Author Mickey Z begins with Thomas Paine’s revolutionary manifesto “Common Sense,” written anonymously as a pamphlet in January 1776 and read by every member of Congress, and goes on to highlight notable people and events in the history of the United States. Here are a few of the historic events described in short essays in this pocket-sized book:

Author Mickey Z begins with Thomas Paine’s revolutionary manifesto “Common Sense,” written anonymously as a pamphlet in January 1776 and read by every member of Congress, and goes on to highlight notable people and events in the history of the United States. Here are a few of the historic events described in short essays in this pocket-sized book:

- Shays’ Rebellion (see excerpt below)

- The Seminole-African alliance

- Lizzie Jennings Gets on the Bus (see excerpt below)

- Helen Keller opposes U.S. involvement in World War I

- The Bonus Army demands justice

- Lester Rodney helps break baseball’s color line

- Salt of the Earth is filmed

- I.F. Stone goes Weekly

- American Indians Occupy Alcatraz Island

- Public Enemy fights the power

- Families of 9/11 victims say “no” to revenge

In addition to concise essays, Mickey also highlights important milestones along the timeline of the book. [Publisher’s description.]

ISBN: 9781932857184 | The Disinformation Company

Sample entries

Shays’ Rebellion

Soldiers fire on protesters during Shays’ Rebellion. Led by Daniel Shays, a group of poor farmers and Revolutionary War veterans attempted to shut down Massachusetts courts in protest against debt collections against veterans and the heavy tax burden borne by the colony’s farmers.

Long before the cries of “support the troops” became commonplace during every U.S. military intervention, the powers-that-be made it clear how much they intended to follow their own advice.

“When Massachusetts passed a state constitution in 1780, it found few friends among the poor and middle class, many of them veterans from the Continental Army still waiting for promised bonuses,” explains historian Kenneth C. Davis. To add to this, excessive property taxes were combined with polling taxes designed to prevent the poor from voting. “No one could hold state office without being quite wealthy,” Howard Zinn [in A People’s History of the United States] adds. “Furthermore, the legislature was refusing to issue paper money, as had been done in some other states, like Rhode Island, to make it easier for debt-ridden farmers to pay off their creditors.”

Perhaps heeding the advice of Thomas Jefferson that “a little rebellion” is necessary, Massachusetts farmers fought back when their property was seized due to lack of debt repayment. Armed and organized, their ranks grew into the hundreds. Local sheriffs called out the militia. . . but the militia sided with the farmers. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts indicted eleven members of the rebellion. Those who had so recently fomented revolt were no longer tolerant of such insurrection.

Enter Daniel Shays (1747-1825): Massachusetts farmer and former Army captain. He chose not to stand idly as battle lines were being drawn and friends of his faced imprisonment. In September 1786, Shays led an army of some 700 farmers, workers, and veterans into Springfield. “Onetime radical Sam Adams now part of the Boston Establishment, drew up a Riot Act,” says Davis, “allowing the authorities to jail anyone without a trail.” Shays’ army swelled to more than 1,000 men.

Writing from Paris, Jefferson offered tacit approval for, at least, the concept of rebellion. Closer to home, the American aristocracy was less than pleased. Sam Adams again: “In monarchy, the crime of treason may admit of being pardoned or lightly punished, but the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death.”

In a classic shape-of-things-to-come scenario, Boston merchants pooled money to raise an army to be led by General Benjamin Lincoln, one of George Washington’s war commanders. Clashes were fierce but the outnumbered rebels were on the run by winter. Most were killed or captured. Some were hanged while others, including Shays, were eventually pardoned in 1787.

Shays died in poverty and obscurity, but the rebellion he helped lead not only served as a example of radical patriotism, it resulted in some concrete reforms including, as Davis states, “the end of direct taxation, lowered court costs, and the exemption of workmen’s tools and household necessities from the debt process.”

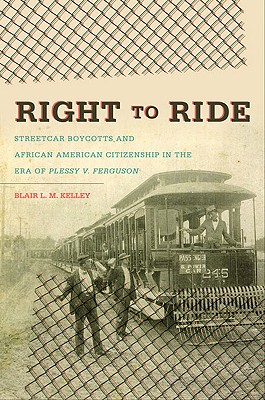

Lizzie Jennings Gets on the Bus

Elizabeth Jennings Graham, ca. 1895.

On July 16, 1854, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jennings (1830-1901), a 24-year-old schoolteacher setting out to fulfill her duties as organist at the First Colored Congregational Church on Sixth Street and Second Avenue, fatefully waited for the bus on the corner of Pearl and Chatham. Getting around 1854 New York City often involved paying a fare to board a large horse-drawn carriage, the forerunner to today’s behemoth motorized buses. For black New Yorkers like Jennings, it wasn’t that simple.

Pre-Civil War Manhattan may have been home to the nation’s largest African-American population and New York’s black residents may have paid taxes and owned property, but riding the bus with whites, well, that was a different story. Some buses bore large “Colored Persons Allowed” signs, while all other buses — those without the sign — were governed by a rather arbitrary system of passenger choice. . .

Against such a volatile backdrop, Lizzie Jennings opted for a bus without the “Colored Persons Allowed” sign. The New York Tribune described what happened next: “She got upon one of the Company’s cars on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted.” . . .

This would not be the end of it for, like Rosa Parks, Jennings’ behavior was no impetuous act of resistance. “Jennings was well connected,” says Williams. “Her father was an important businessman and community leader with ties to the two major black churches in the city.” Not satisfied with the massive rally that took place the following day at her church, Elizabeth Jennings hired the law firm of Culver, Parker & Arthur and took the Third Avenue Railway Company to court.

In a classic “who knew?” situation, Jennings was represented by a 24-year-old lawyer named Chester A. Arthur — yes, he who would go on to become the 21st president upon the death of James A. Garfield in 1881. The trial took place in the bus company’s home base of Brooklyn — then a separate city — where, in early 1855, Judge William Rockwell of the Brooklyn Circuit Court ruled in the black schoolteacher’s favor.

By 1860, all of the city’s street and rail cars were desegregated.

Learn More

The two articles below include more information about Lizzie Jennings, including the fact that abolitionist and newspaper publisher Frederick Douglass helped publicize her case and noted abolitionists such as Henry Highland Garnet were involved in the struggle to challenge racist policies and practices on streetcars. Sadly, Jennings’ life was connected to another major historic event, the Draft Riots. During the Draft Riots, her one-year-old son died.

- The Schoolteacher on the Streetcar by Katharine Greider, New York Times, Nov. 13, 2005.

- Elizabeth Jennings in “Early African New York,” Columbia University.

Racism is endemic. Another example of Black people being served another helping of injustice.

And there are some that still say that everyone is on a level playing field. Black people in this country are continually done a disservice.