With the release of the Universal Pictures film, The Lorax, based on Dr. Seuss’s classic “environmental” book of the same name, we share an article by Bill Bigelow about the lessons children learn (and don’t learn) from the book and film about the causes of environmental ruin and how to organize for change. The article first appeared in Rethinking Schools magazine in the early 1990s. Rethinking Schools published a blog on March 1, 2012 extending this critique to the Universal Pictures release of the film by the same name. Read here.

With the release of the Universal Pictures film, The Lorax, based on Dr. Seuss’s classic “environmental” book of the same name, we share an article by Bill Bigelow about the lessons children learn (and don’t learn) from the book and film about the causes of environmental ruin and how to organize for change. The article first appeared in Rethinking Schools magazine in the early 1990s. Rethinking Schools published a blog on March 1, 2012 extending this critique to the Universal Pictures release of the film by the same name. Read here.

By Bill Bigelow

What is a good society, and how can we bring it about? Tackling these not-so simple questions was the goal of “Literature and Social Change,” a class I taught for several years at Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon.

One of our texts was The Lorax, by Dr. Seuss. On first reading, The Lorax appears to be a straightforward tale about the horrors of pollution and the necessity to become aware of nature’s interconnectedness. Although the book chronicles an environmental holocaust, the story ends on a hopeful note, with a redemptive speech from the formerly evil Once-ler. The earth and its creatures are given another chance to live a sane and ecological life. With luck, we may live happily ever after.

Indeed, The Lorax offers wonderful potential to provoke students to think about environmental degradation — from the rape of the ancient forests to the Exxon Valdez oil spill. As many educators have noted, discussing The Lorax can encourage students — even young children — to see themselves as environmental activists in their own communities.

In class we read The Lorax as serious political literature, just as we approached Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. On this level, The Lorax is flawed, offering a misleading analysis of environmental ruin and a wrong-headed — albeit implicit — strategy for social change.

I know what you’re thinking: What’s this guy’s problem, picking on Dr. Seuss? The answer is twofold: First, it’s the very simplicity of Dr. Seuss’s story that offers students such a fine opportunity to hone their skills for social analysis. And second, just because literature is simple does not make it any less influential. Books like The Lorax are read to children over and over; even if the kids don’t grasp every nuance, the books play a major role in explaining a larger world and shaping how children respond to it.

Together, students and I read and critiqued The Lorax. The students’ assignment was to rewrite Dr. Seuss’s book incorporating a more accurate analysis of the causes of environmental degradation and a vision of how change might occur.

The Environment According to Seuss

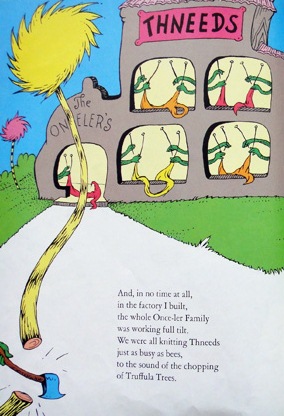

For Dr. Seuss, the root of ecological destruction is greed. The Once-ler comes to the land of Swomee-Swans and Grickle-grass, cuts down a Truffula Tree, knits his first Thneed, which “some poor stupid guy” buys, builds a Thneed factory, and he’s off on his first million. There is no competition and there are no other Thneed factories, just one greedy Once-ler. And as thneed sales feed his lust for wealth, technology must keep pace. He invents a Super-Axe-Hacker to chop down four Truffula trees at a time.

For Dr. Seuss, the root of ecological destruction is greed. The Once-ler comes to the land of Swomee-Swans and Grickle-grass, cuts down a Truffula Tree, knits his first Thneed, which “some poor stupid guy” buys, builds a Thneed factory, and he’s off on his first million. There is no competition and there are no other Thneed factories, just one greedy Once-ler. And as thneed sales feed his lust for wealth, technology must keep pace. He invents a Super-Axe-Hacker to chop down four Truffula trees at a time.

In their rewrite of Seuss, three of my students, Holly Allen, David Berkson, and Rebecca Willner, tried to portray the Truffula Tree genocide more systematically. They wanted to show that the massive whacking of trees wasn’t caused simply by the Once-ler’s greed, but derived from the way the system was constructed:

He’d come in and built up

A system of power

That made everything nasty

and yucky and sour.

This system, this network,

was based upon gain,

Where few reaped the profits

While most suffered pain.

In class we had discussed how blaming personal greed may appear to be a convenient shorthand way of explaining environmental ruin, but it’s misleading. For example, clear cutting — chopping down whole forests at a time — in the Pacific Northwest, results in major ecological damage. However, the root of this destruction is not purely personal or corporate greed. If the Weyerhaeuser Once-ler decided to abandon clear cutting in favor of selective cutting, the Louisiana-Pacific Once-ler would surely undersell Weyerhaeuser and force it out of business or back to clear cutting. Also, according to one estimate, lumber companies’ export of whole logs yields a profit of over 60 percent, compared to 10 percent producing lumber for the domestic market. What wood-products corporation could unilaterally forgo log exports and hope to compete? Massive deforestation in the Northwest is best explained as a result of the functioning of the capitalist system itself, not of individual greed.

My students felt their way toward a more structural analysis, but had trouble shaking Dr. Seuss’s narrow focus on the Once-ler’s selfish motives. They ended up asserting, rather than showing, the systematic pressures making “everything nasty and yucky and sour.”

The Once-ler and the Workers

But when it came to portraying the process of producing Thneeds, Holly, Becky and David broke decisively with Dr. Seuss. In Seuss’s The Lorax, the Once-ler hires all his brothers, uncles, and aunts to become his work force. The choice allowed Seuss to ignore the hazards and divisions in the workplace. Seuss’s workers are all co-owners and co-exploiters along with the Once-ler.

But when it came to portraying the process of producing Thneeds, Holly, Becky and David broke decisively with Dr. Seuss. In Seuss’s The Lorax, the Once-ler hires all his brothers, uncles, and aunts to become his work force. The choice allowed Seuss to ignore the hazards and divisions in the workplace. Seuss’s workers are all co-owners and co-exploiters along with the Once-ler.

My students decided instead to have their Once-ler draw his workers from the community:

And who sewed these damn useless

New Thneeds or whatever,

Did the rich Once-ler sew them?

Oh heavens, no, never.

The Once-ler had gotten

The Creatures of Lorne

To Make all these Thneeds

To wear and adorn…

The Once-ler thought Lorne Creatures were all merely slobs,

So he divvied them up, gave them all different jobs.

This was a smart thing for the Once-ler to do,

It made competition — it caused them to stew

The Bar-ba-loots, Swami-Swans and also the fish,

Had management jobs for which they would wish.

They had different jobs — some of them better

Some of them worse, and so the go-getter

Who looked out for himself, could get the good job,

Or so it was thought — it made them all snobs.

The Barbaloots, they got the best job of all

Upon you, said the Once-ler, the profits will fall.

They got nicer uniforms and better pays,

They had longer lunch hours, and shorter days.

The Swans got jobs that weren’t quite as good,

But they’d be paid more than the fish would.

The poor little Humming fish got least of all,

They were Nut and Bolt guys — their prestige was small.

And so it happened that all of these creatures

Forgot that the others had many nice features.

They started to think the same way

That the Once-ler had planned — they honored his say.

My students wanted to portray the work force realistically, as divided and exploited, rather than as one big happy family. Their Creatures of Lorne suffered both as workers and as residents of an increasingly polluted and deforested environment. In this way, Holly, David, and Becky wanted to suggest the possibility of alliances between workers and the larger community.

My students wanted to portray the work force realistically, as divided and exploited, rather than as one big happy family. Their Creatures of Lorne suffered both as workers and as residents of an increasingly polluted and deforested environment. In this way, Holly, David, and Becky wanted to suggest the possibility of alliances between workers and the larger community.

Dr. Seuss doesn’t even hint that readers might think in these terms. Instead, he muddies the analytical water by collapsing workers and owners into one class of environmental spoilers. Thus, workers are portrayed unambiguously as part of the problem — in fact, along with the Once-ler, as the problem. Perhaps unconsciously, Dr. Seuss adopts the stance of some environmentalists who see workers as enemies rather than as potential allies in a struggle for ecological sanity.

Organizing for Change

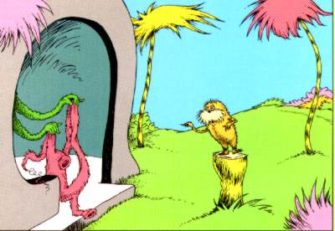

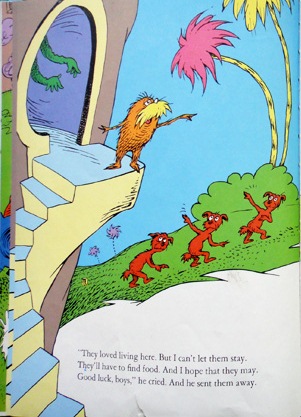

In Dr. Seuss’s story, the Lorax represents the only opposition the Once-ler faces. But instead of organizing groups like the Swomee-Swans and the Bar-ba-loots to fight for themselves and their environment, The Lorax becomes their advocate. He complains angrily to the Once-ler that because of his hacking down all the trees there is no longer enough Truffula Fruit. Although the Lorax models for children a stance of defiance in the face of injustice, he’s a dictator, albeit a benevolent one. As the environment deteriorates, he orders “his” Bar-ba-loots to leave. Later, he sends off “his” Swomee-Swans and then, because of all the Schloppity-Schlopp in the lake, sends off the Humming Fish. There is no suggestion that the Lorax might organize these creatures to stand together against the Once-ler. Instead, the creatures are portrayed as pathetic and powerless victims. Because there is no hint that the Lorax and friends could have chosen any other course, the message of Dr. Seuss is a cynical one. Failure was inevitable.

In Dr. Seuss’s story, the Lorax represents the only opposition the Once-ler faces. But instead of organizing groups like the Swomee-Swans and the Bar-ba-loots to fight for themselves and their environment, The Lorax becomes their advocate. He complains angrily to the Once-ler that because of his hacking down all the trees there is no longer enough Truffula Fruit. Although the Lorax models for children a stance of defiance in the face of injustice, he’s a dictator, albeit a benevolent one. As the environment deteriorates, he orders “his” Bar-ba-loots to leave. Later, he sends off “his” Swomee-Swans and then, because of all the Schloppity-Schlopp in the lake, sends off the Humming Fish. There is no suggestion that the Lorax might organize these creatures to stand together against the Once-ler. Instead, the creatures are portrayed as pathetic and powerless victims. Because there is no hint that the Lorax and friends could have chosen any other course, the message of Dr. Seuss is a cynical one. Failure was inevitable.

Holly, David, and Becky also introduced a Lorax-like character named Keith, but patterned him after the manipulative union organizer, Mac, in Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle.

With his deep- throated yell and his piercing blue eyes

He railed at the creatures and shouted “arise.”

He waved his big hands and stomped his big feet

And incited them all to stampede in the street…

Having little experience with self-governed thought,

The gullible creatures, protest they did not.

They followed him blindly, with fever and love,

Thus the Bar-ba-lotos, Swami-Swans, and of course the poor fish,

Looked up to this guy to fulfill their new wish.

They followed example, undertook the demand,

Of this weird guy named Keith, who came to command.

Although Keith and followers were able to topple the Once-ler’s rule, Keith quickly established a new hierarchy. In theory, The Creatures of Lorne now owned the productive resources of the society, but nothing had really changed:

The Truffula Trees continued to fall,

And the water — oh the water — got blackest of all.

And the fish developed really terrible diseases:

Ruskus and Fluskus and even the Fleasez.

Slowly, my students’ creatures begin to talk to one another about their conditions. They start to criticize their new leader. “The thing that makes him such a terrible bore is he’s just like that evil old Once-ler before.”

Unlike the creatures in The Lorax, my students’ creatures do not remain hapless victims. Nor do they arrive at some neat “solution.” Their story ends with the Swans and the fish and the Bar-ba-loots confronting their mutual prejudices. They come to agree that reversing the degradation in their working conditions and in the environment depends on their thinking and acting together — without relying on self-appointed leaders:

If you want me to tell you

That on that bright day

That those guys found the answer,

I’d be lying: No way!

We’re leaving this story unfinished

My friends,

Consider it more of a means

To an end.

For the thing that’s important

Is what that tiny fish said:

“If you want to be free,

You can never be led.”

In the student’s enthusiasm to distance themselves from the mix of paternalism and elitism embodied in Steinbeck’s Mac, or in a somewhat different form, in Dr. Seuss’s Lorax, they might be accused of advocating a kind of “ultrademocracy.” Obviously, there needs to be some kind of leadership in any struggle for justice. In discussion, students recognized the tension between democracy and leadership but insisted that ultimately their message was correct: “If you want to be free, you can never be led”— at least not in the way that Keith or the Lorax “led.”

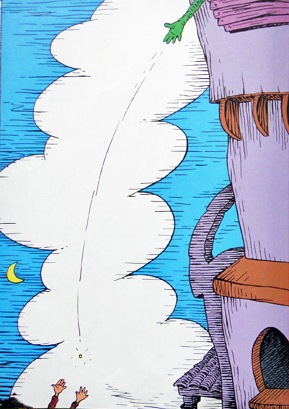

In contrast, Dr. Seuss concludes his tale with a speech by the Once-ler reminiscent in feeling of Scrooge’s conversion in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. In both instances, greedy owners come to see the error of their ways and, at least implicitly, renounce their earlier rapacious behavior and vow repentance. On the final page of The Lorax, the Once-ler is pictured throwing the last Truffula Seed to a little boy, and urging him to plant a new Truffula. The Once-ler implores the boy to care for the seed, to water it, and provide fresh air. The boy must protect the Truffula “from axes that hack.”

In contrast, Dr. Seuss concludes his tale with a speech by the Once-ler reminiscent in feeling of Scrooge’s conversion in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. In both instances, greedy owners come to see the error of their ways and, at least implicitly, renounce their earlier rapacious behavior and vow repentance. On the final page of The Lorax, the Once-ler is pictured throwing the last Truffula Seed to a little boy, and urging him to plant a new Truffula. The Once-ler implores the boy to care for the seed, to water it, and provide fresh air. The boy must protect the Truffula “from axes that hack.”

More than one message can be drawn from this ending. On the one hand, it’s a conclusion that calls on readers to be environmentally responsible: saving our rivers and forests is up to all of us. Urging people to protect the forests “from axes that hack” can even be read a demand to confront the “hackers.” However, the deliverer of this enlightenment is none other than the individual who was the original plunderer. And although the Once-ler’s conversion may seem hopeful, the misdirected political strategy that might logically flow from this presentation is that concerned citizens should appeal to the latent humanity and generosity of the environmental destroyers. If the Once-ler can change, why not all of them, the story appears to suggest; there is an environmentalist lurking in the heart of every lumber company and oil executive.

I prefer the democratic and grassroots approach proposed by Holly, David, and Becky: lasting change can only come from those victimized by an unjust system, not from those who benefit.

In many respects, I still think The Lorax is a delightful story and I certainly would not discourage teachers from using the book with students. But what is important is how we read with our students. As early as possible, we need to give students the tools to become social detectives, to develop a critical literacy that allows them read deep between the lines. From kindergarten through college, The Lorax may be as good a place to start as any.

Bill Bigelow (bill@rethinkingschools.org) is the curriculum editor for Rethinking Schools magazine and the co-director of the Zinn Education Project. This article first appeared in Rethinking Schools magazine and was reprinted in Rethinking Schools: An Agenda for Change (The New Press, 1995).

For more readings on critical literacy, check out Rethinking Popular Culture and Media from Rethinking Schools.

With respect, The Lorax was written for children as the target audience. Perhaps, Seuss had intended us adults to break up his story for literary interpretation. The message and dialog that goes with The Lorax are good, but just as Yertle the Turtle and The Butter Battle book are simplifications of tyranny and the Cold War, they were designed to open the discussion across various age groups.