By Jeff Biggers

Today is Coal Miner’s Day — or used to be: October 12th marks the day a small band of striking coal miners in southern Illinois called out Chicago coal barons and stood their ground at Virden in 1898. By the end of the day, seven miners lay dead, but the strike-breaking barons had been stopped. For most historians, the defiance of union coal miners at the Virden Massacre marked the turning point in the labor movement, impacting the lives of untold thousands of laborers over the next century.

“When mining began,” noted a U.S. Coal Commission report in the 1920s, examining the conditions before the union movement in 1897, “it was upon a ruinously competitive basis. Profit was the sole object; the life and health of employees was of no moment. Men worked in water half-way up to their knees, in gas-filled rooms, in unventilated mines where the air was so foul that no man could work long without seriously impairing his health. There was no workmen’s compensation law, accidents were frequent. . . The average daily wage of the miner was from $1.25 to $2.00.”

Francis Peabody, the namesake of the world’s largest coal company today, called it “survival of the fittest.”

Miners not only lived and worked in deplorable conditions, they were also subjected to the whims of the market, often out of work for the long summer months, and forced to migrate for poorly paid day labor. Displaced and unorganized, the miners faced a situation of extreme vulnerability. They often lived in company-owned houses, held in debt, compelled to patronize company-owned shops, and were paid in a company script only valid at company businesses.

To address this miserable situation, the United Mine Workers of America called for a general strike across the nation in 1897. Founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1890, they counted less than four hundred members in Illinois. Little did the district leaders know that a flamboyant thirty-one-year-old miner in southern Illinois, a veteran of hunger marches on the nation’s capitol in Washington, DC, in 1894, would don a silk top hat, a Prince Albert topcoat, and an umbrella and declare himself “General” Alexander Bradley.

Bradley led marches from mine to mine in southern Illinois in a crusade to unionize the workers. Thousands of miners swept across the coalfields, attentive to Bradley’s spellbinding speeches and flashy attire and assisted in setting up a union vote. He forbade any violence. And the mines unionized. By the end of 1897, the union ranks grew from 400 to over 30,000. With the backing of the militant southern Illinois contingent, the United Mine Workers ironed out a deal with coal operators for an eight-hour day, a six-day week, major concessions for better working conditions, and a 30 percent increase in wages.

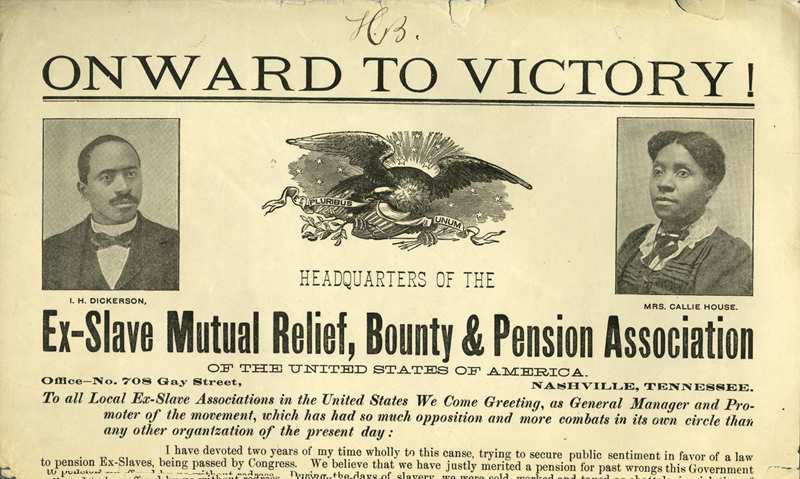

Bradley’s rank and file, though, and the United Mine Workers nationwide, were tested later that year. While the “General” and the UMWA had successfully bridged ethnic differences among various European and non-English-speaking miners, the Chicago-based company for a mine in Virden, Illinois, looked south of the Mason-Dixon Line for an old tactic of division. Recognizing that Black laborers had been used in the mines in Alabama and Tennessee — many in a decades-long scandal of convict labor, or rather, laborers who had been framed for minor offenses and sent to the coal prison labor camps — the Chicago company sent a recruiter to Birmingham, Alabama, to hire non-union Black coal miners to break Bradley’s strike.

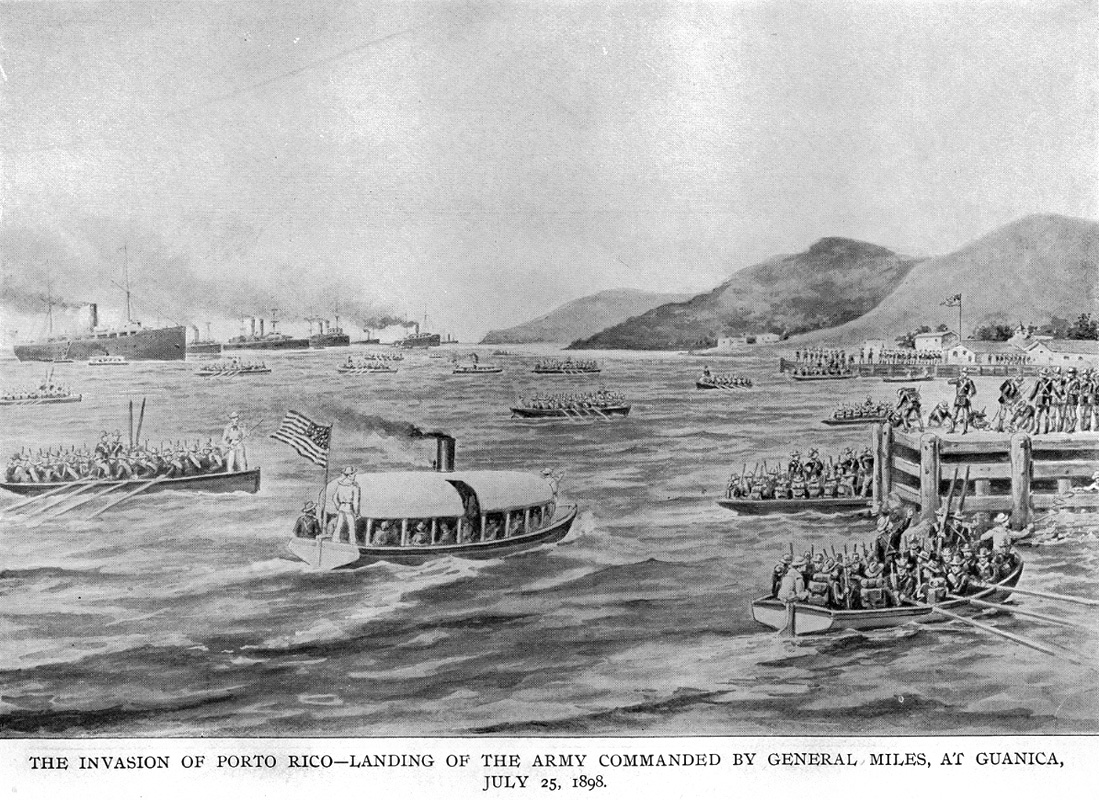

The Black coal miners were mistakenly told that the regular miners had left their jobs to serve in the Spanish-American War. They boarded the trains. So did their armed escorts, Thiel Detective Service agents out of St. Louis.

The coal barons’ intentions were clear — they planned to test the mettle of the striking union and the resolve of the governor. In the coal company’s mind, the lives of the strikebreakers were as expendable as the miners.

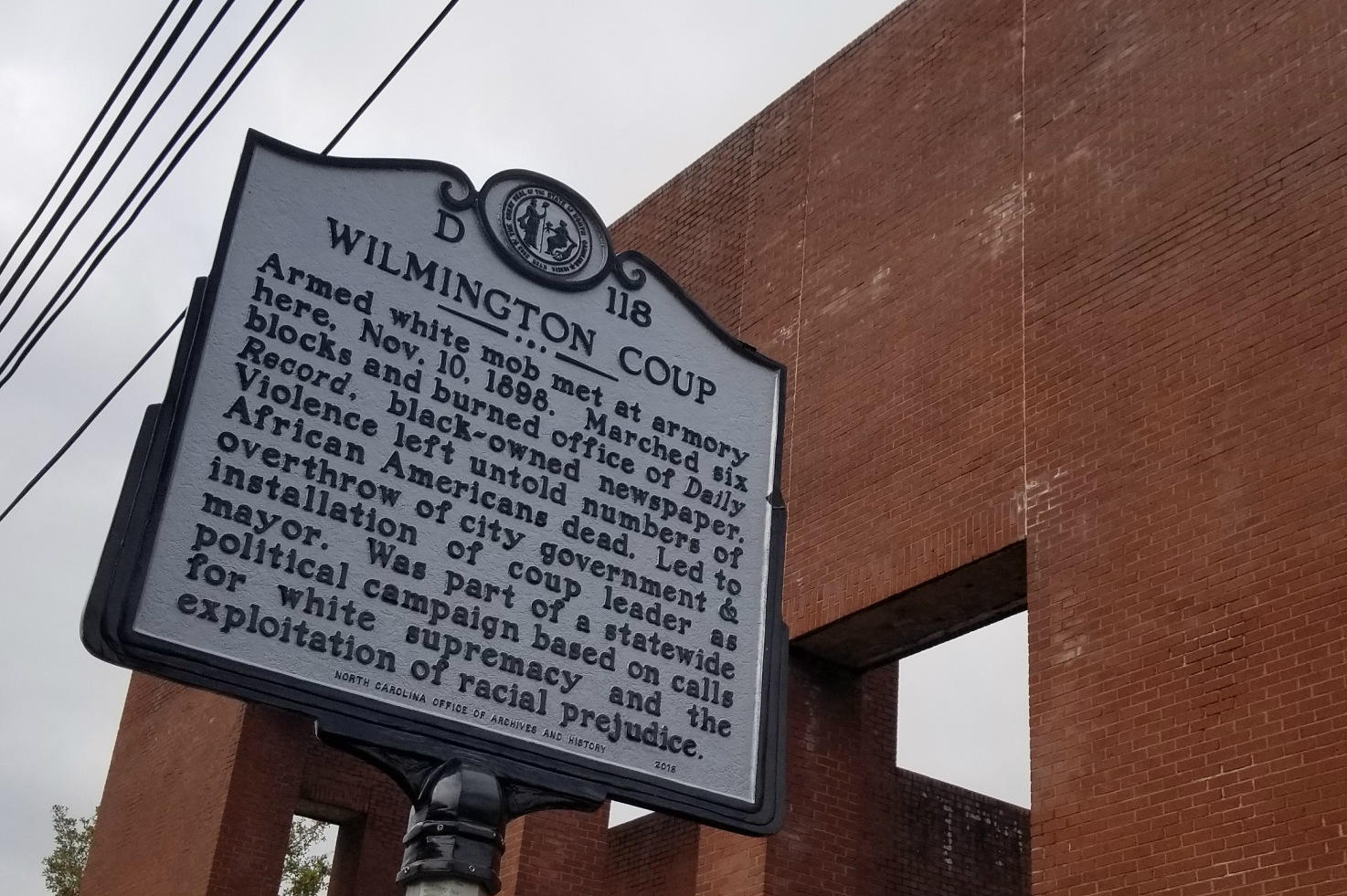

When the escorted strikebreakers arrived at an armed stockade set up near the train station in Virden around midday on October 12, 1898, a shootout erupted. It lasted ten minutes. The company gunmen overpowered the strikers with their modern Winchester rifles; the striking miners returned fire with shotguns and hunting rifles. Twelve men were killed; seven were miners, five were armed guards. Forty strikers were wounded. None of the Black strike-breakers were wounded. The National Guard arrived several hours later. The governor’s inaction was ultimately denounced across the country.

While some of the strikebreakers stayed and found work in the mine or joined the union, Bradley’s defiance and protest against Virden rang out across the country as a bellwether of the union movement’s resolve. They had held the line. Within seven years, the holdout Carterville coal operator declared bankruptcy and negotiated with the union.

The absentee coal operatives also played this divisive race card in nearby Pana and Carterville. The United Mine Workers had been founded as an integrated union — one of the few in the nation at the time. And although African Americans eventually took leadership roles in southern Illinois and accounted for nearly 15 percent of the union ranks by 1900, the overall effect of the deceitful political ploy and subsequent infusions of outside Klan operatives would have repercussions for decades to come.

In her memoirs, civil rights activist and educator Helen Bass Williams, who grew up in the segregated Black coal camps of Dewmaine and Colp near Carterville, recounted the constant attacks by racist mobs when African American miners joined the union. Houses were burned to the ground; whole families hid in the woods. Williams’s maternal grandfather had escaped the convict-leasing system of slavery in Coal Creek, Tennessee, after coal miners went on strike in 1891. Her father ended up serving as the secretary of the local office of the United Mine Workers in southern Illinois.

At her request, the nation’s coal miners buried Mother Jones at Mount Olive in the south-central Illinois coalfields — the burning ground of unionism — at the only Union Miners’ Cemetery in the nation. It had been established after the Virden battle, when a Mount Olive church refused to inter the bodies of the seven strikers. A local coal miner raised the money to buy the plots, which soon spread across the fields; an arching gate declared it the terrain of union miners.

“When the last call comes for me to take my final rest,” Mother Jones had written, “will the miners see that I get a resting place in the same clay that shelters the miners who gave up their lives on the hills of Virden, Illinois. . . They are responsible for Illinois being the best organized labor state in America. I hope it will be my consolation when I pass away to feel I sleep under the clay with those brave boys.”

Alexander Bradley died in 1918 from black lung disease, having returned to the mines as a front loader. His role in building the United Mine Workers disappeared from most history texts. But the militant southern Illinois mine workers had become the most powerful vanguard in the union movement and churned out new generations of leaders.

And coal mining communities in southern Illinois today, under a new onslaught of coal barons like Cline, remember his legacy.

_______________________________________

Jeff Biggers is author of Reckoning at Eagle Creek: The Secret Legacy of Coal in the Heartland and Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition

Excerpted and reprinted with permission of Jeff Biggers from Mother Jones Is Still Calling Out Deadbeat Coal Barons (on Coal Miner’s Day), October 12, 2010 in the Huffington Post.

Learn more from “Remember Virden: The Coal Mine Wars of 1898-1900” by Rosemary Feurer from Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO).

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn