African American history consultant with the South Carolina Department of Archives and History

David Barsamian and Joe Richey here in Boulder curating the Alternative Radio archive

Kelly Barnes, high school history teacher (U.S. and world), Baltimore City. Prepping my room!

Cynthia Wise, postdoctoral fellow in Borderlands & Ethnic Studies at New Mexico State University (Las Cruces)

Bob Lederer, Outfm.org producer, Pacifica Radio/WBAI & independent researcher, developing multi-media project “Queerly Defiant” about intersectional LGBTQ-TS+ folks facing govt. repression

Carolee Klimchock, community archivist and historian at Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation

Lois Ahrens, The Real Cost of Prisons Project, based in Northampton

Brenda Berkman, New York City. Working to archive women firefighters histories at Tamiment.

Vivian Rothstein, Los Angeles, created a labor archive at UCLA on the history of UNITE HERE Local 11, the Hotel Workers Union

and many more

Introduction

Lauren Cooper opened the session. She noted,

The jumping off point for this session is Howard Zinn’s 1970 talk at the Society for American Archivist Conference. Zinn urged archivists to “take the trouble to compile a whole new world of documentary material about the lives, desires, needs of ordinary people, and is often cited by those in the field whose work includes methods to humanize the archive with a practice of anti-racist and anti-colonialist methods.” While Zinn wasn’t alone in that charge, he pierced through conventional professional standards inspiring archivists, still today.

Since 2020, when the world witnessed the murder of George Floyd by police and the subsequent uprisings, there’s been a surge of activities by institutions to highlight obscured histories and seek ways to improve public and private archives.

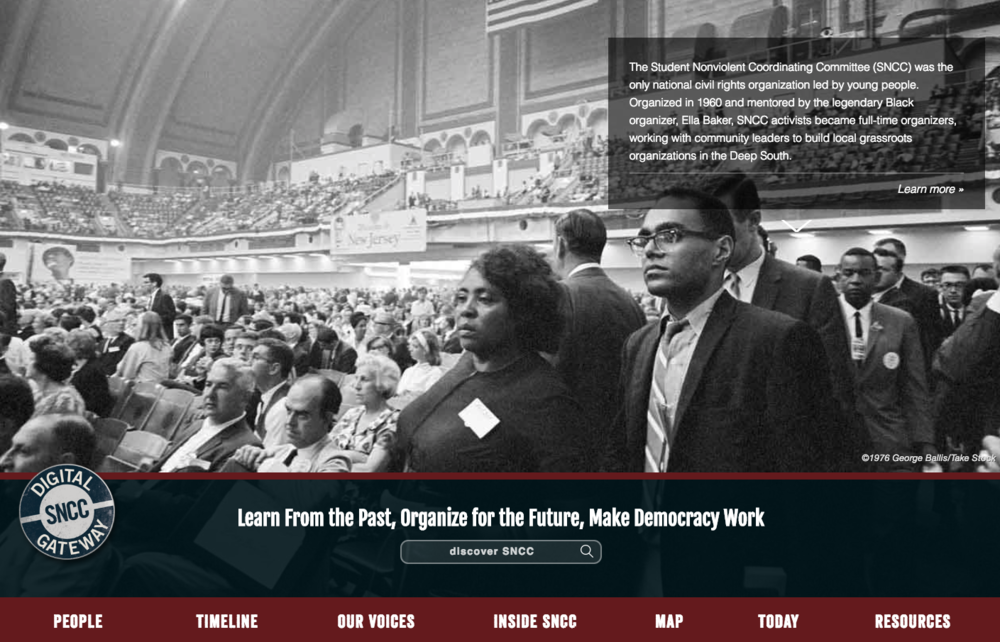

This session will focus on highlighting the work of humanizing the archives, and ask what opportunities and challenges lie ahead, and also look at what communities and groups have already been doing on their own for years. Organizations like the South Asian American Digital Archive, Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project, and the Interference Archive.

The conversation we have planned most often happens at professional conferences or in closed circles. This requires either membership or registration fees, or an insider status. The sharing and dissemination of practices, lessons learned, challenges, and accomplishments tend to stay in those corridors.

So we’re here as archivists, curators, librarians, historians, researchers, teachers, activists, community members, and the curious to learn from each other about our challenges and opportunities and, hopefully, collect ways to move forward.

Recording

The event recording includes the presentations (10 minutes each) and the Q&A session. (The small group discussions were not recorded.)

Full Transcript

Note that this transcript was auto-generated with light corrections. It is offered as a resource but not to be quoted since there may be errors.

Lauren Cooper: Hello! If you’re just joining us, welcome! We have a full plate today of presenters, but also discussion and sharing with each other. So, I’m going to go ahead and get us kicked off with an introduction. First, thank you all for joining us, thanks to the Howard Zinn Digital Trust and the Tamiment Library for their support for this event. Just to note we are recording this for internal use. We’re going to use the recording to edit the presentation clips, but we won’t be broadcasting any conversations. We want to nurture a room of safety and openness. If you have any questions about that, you can email us at HowardZinn.org.

So, the jumping off point for this session is Howard Zinn’s 1970 talk at a Society for American Archivist Conference, called the Activist Archivist, and subsequently published in 1977 as Secrets, Archives, and the Public Interest. Zinn urged archivists to “take the trouble to compile a whole new world of documentary material about the lives, desires, needs of ordinary people,” and is often cited by those in the field whose work includes methods to humanize the archive with a praxis of anti-racist and anti-colonialist methods.

While Zinn wasn’t alone in that charge, he pierced through conventional professional standards inspiring archivists still today. Since 2020, when the world witnessed the murder of George Floyd by police and the subsequent uprisings, there’s been a surge of activities by institutions to highlight obscured histories and seek ways to improve public and private archives.

This session will focus on highlighting the work of humanizing the archives, and ask what opportunities and challenges lie ahead, but also look at what communities and groups have already been doing on their own for years: Organizations like the Southern Asian American Digital Archive, Densho (the Japanese-American legacy project), and the Interference Archive, which explores the relation between cultural productions and social movements. The conversation we have planned seems to mostly happen at professional conferences or in closed circles. This requires either membership or registration fees, or an insider status. The sharing and dissemination of practices, lessons learned, challenges, and accomplishments tend to stay in those corridors.

So we’re here as archivists, curators, librarians, historians, researchers, teachers, activists, community members, and the curious to learn from each other about our challenges and opportunities, and hopefully collect ways to move forward.

I’m going to go through the goals of the presentation. So the goals are an open conversation between archivists, curators, librarians, historians, and researchers, community members and teachers about the process and methods, challenges and opportunities of the work we do and identify ways we can build on the work that has already been done in ways to enhance that, to bring obscured histories to light with care and intention.

The outcomes are hopefully trying to look at how or where we can synchronize ways that inform each other’s work. What are the challenges and opportunities of how to bring this to light? We’ve asked the speakers to talk about several topics that they could choose from: Either discussing their own projects, the challenges they faced, and how they manage through them; how humanizing the archive is transforming scholarship and the need to process hidden collections within the archives that have been ignored; how institutions can go beyond the pledge to do better to ensure they shift priorities to continue transforming who their collections reflect and support and recruiting the staff to conduct the work. So, the outline for this event today: We’re going to hear from archivists and librarians for about seven minutes each. We’re then going to go do a little collective writing and responding to issues raised. There’s also questions that will be raised on a shared Google doc.

We’ll go into breakout rooms where people can talk to each other and share aloud things that are on their mind. We’ll then come back and hear from the historians, again do another collective writing session and breakouts, and then we’ll reconvene as a group and pull together some of the major threads of conversation that were happening in the breakout rooms. After the event we’ll attempt to synthesize the discussion points, and share out to everyone who’s registered. And with that I will turn it over to Mike.

Michael Koncewicz: Thank you, Lauren, for all the work you’ve done in putting this event together. Thank you to Deborah and everyone at the Zinn Education Project. This is a special event. I think it’s worth mentioning very quickly that this forum is a unique opportunity for archivists, historians, librarians, educators, curators, and anyone who’s interested in history to discuss how we engage with the archives. Our interactions in reading rooms and on Zoom and via email are too often focused on meeting our own deadlines, and as a result, we don’t have enough time to examine the meaning of our work and identify where we overlap and diverge from one another, and in a productive manner.

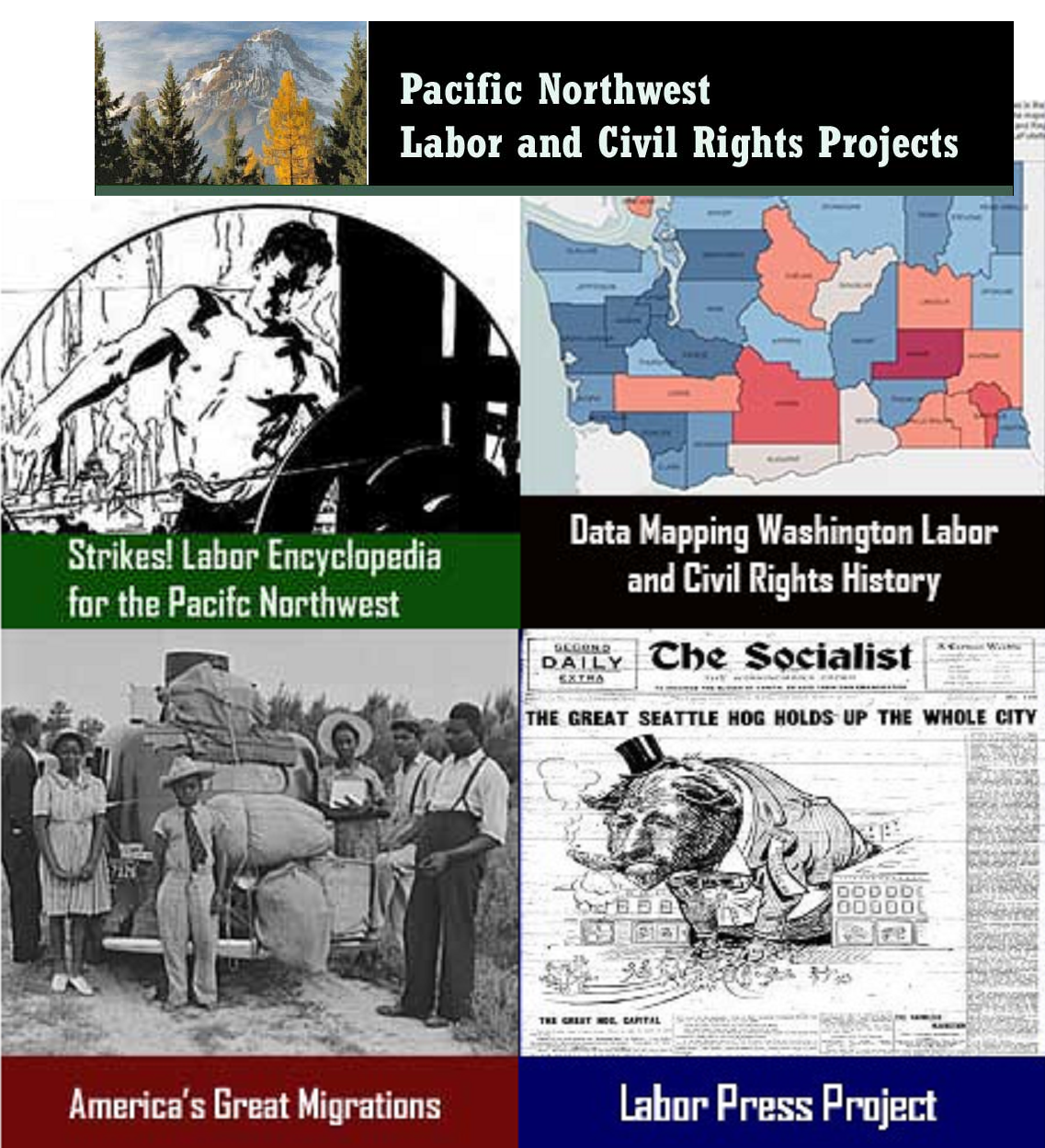

I want to thank you all for being here, and I hope this event will inspire other similar conversations that focus on the best ways to document the history of working people. It’s my pleasure to introduce our first set of presenters, who are emblematic of those discussions. First is Linda Garcia Merchant. She is the Public Humanities Data Librarian at the University of Houston, co-founder of Chicano Por Mi Raza Digital Memory Collective, and the presentation “Disrupting the Absent Presence.”

Linda García Merchant (she|her|ella): Thank you, Michael, and thank you to the Zinn Centennial Committee. I’m going to go ahead and share my screen. Can everyone see my screen? Okay, good. The title of this presentation asks us to consider what it means to disrupt our understanding of the history of the Chicano and women’s movements of the 1960s and 1970s, by introducing an archive of photographs, documents, and ephemera that brings marginalized voices to the center of a conversation with a community of scholars, practitioners, activists, and students. With the Archive at the center of that conversation as a place that Maria Gutierrez describes as the archive of encuentro, or encounter, that is about the cultivation of relationships to teach and mentor to build a sustainable archive.

I offer the photos in this title slide as an example why this kind of conversation is important to the sustainability of archives that foreground culture and gender. The first photo is members of the Chicano Welfare Rights Organization, and includes Jesse Corona, Pat Esada, Anita Gomez, one of the foremothers of Chicano feminism, and Alicia Escalante, a pioneer in the welfare rights movement.

The second photo includes the members of the Census Advisory Committee on the Spanish origin population for the 1980 census. This committee, formed in 1975, lasted for five years and included two members of the Chicano Caucus of the National Women’s Political Caucus, Gracia Molina de Pick from San Diego and Rhea Mojica Hammer from Chicago. The next photo is a group of University of Wisconsin-Madison students preparing to interview Leonor Rosas, a Latina with family involved in La Raza Party and the Brown Berets from Milwaukee, Wisconsin for the Somos Latinas Digital History Project. The last photo is of two students prepping documents for scanning during the entity of the Vasquez Digital Public History Project Field School in Northern New Mexico.

Now, without the context of my narrative, these photos might exist in an archival collection removed from their connections to location, movement, action, influence, and other related documents. Each of these photographs represents milestones in the history of the Chicano Por Me Raza Digital Memory Collective, or CPMR, both in documenting our existence as a collective, and in the importance of documenting our existence and contributions to Chicana-Latina history in the United States.

This example of images cultivated, preserved, and published as active participants in the conversation of the archive creates opportunity for ongoing dialogue with the materials and subjects as historically and geographically situated. The Chicana Por Me Raza Digital Memory Collective is a group of historians, educators, students, researchers, archivists, and technologists dedicated to preserving imperiled Chicanx and Latinx histories of the long Civil Rights Era. Our project begins in 2009 at the University of Michigan, where Dr. [Maria] Cotera was an associate professor. In 2013, we are joined by our digital archivist, Marco Seiferle-Valencia, who, as he describes our collection process at that point: “Puts order to chaos.”

Maria [Cotera] and I started this project because we knew that the archival absence of Latina contributions of the civil rights era in no way reflected the historical reality because our mothers, Rhea Mojica Hammer (my mother) and Martha Cotera (Maria’s mother) had both been instrumentally involved in Latinx politics and the women’s movement along with Alicia Escalante, Anita Gomez, and Gracia Molina de Pick, who held encyclopedias of knowledge about this era.

We wanted to preserve the Chicano archives so that its knowledge was not lost. But how could we, as scholars, recover this archive and maintain its radical nature outside of the institution? The Chicano Por Mi Raza Repository is housed at the Texas Advanced Computing Center, or TACC, using a collection software called Clouder, a customizable and scalable data management system. Our login-based system supports a virtual production community to collect, upload, and curate assets from anywhere in the world, working with project partners in any institution on assets protected by institutional security. Scholars, practitioners, and independent researchers work with subjects and their communities of knowledge holders to reconstruct the content and context of each asset.

Our collective is a virtual community sustained by trust in the democratized methods and motivations of the original architects of this model: the women of the archive. CPMR exist because of the infrastructures like CAT and technologies like Clouder implemented and securely maintained. This model begs the question: Without this type of institutional commitment to this kind of autonomous production, how can we assure the stability and sustainability of this work? CPMR reflects a significant history absent of infrastructure, a collective and archive operating in a continued space of precarity, relying upon a series of serendipitous moments and Vasqueza strategies to persevere in existing. Such was the case for the first eleven years of this project.

It is only in 2020 when Dr. Cotera accepts a position at the University of Texas-Austin, that CPMR gets a more permanent home on our terms. Building this community means building networks of participants that includes both subjects and practitioners in a multidisciplinary approach to the accumulation and discourse of knowledge. These are not just networks of the content or community being collected. They include the technological needs of collections, archivists, writers, media specialists, practitioners, and infrastructure technologists that help to create and support the community. It is an approach that expects that all knowledge is equal, all knowledge has value, and all contributions are both sound and important to a collaborative production. Collaboration means understanding the importance of an ongoing, often permanent relationship with the community to the archive. Here the scholar and institution can provide the ongoing pedagogical role of mentoring and teaching to and about the archive in the classroom, the community center, and the living room.

I ask us to re-imagine how this method of encuentro that disrupts knowledge production translates to our scholarship and mentorship and produces visibility for these archives at the margins within our institutions by merging access and adaptability of technological research infrastructures. What does it mean for our future to teach from these deliverables we’ve helped to build that allow students, community, and faculty to be in conversation with these archives in the classroom, in the community center, and the living room? It means that in this way we are building intragenerational collectives, not collections.

Koncewicz: Thank you, Linda. Next is Lauren Cooper, HowardZinn.org digital curator with Teaching for Change and the Center for Black Digital Research librarian and managing director at Penn State University. Her presentation is on humanizing digital scholarship, methods, and practice.

Cooper: Great, and thank you, Michael. I’m Lauren, my pronouns are she/her, and I am a Muskogee Indian of the Creek Nation, currently of Oklahoma, formerly of Georgia, and Akimel O’Odham of the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona. Before becoming a librarian four years ago, I spent twenty years in publishing, both print and digital, working at social justice organizations whose missions were to amplify the voices and histories that are hidden, missing, marginalized, and silenced. I bring this experience to my work as a librarian, and in how I try to center the humanity in digital work.

This is a lightning talk of a much longer talk, but it’s a talk of putting principles into practice. Also, as a Native American woman with a senior leadership role in a Black History Center, I also share about something that can be uncomfortable for many of us — having professional humility when working on projects representing people and communities that are not your own.

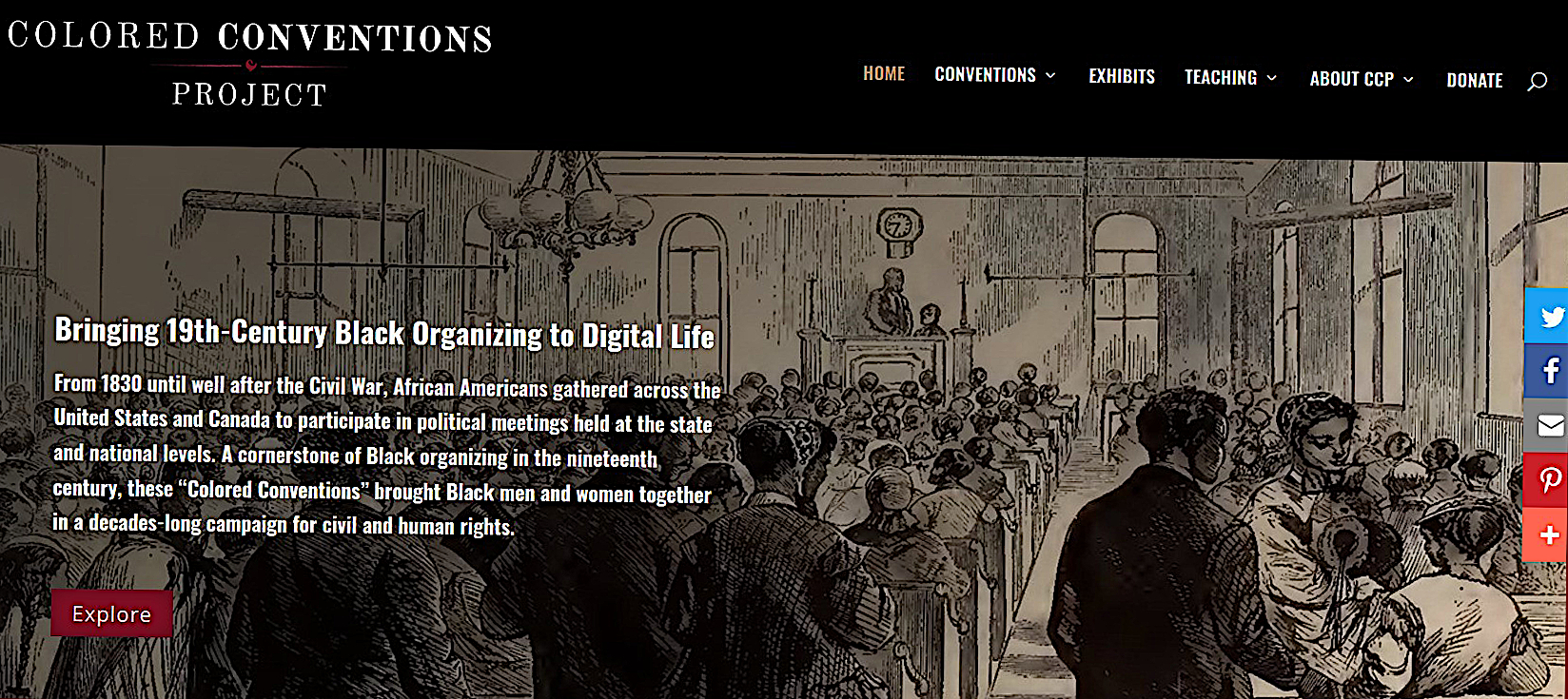

So, some background. I’m the digital scholarship librarian and managing director for the Center for Black Digital Research. This is our team from our group meeting earlier this week. We’re about thirty people, including the people on the Zoom screen in the background. We’re a collaboration of faculty, grad students, undergraduates, librarians, and community members. The Center houses the Colored Conventions Project, Douglass Day, and the Black Women’s Organizing Archive, and you can find out more at digblk.psu.edu.

I’m going to talk about my work with the Colored Conventions Project, or CCP, which is the longest running of the three, and focuses on bringing the buried history of the Colored Conventions Movement to digital life. This movement, started in 1830, spanned seven decades. It convened hundreds of state and national Colored Conventions across the U.S. and in Canada to bring Black people together in order to organize and strategize for racial justice.

CCP is guided by a set of principles. I’m going to speak specifically to principal two: We pledge to account for Black women’s labor and leadership in our own historical work and in our own project practices. Principle three: Our project aims to highlight and center Black lives. And principle five: We seek to name Black people in communities as an affirmation of the Black humanity inherent in Black data curation.

Here are some examples of putting these principles into action. The first is concerning visual representation, ensuring digital space for Black women. In 2018, a new crew of us were responsible for completing a website migration that had been in progress for two years. Featured here are all of the people that worked during that time period, 2018 to 2020.

As we prepared for launch, we noticed several design issues that did not abide by our principles. The first concern was visual representation and avoiding stereotypes. Working on the overview page for our digital exhibits, it gave me pause that for our exhibit on the Colored Conventions and the carceral state we were using an image of a child chain gain.

This image was troubling because it could reinforce the stereotype of Black males in prison, especially the stereotype of young Black males in prison. And if someone was scanning this page, this is the visual impression they would be left with. Not only that, but we were missing an opportunity to highlight the exhibit’s actual narrative, which was the Colored Conventions protest against the justice systems of California and Georgia, and the Black women reformers in the 1800s who contributed to that resistance against incarceration.

I raised these points to Kelli and Michelle, and we chose to feature instead portraits of Selena Sloane Butler, an education activist who is well known for her critiques and condemnation of Georgia’s incarceration system, and Ethel Wilson, a woman of financial means that was demonized by the media and ultimately convicted of a crime even though there was no physical evidence. We then examined all the other featured images and chose ones that you might not often see of Black life in the 1800s — dignified portraits of Black leaders, Black business owners, and Black women in a classroom, to name a few.

The next is ensuring digital space for Black women. In our digital exhibits that were rich with personal biographies, namely women’s biographies, they were bundled together on a single page in an effort to keep the menu structure simple. However, this caused lots of scrolling through a long page to get through and to see everyone represented, and the pages were hard to cite or make a direct link to. Kelli, Michelle, and I discussed this and decided to create separate pages for each of the women’s biographies, so their names would be visible on the menu navigation. This set us back a couple of weeks, but we felt it was critically important. Here are some examples where we made one page into several pages.

In our end of semester report, as we accounted for our time delay, Kelli eloquently wrote that we took the extra time because consolidated pages were “causing women’s names, lives, and contributions to be in a ‘bulk bin’ of information: their name isn’t seen in the Exhibit menu, and you have to dig through a page. [The layout] doesn’t provide their lives the digital space their male counterparts may receive, or give their lived lives the oxygen and space(s) they may have struggled for.”

And then my third and final example is about listening to the core community and having humility and the work we do. The three of us wrote a blog series to document the behind the scenes work. It was written in chronological order in the order that we proceeded through the work and was to be rolled out as follows: project management, platform decisions and implementation, quality assurance, URLs and scholarly implications (parts one and two), and ensuring digital space for Black women and access to Black histories.

Two African-American senior faculty members, Doctors Gabrielle Foreman and Kim Gallon, told us no way should Black women be last on the list. My immediate response was, “They’re not last. We have more coming. That’s where it just happened to end at this moment. The narrative structure won’t fit if we move it around.” They followed up with, “Nope, you need to rearrange it. As a Black female academic, if I saw that on someone’s page it would signal to me where their priorities are and how they prioritize Black women.”

They were right. Despite all my experience, I missed this, and I was being defensive instead of hearing them. In self-reflecting, I asked myself why I was so wedded to adhering to the timeline, to traditional publishing standards, and this is one of the challenges of our field: The issue of professional protocols or practices deemed superior over the voices and priorities of the community being represented. Our educational, professional, and technical expertise is only one part of the work. I advocate that we use our skills to find ways that things can be done differently in different ways, to not be gatekeepers, but to be collaborators. So the blog posts, it would take some time to edit and rearrange them so they transition smoothly, but the impact, the visual significance, and more than that, the mutual respect will be long-lasting. Thank you.

Cooper: Next, we are going to head into the historian section of the presentation. The first person we’re going to hear from is LaShawn D. Harris, Associate Professor of History at Michigan State University. Dr. Harris is an Organization of American Historians book prize winner, a distinguished lecturer, and author of Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy, by the University of Illinois Press. I will turn it over to you.

LaShawn Harris: Thank you, Lauren, Michael, Shannon, and my fellow panelists for organizing and participating on this panel on such an important subject. I hope that archivists and historians will continue to have conversations about our respective work, and talk about the different ways to address issues in the archive as well as ways to collaborate.

My research interests include urban, working-class Black women’s history, their labor lives, interior lives as wives, lovers and pleasure seekers, their grief and loss, their dreams and thoughts about economic stability and racial uplift and respectability, and the different ways they navigated and contested various forms of race, gender, and class exclusion, as well as intra-racial tensions. In the vein of scholar, historian, and activist Howard Zinn, my research and approach to writing history is, “I’m going to write about what I think is important. The social struggles of people, the class structure in the United States, the racial problem, and the problem of sexuality and inequality in the country.” Like Zinn, those are things and subjects that guide my research.

I plan on talking a little bit about my research experience writing my first book, which is entitled Sex Workers, Psychics and Number Runners Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy. Also, some of this is relevant to the current thing that I’m doing now, which is on Black women’s activism and experiences with the police during the 1980s in New York City. Exploring the lives, labor, aspirations, and worlds created by urban working-class Black women was, and continues for me to be an exciting, challenging, and frustrating endeavor. Concerns and even fears about the dearth of primary documentation on women profiled in my work made at times the thought of archival researching really daunting.

As I began recovering and piecing together surviving documents on urban women, I encountered several archival issues. The scarcity and even unavailability of primary material, complicated initiatives to excavate women’s family backgrounds, labor patterns, and physical journeys throughout one of the nation’s most fascinating cities, New York. Textual absences and voids illuminated the many limits of the archive, which historian Marisa Fuentes and other scholars of Black women’s experiences described as a fraught space for marginalized bodies.

In her seminal essay, which came out in 1987 in the Journal of American History, the essay by Deborah Gray White, which is entitled Mining the Forgotten: Manuscript Sources for Black Women’s History, White rightfully points out that part of the difficulties in excavating Black women’s lives and bringing their stories to the center of historical inquiry is the archive itself. White comments that Black women’s worlds have been peripheral to those most likely to keep records of any kind, thus making Black women’s voices and stories scarce within manuscript collections. Considered unworthy of scholarly exploration, and excluded from historical archives, women of color, especially those that lack privilege and power, have remained on the fringes of history.

In their edited volume, which is entitled Contesting Archives, Finding Women in the Sources, scholars including Sherry Katz, Mary Elizabeth Perry, Kali Gross, and others, attribute Black women’s missing loss or destroyed primary documentation to “the lack of archival objectivity and disinterested institutions that house historical documents and artifacts.” Historian Ashley Farmer, in a 2018 Modern American History Journal article, also rightfully asserts,

Recent histories are raising methodological questions and concerns. How should historians conceptualize the archive? What can be discerned from traditional and non-traditional sources? How do scholars interpret and account for the power dynamic that the archive reproduces? And how should this dynamic inform historical inquiry and methodology?

Upon locating rare archival documentation on working-class Black women’s personal and private worlds, which included contradictory, fragmented, and missing biographical sketches and labor accounts, I was reminded of the difficulties of tracing, understanding, and analyzing early twentieth century Black women’s nonlinear footsteps. At the same time, and as one scholar rightfully noted, exploring such “contradictions, silences, and collisions” in the documents presents an opportunity for scholars to number one, read and interpret historical figure silences and pose new questions about those subjects, two, to engage in various forms of informed historical speculation, and three, import an interdisciplinary lens or approach.

For me that means using the work of twentieth century poets, novelists, musicians, and other writers, such as Claude McKay, Roi Ottley, Ann Petry, Toni Morrison, and even soul singers, Marvin Gaye and Rick Jones. Number four, having ongoing conversations with my partners in the struggle and documenting lesser known histories, and that includes archivists and historians about such challenges. Some of these informal conversations over coffee and lunch included advice on other collections that will be useful to my work, as well as archivists disclosing the limitations of their institutions, the challenges and politics of archival collecting, especially in a moment of COVID, and how historians and archivists should continue to engage in such dialogue, and also connecting me with other scholars who are doing similar work. And five, as Ashley Farmer reminds us and recommends, that historians and archivists should make a commitment to doing more with less. If we can commit to doing more with less, we can produce histories that reveal the narratives and the voices of a diverse group of understudied communities and workers and activists whose lives were complex and characterized by victimization and agency, and the constant struggle to live out their freedom dreams. Thank you.

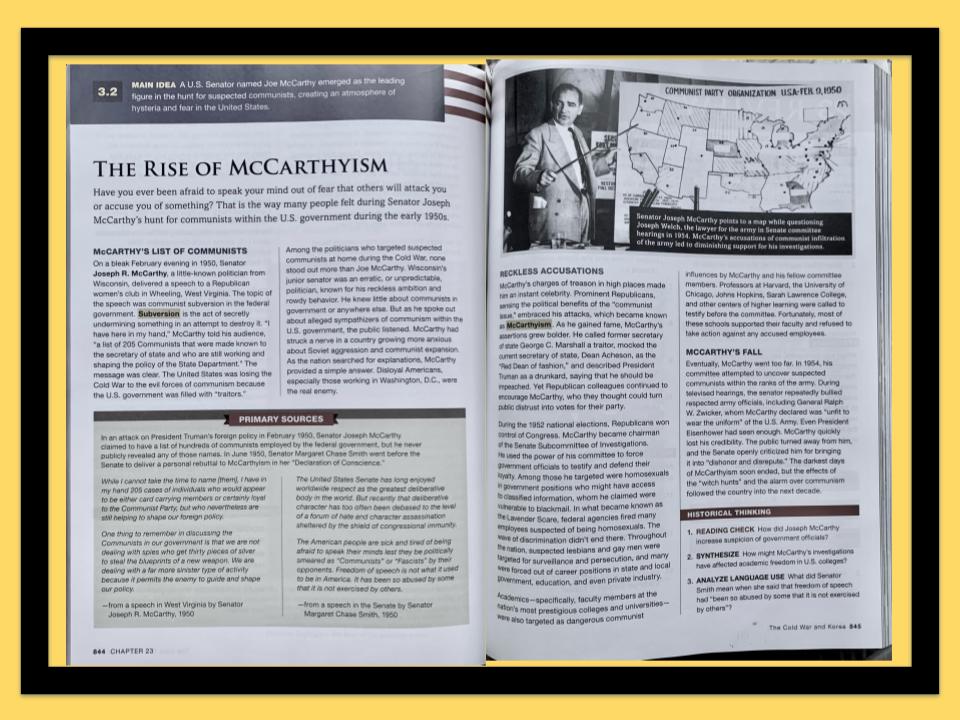

Cooper: Great, thank you for that presentation. Next is Michael Koncewicz. Michael is the Nash archivist and program coordinator at Tamiment Library and Wagner Collections, New York University, and is also the author of They Said ‘No’ to Nixon: Republicans Who Stood Up to the President’s Abuses of Power by the University of California Press. Over to you.

Koncewicz: Thank you Lauren, and once again thank you all for being here today. As a historian who has worked as a curator at the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, a renowned archive that has documented the history of labor on the left for a hundred and twenty years, I’ve had quite a bit of time to think about a lot of these issues. But our collections are truly so special, from the letters of garment workers from the early twentieth century to the posters held by Occupy Wall Street activists in Zuccotti Park in 2011, our archives span a wide range of progressive and radical social movements that have fought for a better world. That, of course, includes the Howard Zinn papers, a collection that officially opened to researchers during my very first year at Tamiment in 2014.

Our archives’ origins go back to the Rand School of Social Science, a political education center that was started by the members of the Socialist Party of America in 1906. Based in New York City, the Rands accumulated a sizable archive that covered early twentieth century New York City labor activism and certain socialist organizations. NYU acquired what eventually came to be known as the Tamiment Library in 1963, and added on the Robert F. Wagner Labor Archive project in the 1970s, a more concerted effort to document the history of New York’s Trade Union movement with help from the New York City Central Labor Council.

My colleagues and I are fortunate to be surrounded by these materials and the stories of working people that they capture. Tamiment’s collecting has helped to preserve the stories of countless radical activists, movements, and organizations. Working within the archive, I’m also reminded of the importance of repositories and institutional history in making sure that all of our community is aware of that history. That goes for using archives in the classroom, our collecting policies, and our curatorial decisions, namely, what we pick to process and showcase in our exhibitions. Despite the impressive work that my predecessors and my colleagues have done over the last few decades to diversify our collections, our archive is still heavily white and disproportionately male. That is also a part of Tamiment’s story, as is the case with many other similar archives and political institutions.

Recently, my colleagues and I have incorporated that part of our institutional history into our classes, not only because it’s the right thing to do, but because it improves their research experience. It helps explain why certain search terms don’t yield as many significant results in our finding aids. This often comes up when students ask about what we have related to Black radicalism from the 1960s and 1970s. We have materials that are useful for their research, but also encourage them to think about our archives’ history when wondering why we only have printed ephemera, why we only have a few flyers and newspapers for organizations that they are interested in. Recently Tamiment’s head curator Shannon O’Neill, who is very sad to miss out on this event, she and I have done extensive work over the last few years to sort through our massive backlog of unprocessed collections, plotting out the next several years of processing with our colleagues at NYU libraries’ archival collections management.

Keeping the library’s ongoing IDBEA initiatives at the forefront of our decision making we are prioritizing dozens of partially or wholly unprocessed collections that will be made available to all of our researchers in the coming years. These include on-process collections that have been sitting in storage for years, or collections that have had A/V items that were not included in initial processing, that were not deemed to be as important as other A/V collections that were processed. Some require additional descriptive work or rehousing in order to give researchers more information in order to preserve these valuable materials. So, that has been a key part of our work over the last few years. Collecting is a key part of our jobs. It’s the one that most people associate with our jobs. While we’ve been limited by the ongoing pandemic, we’ve initiated a COVID-19 web archiving project that captures the recent history of numerous New York City-based mutual aid labor and other related organizations.

I saw earlier in the chat Nicole Greenhouse, the library’s web archivist, who I want to shout out — Thank you, Nicole, for all of your work in helping us with this project! We were happy to receive permission from Christian Smalls in the spring of 2020, when we asked to archive his social media. But there are dozens of other examples that you can see in the link that should be dropped through the chat. We have also resumed our more traditional collecting over the last several months after pressing pause in 2020 and 2021, again paying attention to gaps within our holdings when making a decision on materials, planning an oral history project or mapping out a future exhibit.

The conversations that we’ve had with our community of donors is one of the best parts of my position. As a historian who mostly worked with government documents in my early research, my first instinct is to prioritize openness, collecting, and access. As a curator it has become clear to me that radicalizing an archive often lies in the hidden work that happens behind the scenes. I just mentioned one example: how we have worked through our backlog to try to prioritize more diverse collections within our holdings.

Aside from the work with our backlog, my colleagues, including Shannon O’Neill, have participated in reparative description work with our finding aids, identifying outdated and or harmful terms in our descriptions. Other archives are doing similar work, particularly over the last two years, as part of a broader effort to diversify their repositories. It’s a small step, but we feel it’s a significant one that should lead to better access, to a more comprehensive history of the left. Given the events of the last few years, we feel that it’s a concrete step towards diversifying Tamiment’s collections. Thank you.

Cooper: All right, thank you, Michael. Up next we have Nancy Raquel Mirabal. She is an associate professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland. Dr. Mirabal is the author of Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad in New York, 1823-1957 by New York University Press and co-editor of Keywords for Latina/o Studies by New York University Press. Over to you.

Nancy Raquel Mirabal: Okay, thank you everyone for inviting me to be here. First of all, thank you to Lauren Cooper and to Deborah Menkart for inviting me. I am so excited to be in dialogue with my colleagues. Actually it is so rare that historians can have a conversation with archivists. And so this is a wonderful opportunity to have that conversation. I have to say that there is so much that I want to say, because we rarely have these conversations. And so what I decided to do is really talk about why I do the work that I do, what I have learned along the way, and how we can make changes in the future. And I have to say that as I was listening to everyone, I think what really marks my work is that I do a certain kind of history, what Michel-Rolph Trouillot called an “unthinkable history.” It is a history that never really existed. I didn’t have sources or archives to look up when I was writing about Africa-Cuban migrants in nineteenth century New York. They simply weren’t there.

So, through my research I became fascinated with writing and thinking about, and oftentimes even creating, archives of African / Latinx diasporic communities in New York. But I’ve also done research in Florida and other places in the United States, and I think for me the key book that I continue to look to is Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past, because, as a Haitian anthropologist who really looks at the history of not only the Haitian Revolution but also the Alamo, he tells us early on to be careful of the sources and to understand that silences in the archives are often deliberate; that those silences are not just haphazard. That narratives, especially traditional narratives, mean something and have a function within a society, oftentimes in support of the nation state. That is also lessons that Hayden White and [Michel] Foucault, and so forth, always told us as well.

So with that in mind, I felt that a lot of my work is one that at the same time that I’m using sources, I’m often critical of those sources. I’m also thinking about these sources that in many ways are precarious, and to use my colleague Dr. Harris’s term “fraught” is that we have to wonder why these histories and archives are there in the first place. As I was doing my research, I always tell folks that I actually started doing my work through oral histories. Because of the narrative that we have, for instance of Cubans in the United States, is a very fixed narrative. It is one of 1959. It is one a privileged exile, and it is of a privileged white exile. That was a story that did not fit my experience. It did not fit the experience of my family. So oftentimes I tell scholars who are working, “Your story and the story of your community matters.” It can also be a part of how you do research. That was the beginning of why I did the work that I did, because I knew from my experiences, from the communities, I knew that our histories were there, and they were not necessarily being discussed, or part of the archive, or didn’t exist.

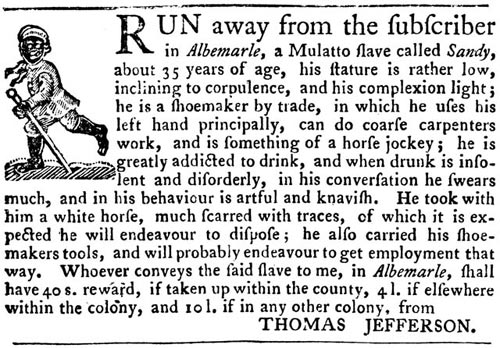

And so, as I began to do this research, I have to thank the incredible archivists, Diana Lachatanere at the Schomburg and Miriam Jiménez Román, who were my incredible mentors, who helped me to conceive of what this project could possibly look like. They gave me the name of an Afro-Cuban activist and organizer who came to New York in the 1930s, and it was through her and her experiences that I could tell this history that has not ever been told or written about. And what I learned is that I had to be almost just willing to use anything at my disposal, whether it’s newspapers, photographs, stories. I looked at musicians, the Afro-Cuban musicians, who were excluded from performing in places like the Palladium and would instead perform in the Afro-Cuban clubs that I write about. Poets, writers, anything at my disposal, I looked at.

I was incredibly promiscuous when it came to sources and archives, because you never know where you’re going to find sources. I’ll give you an example: When I was doing my research I was looking at the New York Times. That’s where you first start, the New York Times. And I remember there was a small little write-up of something called the Cuban Anti-Slavery Society. It was an anti-slavery society that was set up in 1872 by African American men in New York. It was four sentences, and it was those four sentences that took me onto a journey through and through, whether it was the Library of Congress, the National Archives. And what I was able to find through these four sentences was an incredible story of African American men in 1872, looking to include this idea of Pan-Africanism and so forth through the Cuban Anti-Slavery Society. And that was a moment of organizing.

Then, as I began to do more research, I also became, I would say, curious and fascinated by the gaps in the silences. Oftentimes the history of Cubans in the nineteenth century ends in 1901 with the end of the Spanish–American War and the U.S. occupation of the island. But these people didn’t just stop. They didn’t stop living. So what happened after 1901? What we realized is that there’s a massive migration of Afro-diasporic students coming to New York in the twenties and thirties and forties, which is why you see a rise of so many Afro-Cubans in music, sports, and so forth. And that got me thinking, “Why don’t we write about their lives as labor organizers, as people who worked, who lived, who were married, and so forth.”

It was only as performance, and how we look at the Black body as performance. That got me thinking that there was a different history to tell. And I tell you these stories because there’s a way that I love the title of this panel, which is Radicalizing the Archive, with radicalizing as a verb, as something that we can look at and change and challenge and pull apart and bring in, because that’s how we tell these histories that I also think were not meant to be told. The reason that I say that is that when I began to do work that was pre-1959 that centered Afro-Cubans that really looked at the history of Black Afro-Cuban woman as the authority, as the narrator, that challenges a completely different narration of histories that we were told were ours and were never ours to begin with.

So I think that I’ll end there. But what I’d like to add is as my colleague, Dr. Harris said, I will give you some of the ways that I also work with sources. For me the most important thing with sources is to have an initial idea of what you’re looking for. Oftentimes activists will say, “What are you looking for? We don’t know. It’s all messy. We’re trying to figure things out.” But it’s important to be curious, to really know what you’re looking at, and to not be afraid of speculation. I think Dr. Harris is actually right with that. Think of what you could possibly find, what could possibly be out there, and try to make those connections.

Also understand to navigate the silences. Just because something is not in the archive doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. It doesn’t mean that it’s not valuable. Look at something else that will allow you to then go somewhere else, and that somewhere else will take you somewhere else. My research took close to twenty years to write this book, and there was a reason for that. It meant that I needed to look at sources that were in different languages, that came from different countries. I looked at different archives, which are not always in the major archives, but in the smaller archives, and I was willing to do that.

Also, the introductory analysis is key. Look at poems. Look at stories. There was one book that I thought was really incredible. It was a book in the Schomburg, and it’s called Figuras y Figuritas by Teófilo Domínguez, who was an Afro-Cuban activist who lived in New York. He published a book in 1899, right after the Spanish–American War, of different stories of Afro-Cuban men. He included their photographs, and what he was doing was that he was building archives. He was creating what I call a future historical archive. He understood that his experience and his experience of his community would eventually be erased. They understood white supremacy. They understood how it worked, and so he created sources. It was his attempt to say we existed and here we are. So with that I think I have my time, and I just want to thank everybody.

Cooper: All right. Thank you to all our panelists in this session. A lot to think about and reflect on and hopefully map out ways that we might move forward with these challenges. I wanted to kick it off with asking the historians a question of what is something that surprised you, or you didn’t realize you had to account for and navigate around?

I’m going to kick it off by saying I was just at Tamiment this summer, and both Shannon and Mike worked with me, and were very generous with their time and very patient. I was able to get eight boxes a day out. And so I was calculating four days, that’s thirty two boxes, and I was trying to make a plan. My project is to prototype a DIY process for creating item-level catalogs of archival materials. So with forty-eight boxes, let’s see what we can do. Even with a full-time research assistant with me doing this item-level cataloging, I think we got through three or three and a half boxes of materials. So, our eyes were bigger than our stomach. I had to do a reality check. And so now, when I go back, I have a better idea of what’s really involved and having the patience for it. But I’m going to open it up to the other panelists if they have something to share about how they’ve dealt with things they didn’t anticipate while working in the archives.

Harris: I think what you said was important. So for me now, it’s about going in and not expecting to do research right away, as soon as I get in there at 9:15, but actually talking to the archivists and the staff, and understanding the space and the protocols of that space. Because each archival space is very different. Another thing that’s important to me, if I haven’t already emailed the archivists, is to have a small sit down about what I’m working on and what I think I need. That’s important for me because I’m going to be in that space for who knows, maybe three years, four years, maybe even ten years? And I want them to know exactly at that moment what I’m doing and how my project could possibly evolve.

That way they could possibly direct me towards archival collections that I hadn’t even thought of. I focus on one particular archival collection, but there may be other archival collections that speak to what I need. And I think the third thing for me is to start small and slow. I know that sometimes when you go into the archives there’s limited time, at least for some of us, but start off small. One box may be a lot. For me it’s about starting small, getting to know the space, and talking to the people who manage that space, because I want them to know exactly what am I doing just in case a new archival collection comes in, they can send me an email and say, “Hey, we got this in. You might be interested,” or “There’s another historian, or there’s another space that you might want to consult.”

Cooper: Thank you. Anybody else want to jump in on that question?

Raquel Mirabal: Sure, I can jump in. So, I actually have a Tamiment story, and it allows us to think about the archives. When I was doing research, by 1932 there was an organization called El Club Julio Antonio Mella, organized in New York, and it was named after one of the founders of the Communist Party in Cuba. And I thought, wait a second, how did they organize an organization? So I did a lot of research, and then I found out that it was part of the IWO [International Workers Order], and so I then went to the Tamiment Library and realized that this was one of many of the immigrant lodges, what they call logia, with the IWO.

And I think what was interesting when I went to the Tamiment is that oftentimes when you do research, you realize that the librarians and the archivists might not know what you know. I would come in with my specific sense of knowledge and be like, “Oh, you must have information on this.” And the person I was working with was like, “We’ve never really heard of them.” So, it’s important to understand that they have a certain knowledge base, and you’re coming in with your specific questions.

One of the things that I realized was that there is a lot of, I don’t know if it is cross-fertilization. But I realized that this club, which is so important and valuable, and maybe the Tamiment could build up a little bit more about this club, is actually at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. They ended up having an enormous amount of information with the sources, and a lot of it had to do with the founder, Jesus Colon, who was a Puerto Rican activist in the 1920s and 1930s.

And so the story goes, “Okay, Jesus Colon is going to take me here, and then this is going to go here and so forth.” That was kind of the story. Number one is to be flexible. Number two to have these conversations. The third, that I would say is really for me, is looking at the source once was never enough. I would look at the source, and then I would do research. I would write, and then I would come back to the source, and it was almost like I was seeing a different source because of what you come with. To be conscious of that is so key.

It’s almost like layers. When you first look at a source you’re going to think about it a certain way. And then you’re going to write and research, look at the other sources, build up, make those connections, and then, when you come back, you’ll look at it a different way. So I would recommend continuing to look at those same sources. Don’t think that you’re ever finished, because you’re not. It will become much richer and more complicated as you approach those sources later on down the line.

García Merchant: One of the things we always teach our students working on the project in the classroom, wherever we’re engaging with the work, is to have that conversation with those documents. To look at them and understand why they are living documents. Why were they produced, when were they produced, how were they produced, who produced them, among all the elements that combined to create the reason that document exists? The other thing we have to look at are all of the additional information on a newspaper page. Why was that page kept? What else is going on? And this happens not just in Chicano Por Mi Raza, but the U.S. Latino Digital Humanities Center, Maas 1848, which is a project out of UNM. We’re always talking to students about engaging with the material in that way to say, “What else do you see on this page? What else do you see in this program? What other information is it telling you, and why exactly? Who saves what and why?”

Cooper: Thank you for that. I want to touch on something that’s come up in the discussions, and that also came up during our pre-planning meeting is the issue of money and funding, and how this work gets done. Can Michael and Linda to speak to it? Michael from an institutional level, and then Linda as a researcher.

García Merchant: So in my talk I talked about the fact that for eleven years we didn’t have funding, and that we couldn’t get funding. And one of the reasons we couldn’t get funding is because the institution had no inclination to accommodate us in any kind of way that made us visible. Being at Michigan was no benefit to us, and was a detriment because we could never get into any kind of institute. We’ve never done this project with any kind of funding.

I say that to say that we exist because we were just determined to exist with opportunities in building relationships in order to get what we have. That’s now shifted. I also want to clarify about student labor. All of the students that actually worked on this were compensated in some way, either in doing this as course work, getting a grade and getting that kind of experience, or working with us through institutional grants that students can get through, I think, UROP at Michigan.

Koncewicz: A lot of my friends from graduate school are historians, and I think they rely on year-to-year gigs. They often, I think, just assume that archives and libraries are just more stable, and I guess they are compared to academia. But they’re mostly unaware of the fact that an increasing number of positions within archives and libraries are contingent. Much of our work relies on adjunct’s labor and grant-funded positions. That’s always going to be an obstacle when we’re trying to plan out the future, when we’re trying to complete ambitious curatorial projects. It’s something I think the public, our community, is increasingly becoming aware of. But the broader public, I think, is not aware of it.

Cooper: Thank you. I’ll just sort of tie that up with one point we had when talking amongst the presenters is the idea of when folks have the opportunity to negotiate their positions, particularly in academia, to bring in other people through the door with them. I saw on Twitter recently how a librarian was negotiating her position, and she negotiated to have her two colleagues get new positions that had a pay raise attached to them. Just thinking about the different ways, the mutual aid of it. How can we all work together to strengthen the labor that’s behind it?

Reflections

Here are selected responses from the participants’ evaluation of the session and the chat. We hope their comments inspire you to view the recording if you haven’t already.

What were some of the things you learned or appreciated?

I appreciated hearing the various approaches to research, building archives, and teaching.

The power of archival work, who archives, what is archived, and how it is accessed.

Some of the sources mentioned, humility in archiving communities other than oneself, being careful of sources and ways to navigate silences and be speculative, helpful to hear these things reinforced

I thought Dr. Mirabal’s entire presentation was so crucial — talking about the intentionality of silences in archives and skepticism around sources — telling the story they want to tell not necessarily the whole story and the vast amount of places people can find information — branching out beyond the “classics” and looking at poetry and literature and alternative spaces for information and representation. Places where people have been able to tell their own stories.

The ideas of professional humility, speculation with silences, and understanding the history/power of archives to be able to critique them.

All of the presentations were fascinating. Kudos to everyone. I particularly have the concept of building intergenerational collectives, not collections sticking in my mind from this. I am also very excited to learn about the work being done at the Tamiment Library, which I didn’t know existed until now. I am also inspired by the determination of Dr. Harris and Dr. Mirabal to navigate the silences and stick with projects to tell stories of people who have been silenced through the record. Thanks!

The initial resources shared by Linda García Merchant will be of great use to my HS US History students!

Importance of involvement of oppressed communities, humility, and self-critical approach to historical techniques.

That there are many archives of stories, there are still many stories missing and there are stories that aren’t told in those existing archives in a non stereotypical manner.

The immense challenges of both preserving and processing archival materials

“Silences in the archives are often deliberate.”

I really appreciated Lauren’s presentation showing how to center their principles and stories before “professionalism”. All of the presenters were EXCELLENT. Nancy’s presentation was also insightful of how to get started when you might not have access to the information you’re looking for.

The discussions of navigating the silences were important, especially the repeated discussions on how art, poetry, music, etc. can help us to fill those silences and better understand the past. I also especially enjoyed hearing about how our perspectives, even on a singular source, can change over time as we read other materials, engage with other sources, and shift our perspective.

I was simply inspired by the number of dedicated people in the field researching peoples’ history and making it accessible.

I loved the concepts of thinking about what IS NOT in the archive, starting slowly, exploring adjacent or even unrelated archives, and utilizing materials other than primary source documents — like songs, objects, fiction, etc.

I learned that archives are not apolitical and that archives are intentionally curated. More specifically, archives and archivists have the power to either prove and preserve the existence of certain individuals, groups, communities, ideas, etc. or participate in the silencing and erasure of said individuals, groups, communities, ideas, etc.

Comments on Overall Session

I enjoyed this a lot. I’d love to see a “Radicalizing Archives” conference or unconference or at least a session at an existing conference. The conversations could potentially go deeper.

The content for today’s “Radicalizing the Archive” session was rich, accessible, and relevant! Also, I really appreciated the opportunity to listen, then stop and jot, and verbally process my ideas/listen to others in a small group, while also being able to share information in the chat. I also am grateful that there were ASL interpreters to help ensure today’s session was accessible to a wider audience base.

I thought this whole session was really interesting and engaging. I especially liked the format of the Google Docs to collect thoughts before the breakout sessions.

The work that archivists are doing is amazing and I loved the speaker who talked about approaching the material in multiple time frames to experience how her perception changed since her first contact with the material.

Thank you for such great presentations. I appreciate especially your sharing of the goals, journeys, and lessons learned. Very inspiring!

Thank you for the wonderful programming — as always. I always leave a little bit smarter (smile).

Learn More

Find additional resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn