Below is our growing collection of stories from educators who are teaching people’s history remotely during the pandemic.

If you have your own stories to share, tell us and we can send you a people’s history book in appreciation.

. . . I had previously bagged the writing assignment I had created for that day and instead used the poem “Wash Your Hands” by Dori Midnight, which I discovered on Facebook. The poem takes the “wash your hands” mantra and turns it into a meditation on this moment — a song, a political stance, a prayer, advice, a rant. A perfect piece for our first meeting during the tidal wave of pandemic news, panic, and closures. . . .

After reading the poem together, I said, “Please take a few minutes to reread the poem. Mark it up. Look for style and content. Also, highlight places that you think could be jumping off places for our writing — lines, phrases, ideas.” When reading a piece in the Oregon Writing Project, our mantra is “raise the bones.” . . . Continue reading at Rethinking Schools

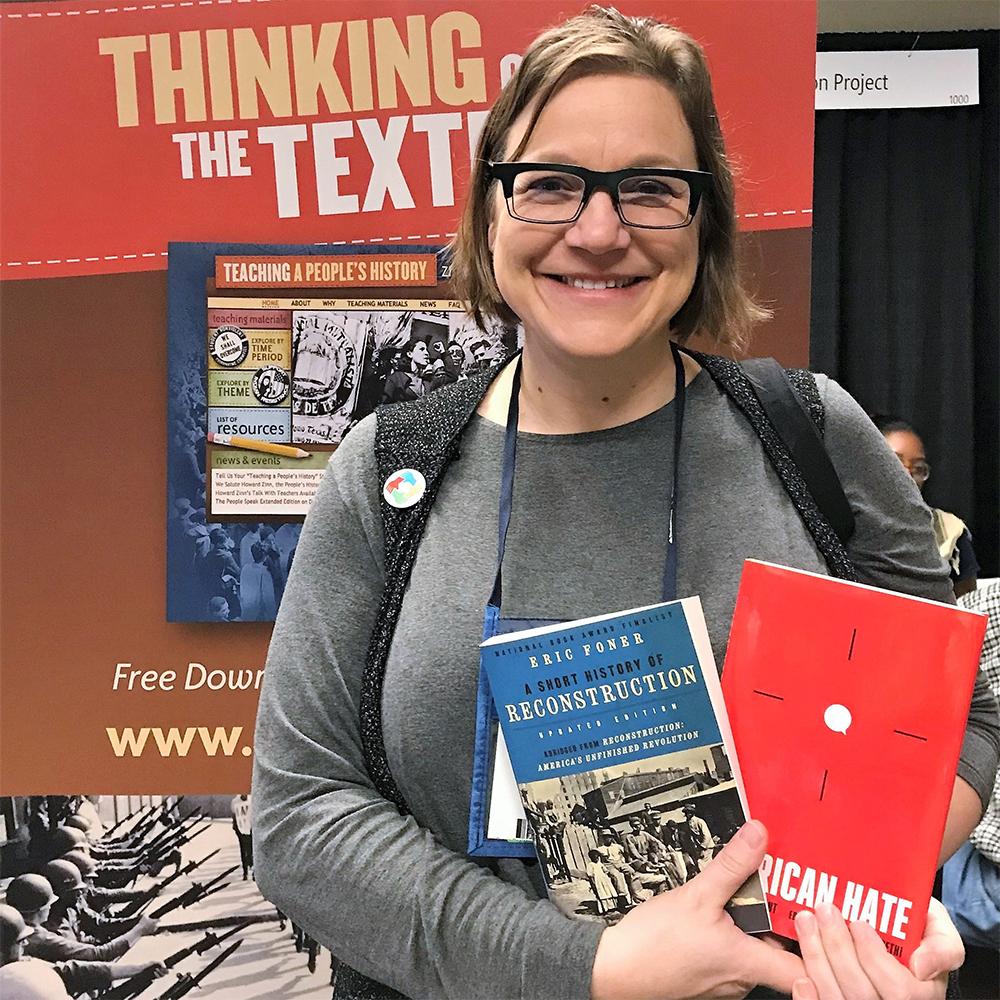

Adapting Adam Sanchez’s lesson, Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted, for online learning was a labor of love. The Rethinking Schools/Zinn Education Project’s mixer activities have been a catalyst for understanding in my classroom; I couldn’t imagine any space — even at a distance — that didn’t include that power.

The first hurdle to overcome was the difference in participation between a captive audience in class and students logging in when they can at home. There are the logistics of asynchronous participation which come from any online learning scenario. And there is particular care to be taken specifically during the COVID-19 outbreak, when families are experiencing stress and upheaval at home. . . . Continue reading

I have been using Zinn Education Project materials for about two years now and the role plays and mixers from this website have been my absolute favorite lessons I teach throughout the year. I love how detailed each of the steps are, with real student thoughts and answers, so I can predict how my students might react and problem solve.

I found this website with a search to replace the more typical Constitutional Convention simulation. I had previously assigned roles of the signers to my students, given them placards with information about their views, and then left it up to the students to debate what they thought should be the new rules of our country. I was unsatisfied with this because my students just did not have the depth and historical background to take on the role of a specific person in history. Their arguments were limited to the research they had been given. That’s where the Zinn Education Project is different. Instead of focusing on these specific men, my students were able to see through the eyes of groups of people. They were given the understanding they needed to argue for what would benefit their role the most. The arguments came from a place of understanding and quickly my students had extremely meaningful conversations about how we should hold power in our country and why.

Obviously, that simulation was completed in the classroom and I did several more throughout the year which gave students more confidence to understand the flow of history as they saw groups like merchants and farmers repeated over and over. They were able to guess how that group might respond without even reading the description page.

Since the time of “distance learning” I have completed the Reconstructing the South: A Role Play which asks students who have learned about the fight for freedom during the Civil War, to decide what THEY would want at the end. I gave them the questions ahead of time and several days to thoughtfully read through and make their own decisions. Then, on our day of live class, with just me prompting the questions, they lead a thoughtful discussion of what they wanted but also what they thought would be reasonable to ask for. They appreciated a way for us to digitally discuss issues that are important, even when we couldn’t be together. In fact, we hadn’t finished all of the scenarios when our time was up and they begged to do more!

I am just so thankful to these FREE resources and the many articles that have pushed my own thinking as a teacher. Thank you!

Every year, in my U.S. history class, my students do the U.S. Mexico War mixer. My students have a lesson on the war and, through readings and lecture, are encouraged to see the war from many perspectives, including the Mexican perspective of the war as a “War of Dismemberment,” in which Mexico lost one-third of its territory to the United States in a conflict provoked by the Polk administration. The mixer provided a great way for students to jump more in-depth into trying on the various perspectives of people affected by the war.

During the pandemic, I didn’t want our district’s move to “distance learning” to deprive my students of valuable lessons in people’s history, so I taught a modified version of the mixer. Fortunately, my students have school-issued laptops, access to the G-apps suite, and (as far as I am aware) decent access to broadband internet.

Using Google Classroom, I posted the variety of roles in a .pdf for students to access and asked them to complete the worksheet provided in which they had to “meet” a variety of figures. If we had more time to spend on this lesson, I could see myself making a more robust version, where the students are assigned roles — as they traditionally were in the normal classroom version — and then post videos of themselves introducing themselves on FlipGrid or “meeting” in groups using Zoom.

I won’t let the challenges we are presented with stop me from allowing my students access to meaningful lessons in social studies that integrate principles of human rights and social justice.

The U.S. Mexico War mixer was a little bumpy, but it got better when we tried breakout rooms, which was exactly what the students needed. The students made a good set of collective notes that will help them connect the mixer lesson with their upcoming reading assignment. This online lesson gave me ideas for how to prepare for our upcoming lessons.

I’m starting the Election of 1860 Role Play with my 10th graders and will do the Seneca Falls lesson next with 9th, once they finish reading “We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God” and respond to some questions.

I feel a lot of sadness, but I am also inspired and motivated by the opportunities to connect my students to such meaningful learning.

Read a full-length article about how Bethany Hobbs taught the U.S. Mexico War mixer lesson.

My IB anthropology class is discussing a mini ethnographic project that would examine aspects of the coronavirus crisis — how people are coping, what the ripple effects are, whom it’s hurting most, what it says about how our society works. It’s just a very important learning moment.

We are also focused on being compassionate, recognizing students may be helping their families get through a tough time or be struggling with anxiety. It’s an overwhelming time for students. If we give one meaningful assignment or project in a week, or in two weeks, I think that it’s more worthwhile than busy work. It’s such an abnormal situation that we can’t follow normal protocols.

I am an ELA and Social Studies teacher, and because of the lack of emphasis on teaching Social Studies in my state (it is not a tested subject in Pennsylvania), I try to teach my courses as one, large, humanities style course.

While school is out during the global pandemic, I made an Instagram account that my students can follow where I post daily updates and assignments. Everything from “share one thing you are thankful for today, during this scary time,” to giving words and definitions and having students write their own sentences in the comments using the word, to sharing clips from my calendar of a history of racial injustice in the United States.

Right now, my students are working on a research paper about a person who was persecuted but persevered in history, such as Yuri Kochiyama, Elie Wiesel, Claudette Colvin, etc. I am using Instagram’s interactive actions such as the response box to get students to share their research subject’s stories as they do research and interact with each other and ask each other research questions. Additionally, we are also learning about the history of mass incarceration in the United States and I am using Instagram to share articles about voting rights for incarcerated people, and important statistics and graphics from places like The Sentencing Project.

Every day, I try to post two to three “assignments” that ask students to interact with a post (today they read an article about voting rights for incarcerated people and had to post their opinion citing evidence as to why they had that opinion), as well as six to ten stories sharing interesting tidbits and asking for responses/actions on the stories.

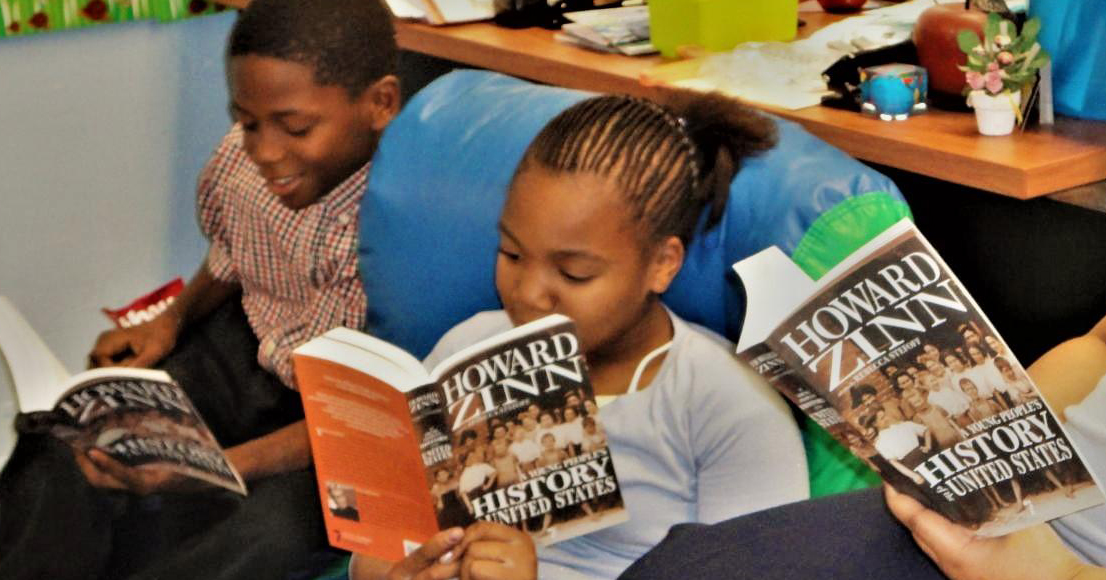

I currently teach 7th and 8th graders at a small, private Montessori school in Nashville, Tennessee. We have just wrapped up our first week of remote learning, now that my district schools are closed because of the pandemic. My co-teacher and I are using Google Classroom and Zoom as our main technological tools. It’s our year to teach U.S. history and we have been using A Young People’s History of the United States.

In teaching about the coronavirus, I plan on using the two articles shared in a Zinn Education Project newsletter, about the connection between deforestation, climate change, and coronavirus. Also, earlier this year, we read Fever 1793, and I plan on returning to that, so we can make connections between yellow fever in the 1793 United States and current conditions.

We are currently teaching Reconstruction and, when we get to the Civil Rights Movement, I plan to use the adapted versions of two Zinn Education Project articles — What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should and The Other ’68: Black Power During Reconstruction — at Newsela.

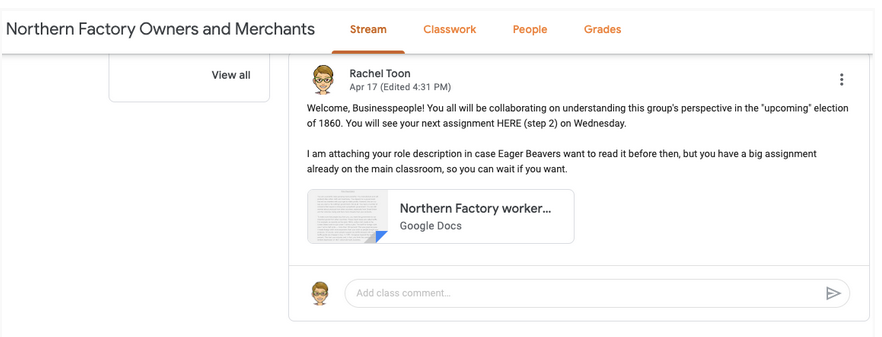

Bill Bigelow’s lesson, The Election of 1860 Role Play, offers a meaningful and memorable way for students to learn about the sectional tensions leading up to the Civil War. I knew I had to dive into the daunting waters of doing a full-on role-play in this distance learning context and offer a step-by-step article to describe how I did it.

Google Classroom screenshot from my lesson. I created five new Google Classrooms and titled them with the mixer roles. My first posts in each of the roles Classrooms were to get the students acclimated to the new Classrooms and jump-start their conversations.

I have organized a walk-through of this lesson with Bill’s words from the original lesson, with my slides and rationale for adaptation. . . . Continue reading “Teaching People’s History Online: The Election of 1860”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn