From May 1-3 in 1866, white civilians and police killed 46 African Americans and injured many more while burning houses, schools, and churches in Memphis, Tennessee.

No criminal proceedings were held for the instigators or perpetrators of atrocities committed during the Memphis Massacre (also referred to as the Memphis Riot). Here is a description of the riot in historical context by Lerone Bennett Jr. from Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America (pages 224 – 226):

The land problem was linked to the larger problems of the South and the status of Blacks. Nothing could be done with the conquered South until the status of Blacks was settled. The reverse was also true. Nothing could be done for Blacks until the status of the conquered South was settled. Lincoln’s answer to this problem was liberal to the South. He wanted to readmit the Southern states as soon as 10 percent of the prewar electorate had qualified by taking an oath of allegiance to America. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, was substantially of the same mind. Neither man came to grips with the status of Blacks, although Lincoln suggested that “very intelligent” Blacks and Union veterans be given the right to vote.

[Thaddeus] Stevens and [Charles] Sumner were aghast at the presidential innocence. To turn the former slaves over to their former master without adequate safeguards, they contended, would be madness. It was soon apparent that their apprehensions were all too well founded. For the conservative provisional governors appointed by President Johnson organized lily-white governments with blatant proslavery biases. In 1865 and 1866 these governments enacted the Black Codes which indicated that the South intended to reestablish slavery under another name. The codes restricted the rights of freedmen under vagrancy and apprenticeship laws. South Carolina forbade freedmen to follow any occupation except farming and menial service and required a special license to do other work. The legislature also gave “masters” the right to whip “servants” under eighteen years of age. In other states Blacks could be punished for “insulting gestures,” “seditious speeches” and the “crime” of walking off a job. Blacks could not preach in one state without police permission. A Mississippi law enacted late in November required Blacks to have jobs before the second Monday in January.

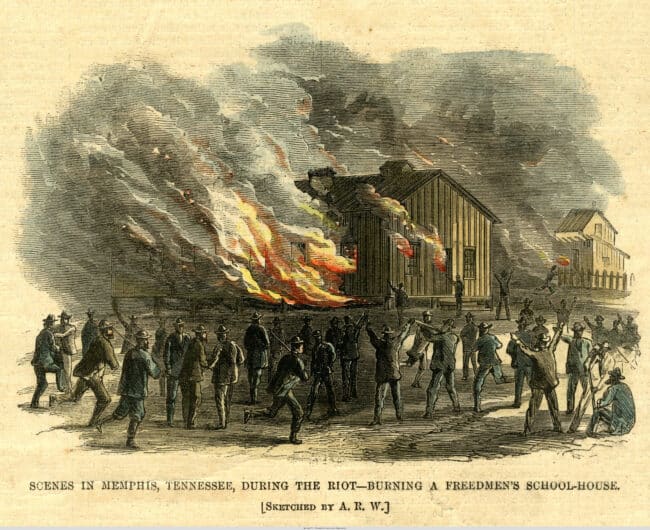

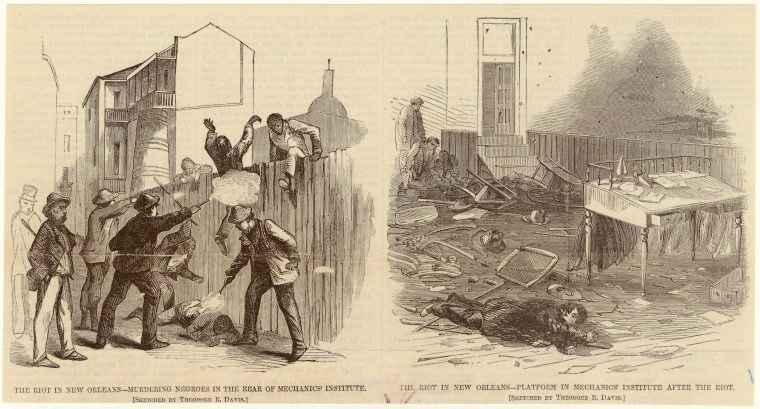

Illustration in Harper’s Weekly of the Memphis Riot of 1866 Alfred Rudolph Waud; Harper’s Weekly, 26 May 1866 – Tennessee State Library and Archive.

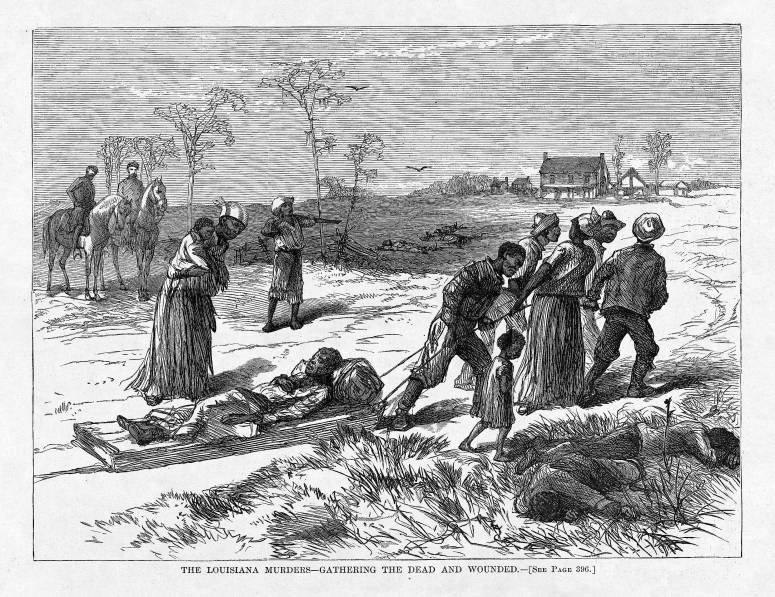

Even more serious was the vindictive attitude of Southerners, who vented their frustration on unarmed Blacks. Gen. Carl Schurz, who made a special investigation for the president, was astonished by postwar conditions in the South. “Some planters,” he said, “held back their former slaves on their plantations by brute force. Armed bands of white men patrolled the country roads to drive back the Negros wandering about. Dead bodies of murdered Negroes were found on and near the highways and by-ways. Gruesome reports came from the hospitals—reports of colored men and women whose ears had been cut off, whose skulls had been broken by blows, whose bodies had been slashed by knives or lacerated with scourges. A number of such cases, I had occasion to examine myself. A . . . reign of terror prevailed in many parts of the South.”

Throughout this period, and on into the 1870s, hundreds of freemen were massacred in “riots” staged and directed by policemen and other government officials. In the Memphis, Tennessee, “riot” of May 1866, forty-six Blacks (Union veterans were a special target) were killed and seventy-five were wounded. Five Black women were raped by whites, twelve schools and four churches were burned. Two months later, in New Orleans, policemen returned to the attack, killing some forty Blacks and wounding one hundred.

“The emancipation of the slave,” General Schurz concluded, “is submitted to only in so far as chattel slavery in the old form could not be kept up. But although the freedman is no longer considered the property of the individual master, he is considered the slave of society. . . . Wherever I go—the street, the shop, the house, the hotel, or the steamboat—I hear the people talk in such a way as to indicate that they are yet unable to conceive of the Negro as possessing any rights at all. Men who are honorable in their dealing with their white neighbors will cheat a Negro without feeling a single twinge of their honor. To kill a Negro, they do not deem murder; to debauch a Negro woman, they do not think fornication; to take property away from a Negro, they do not consider robbery. The people boast that when they get freedmen’s affairs in their own hands, to use their own expression, ‘the niggers will catch hell.’”

All of these factors—Southern intransigence and arrogance, the Black Codes, the Memphis and New Orleans “riots” – changed the national mood. Here and there, men fell into step with Sumner and Stevens. They did so for many reasons. Some believed it would be a major tragedy to hand the freedmen over to their former masters. Others saw a chance to insure the continued supremacy of the Republican party. Still others believed it would be dangerous to return ex-Confederates to national power. For various reasons, some of them contradictory, some of them noble, some of them base, people began to march by the sound of a different drummer.

Read more in this detailed thread from Professor Shawn Leigh Alexander:

Remembering Reconstruction: The Memphis Massacre of 1866 #TeachReconstruction #ReconstructionPBS @MemphisMassacre #MemphisMassacre1866 pic.twitter.com/qMB8xWlKv9

— Shawn Leigh Alexander (@S_L_Alexander) May 3, 2019

Alexander alerted us to “A History They Can Use: The Memphis Massacre and Reconstruction’s Public History Terrain” by Susan O’Donovan and Beverly Bond and he recommends reading Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (UNC Press, 2009) by Hannah Rosen. Also, Remembering the Memphis Massacre: An American Story.

The Memphis Massacre is one of countless massacres in U.S. history and one of many key stories from the Reconstruction era of the United States history.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn